Kathryn Jacob

King of the Lobby: The Life and Times of Sam Ward, Man-About-Washington in the Gilded Age

The Johns Hopkins University Press

240 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0801893971

King of the Lobby is about power, politics, money, and lobbying in Washington in the Gilded Age. It is about delicious food, fine wines, and good conversation and how one suave New Yorker, Sam Ward, combined all three to create a new type of lobbying—social lobbying—and reigned as “Rex Vestiari” for a decade. Scion of an honorable old family, brother of unassailably upright Julia Ward Howe, best friend of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, mathematician, linguist, California ‘49er, spendthrift who squandered several fortunes, Sam Ward was one of the most amazing men of an era crowded with larger-than-life personalities.

Lamentations that special interests, spending obscene amounts of money, strangle the voice of “the people”? More lobbyists than Corinthian columns in the halls of Congress? These sound familiar today in 2010, but the same stories filled the press and the Capitol building in the 1870s.

Lamentations that special interests, spending obscene amounts of money, strangle the voice of “the people”? More lobbyists than Corinthian columns in the halls of Congress? These sound familiar today in 2010, but the same stories filled the press and the Capitol building in the 1870s.

In the Gilded Age, when wave after wave of scandal uncovered congressmen who sold their votes and ruthless men who arrived in Washington with trunks full of cash with which to buy them, Sam Ward reigned unspotted as “King of the Lobby.” Not only that, he transformed what it meant to lobby. Bribes of railroad stock weren’t for him. “The King” traded in information exchanged at dinner parties, evenings that one guest gushed were “the climax of civilization.” At his table the outlines of a new, modern lobby, a lobby easily recognizable today, took shape. With the spotlight shining again on the lobby and while cries of abuses of power by special interests abound, exposing and understanding the roots of the modern lobby in the years after the Civil War gives context to the current debate.

Before the Capitol’s lobbies were even finished, special interest groups began lining up to exercise their First Amendment right “of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for redress of grievances.” How has the Constitutionally sanctioned lobby evolved in the intervening two centuries? Can wily lobbyists like Collis Huntington in the 1860s or Jack Abramoff in 2000 really be said to be seeking “redress of grievances”? Or is the nation now, as the press believed it was in the 1870s, going to hell in a hand-basket carried by lobbyists?

Themes important for examining Sam Ward’s life and the post-bellum lobby into the context of their times run throughout my career. My doctoral dissertation examined high society in Washington during the Gilded Age. As a historian for the U. S. Senate for more than a decade, I studied Congress and lobbying up close. As editor-in-chief of the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-1989 (GPO, 1989), I gained an understanding (and a trove of arcane details) of the lives of hundreds of former senators, some of whom got caught up in the cascade of scandals that washed over the two administrations of Ulysses S. Grant.

Research for my first book, Capital Elites, introduced me to Sam Ward, a key player at the three-way intersection of politics, power, and entertaining in the post-war years. My second book, Testament to Union, again took me into the thick of politics and lobbying, where I ran into the ubiquitous Sam once more.

In both of these books and in articles for American Heritage and Smithsonian on the Lizzie Borden ax murders, physician Clelia Mosher and her sex survey of American women, and sculptor Vinnie Ream, who unabashedly lobbied Congress for government commissions, I’ve woven biography together with social, cultural, and political history to create a colorful tapestry that not only examines a life but tells a bigger story about power, class, or gender–sometimes all three–and that’s what I’ve tried to do for Sam Ward and the post-Civil War lobby in King of the Lobby.

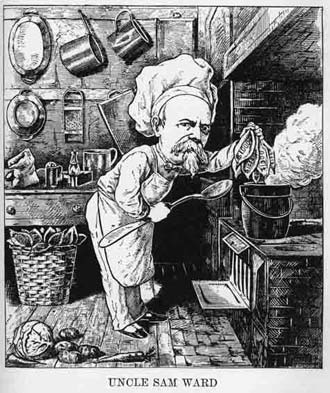

After lecturing the house Ways and Means Committee on the hazards of lobbying and the importance of dining well, Sam Ward told a parable about a clever cook, the king of Spain, and a meal with an unusual ingredient. In this newspaper cartoon, he cooks up a pot of $1,000 pigs’ ears himself. (New York Daily Graphic, December 20, 1876.)

By the early 1870s, Sam Ward was becoming known as the "King of the Lobby.” While there was a dash of hyperbole in the title, Sam loved it. To his sister Julia Ward Howe, he boasted that he was a sort of Figaro: “Tutti mie chiedono, tutti mi vogliono,…sono il factotum della citta. [Everybody calls me, everybody wants me, I am the factotum of the city.]”

