Dalia Judovitz

Drawing on Art: Duchamp and Company

University of Minnesota Press

288 pages, 8 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

ISBN 978 0816665303

The book’s title Drawing on art: Duchamp and Company refers to Marcel Duchamp’s literal defacement of the Mona Lisa image—and also to its figurative meaning, the treatment of art as an idea from which to draw inspiration.

This study shows how the idea of art became the critical fuel and springboard for new endeavors that challenge the meaning of art and of authorship. The deactivation of art’s visual mandate that emerged from the critique of the commodity and market forces, inaugurated by the readymades, opened up the possibility of questioning art’s premises and its social and cultural manifestations.

I argue that rather than negating or abandoning art, the readymades demonstrate the impossibility of defining it in the first place. They transform art into a resource for critical debate. To draw on art is to also to draw on other artists, which brings questions of creativity and artistic influence into play. The idea that the onlooker also “makes” the work of art activates the productive potential of the spectator’s consumption.

In addition to some analyses of Duchamp’s own works, the book provides detailed interpretations of works by other figures: those who proved influential on Duchamp’s thought and collaborated with him during the Dada and Surrealist period (notably Francis Picabia, Man Ray, and Salvador Dali), and those who later appropriated and redeployed these gestures by playing out their conceptual implications (Enrico Baj, Gordon Matta-Clark and Richard Wilson).

I suggest that all artistic production may be appropriative insofar as artists, in attempting to produce new works, necessarily draw on other works and other artists.

The idea that the onlooker also 'makes' the work of art overturns the myth of artistic genius undermining the idea of art as individual expression.

Drawing on Art: Duchamp and Company builds on the implications of my earlier work in Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit (1995). The focus is no longer on Duchamp alone but also on his Dada and Surrealist friends and sometime collaborators’ efforts to question the idea of art, creativity and authorship through their appeal to strategies of appropriation and collaboration.

The analysis proceeds along three major axes of inquiry. The first, involves various challenges to the visual fate and manifestation of painting and art in response to the forces of commodification, which are dealt with through the elaboration of conceptual strategies. The second seeks to redefine artistic creativity as a productive act that also entails spectatorship and hence notions of consumption. And the third focuses on the fact that artistic collaboration—understood as exchange, interplay, and appropriation of ideas—becomes paradigmatic of a new way of thinking about artistic production as an inter-active and inter-subjective endeavor.

The deactivation of the visual mandate of art that emerged from Duchamp’s and his Dada friends’ critique of the commodity and market forces opened up the possibility of questioning art’s founding premises and its social and cultural manifestations in the public sphere. Disillusioned with painting and art in general, Duchamp along with Picabia and Man Ray, and later with Dali, sought new strategies for challenging art’s vulnerability in the face of commercialization.

My book shows that while Duchamp with Man Ray, and later Dali, moved from the ocular to optics, seeking to activate a new understanding of the conceptual considerations that determine the production of visuality, Picabia along with Duchamp explored the potential of spectatorship as a force for taking on the pressures of consumption. Their critique of painting as a visual experience was extended to the film medium—to short circuit through conceptual considerations film’s advent as visual spectacle. For Duchamp and Dali, the game of chess became a privileged vehicle for figuring a new way of thinking about artistic making and authorship in the modality of play.

Another pivotal question I deal with is how artists inspire and influence each other in the production of new works.

The appropriation of Mona Lisa’s reproduction with the added mustache and goatee and its reissue under Duchamp’s signature transformed the passive spectator of Leonardo’s painting and/or consumer who purchased the painting’s reproduction into a producer who availed him or herself of a new way of making. Duchamp revealed the productive potential inherent in the spectator’s position as a consumer, thus undermining conventional artistic paradigms that privilege the act of the work’s production over its consumption.

I show that the idea that the onlooker also “makes” the work of art overturns the myth of artistic genius undermining the idea of art as individual expression. The invitation to partake in the creative process along with the author will implicate the spectator in a process of artistic making understood no longer in terms of self-expression, but rather as an act of critical responsibility.

Reversing conventional views of creativity, Drawing on Art suggests that all artistic production may be appropriative insofar as artists necessarily draw on other works, other artists, and the tradition in attempting to produce new works.