But what exactly did Sam do for his clients? How did he, as he put it, “corral my congressional elephants”? In chapter four, pages 73 to 85, the key to Sam Ward’s success, what set him apart from other lobbyists, is revealed. Sam’s secret weapon was food.

Sam knew a recipe for success when he tasted it. Tinkering with the ingredients that had showed promise before the war, Sam used dinners and diplomacy as his preferred means to his ends. When Sam told Julia that “tutti mi vogliono,” what most of them really wanted was a seat at one of his dinners. Sam’s note about his “Congressional elephants” ended, “… call at the New York Hotel on Monday at 10 a.m., when you will find me at breakfast, and I will unfold to you my plan de campagne.” Sam’s special plan de campagne often began with pâté de campagne and champagne, with a client footing the bill.

Whether in consultation with a restaurant’s chef or his own, Sam took great care in composing every meal from his intimate lobby dinners to the grand banquets he orchestrated. The menu was, after all, he declared, “the plan of campaign, dependent upon the numbers of the enemy who will be reduced to capitulation by the projected banquet.” While Sam chose the menu, he deferred to his clients, whether the Secretary of the Treasury, European financiers, or American manufacturers, when drawing up the guest lists for his lobbying dinners. If their interests were financial, Sam would make sure that key members of the appropriate House and Senate committees received invitations. Mining and mineral rights? That was another group of players. Which members were alone in Washington and lonely? Who was most persuasive and who most easily persuaded? Who was leaning one way and who another? Who might like to sit next to whom? All of these factors went into the mix when selecting guests.

Once he had determined his tablemates, Sam concentrated on orchestrating the talk around the table. Good conversation was as essential as good food and wine, Sam believed, to the success of the evening: “It is with the succession of courses as with the sparkling wit that enlivens the repast. The airy nothings, the mots, the repartees and spontaneous flashes of wit and humor that crackle like so many electric sparks, are as unrecoverable as the lost patterns of a kaleidoscope.” Sam used stories from his variegated life like condiments at his table. He could salt dinner conversation with all sorts of tales: one of his favorites was about the time he improvised a weir to catch salmon in the hills of California.

The results of Sam’s great care in composing and conducting his dinners? “Ambrosial nights,” gushed one guest. An evening at Sam’s was, enthused another guest, “the climax of civilization.” “Nothing was ever served on Sam’s table,” claimed society reporter Emily Briggs, “that was half as delicious as himself.” He captivated Lillie de Lindencrone-Hegermann, the beautiful Boston-born wife of the Danish Minister. Sam Ward was, she wrote to her mother, the “diner-out par excellence…the King of the Lobby par preference….”

I’ve woven biography together with social, cultural, and political history to create a colorful tapestry that not only examines a life but tells a bigger story about power, class, or gender–sometimes all three.

The social lobby that Sam Ward perfected lived on. In the 1990s, hearings into lobby activities confirmed that the social lobby was alive and well in Washington. So well, so important, and so effective, in fact, that dinners and entertaining were specifically singled out for special rules in the 1995 Lobbying Disclosure Act that were tightened further in 2007. One can almost hear Sam sputter with indignation upon learning that neither members nor their aids can accept free meals from registered lobbyists.

Despite this closer scrutiny, the social lobby endures. It endures in part because of loopholes. There is the “toothpick rule” (food served on toothpicks, rather than on plates, does not constitute a meal) and the “reception exception” (members may still attend events where at least 25 people who are not congressmen and congresswomen are present). But the social lobby lives on primarily because, as Sam shrewdly recognized when he arrived in the capital in 1859, bringing people together over good food, wine, and conversation remains a fruitful way to break down animosities, make a point, and conduct business. What was a sure-fire plan de campagne for Sam is often a successful strategy still. Whenever lobbyists, clients, and congressmen come together at social occasions, even though they are more circumscribed, Sam is there, even though none present may know his name.

Sam almost certainly could slip into a well-appointed office at one of Washington’s top public relations firms on K Street and, in his well-cut suit, armed with statistics and his BlackBerry, make the rounds on Capitol Hill by day and, dressed in a dinner jacket with his diamond studs and sapphire ring, host and lobby at receptions, dinners, and benefits by night.

Sam would be happy to see that the social lobby, while just one of many avenues leading to influence in Washington, was still going strong and that entertaining remains an important opportunity for communication in the capital. As Arthur Schlesinger Jr., another keen observer of Washington, noted 100 years after Sam’s death, exaggerating just a bit as Sam was wont to do, “every close student of Washington knows half the essential business of government is still transacted in the evening…where the sternest purpose lurks under the highest frivolity.” Sam’s art was to guarantee that the men and women who enjoyed his ambrosial nights never focused on the purpose that lurked beneath his perfectly cooked poisson.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!