Last, this argument implies a redefinition of the artistic process as a collaborative partnership and activity. But how can this collaborative model be reconciled with Duchamp’s reluctance to formally associate with Cubism and later Dadaism and Surrealism, even as the latter two were wont to claim him?

Duchamp’s critique of artistic movements based on his rejection of artistic doctrine did not prevent him from selective participation in some group events, or from collaboration with fellow artists such as Picabia and Man Ray. These collaborative endeavors emerged and gained delineation during the Paris Dada period (1919-22), and they also include the Dada film experiments that followed it (1924-28), which marked the movement’s transition into Surrealism.

Moreover, collaborations of various kinds continued throughout, most notably his activities with Dali and the Surrealist group (especially as regards design of exhibition spaces and curatorial activities), and they persisted into the late 1960’s as we can see from his works with Baj, among others.

I claim that the full significance of such collaborations is to be found in the intellectual exchanges and influential play of ideas. And I propose that artists invariably draw on each other’s ideas and works and that the material conditions of production necessarily bring into play prior gestures and ideas.

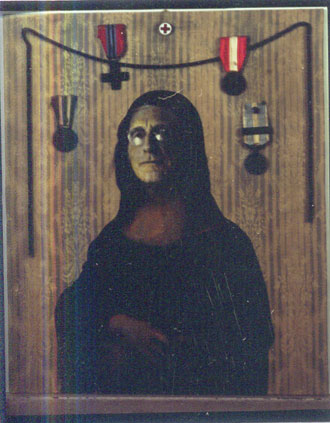

Enrico Baj. Homage to Marcel Duchamp. 1987. 55 x 46 cm. © Roberta Baj, 2008. (Image reproduced courtesy of Roberta Baj.)

The idea that the meaning of art may not be exhausted by its visual manifestations and the desire to look is examined as a response to the pressures of commodification implied in the emergence of public exhibition and market forces in the late 19th century.

I show that Duchamp’s readymades inaugurated the shift from the idea of capitalizing on the object’s visual appearance to exposing and playing on its modes of public presentation and display.

But what is art when “looks” no longer count? I argue that rather than enacting the negation and ultimate abandonment of painting, as most critics have contended, the readymades demonstrate the impossibility of defining art.

Coupling the ideas of art and anti-art in a dynamic play, their back and forth movement will mark their impasse (or “draw”) with painting, alluding to its postponement as visual expression and its continued promise as a conceptual enterprise.

It is in terms of this dynamic play that the readymades will emerge as paradigmatic of Duchamp’s later works, ranging across experiments in optics (windows, glass, and mirrors), in film, chess, and installation works. Conflating artistic and critical activities, these later works will conceptually question the meaning of art while outwitting the necessity for its physical manifestations. They will continue to attest to the impossibility of defining art even as they irrevocably demonstrate the necessity of moving beyond its visual impulse.

But what is art when 'looks' no longer count? I argue that rather than enacting the negation and ultimate abandonment of painting, as most critics have contended, the readymades demonstrate the impossibility of defining art

The impossibility of defining art once and for all may convince us of the viability—indeed, of the necessity—of no longer trying to do so.

If one accepts the legitimacy of the claim that not trying to define art is an acceptable premise, then this lack of a founding definition will not foreclose debate and dissent about its nature; it will invite and drive them.

What Duchamp (along with his Dada co-conspirators Picabia and Man Ray, and his Surrealist counterpart and sometime collaborator Dali) preserved and indeed reserved for postmodernism is an idea of art understood no longer as visual essence or expression but as locus of dissent and disparity of opinion. It is this modernist legacy that later collaborators such as Baj and/or postmodern appropriators such as Matta-Clark and Wilson drew upon and critically took to task.

The emphases of their works shifted away from the production of objects to the manipulation of the contexts that frame the idea of art in order to expose the institutional scaffolding that props up the possibility of meaning ascribed to works of art.

I argue that such an understanding of art no longer belongs to the realm of aesthetics alone, since it brings into play through its activation and engagement with spectatorship questions of responsibility and ethics.

Drawing on Art: Duchamp and Company shows how the idea of art, insofar as it relies on the works of the past not just as resource but as the springboard for the emergence of postmodernism, can become critical fuel for artistic impetus.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!