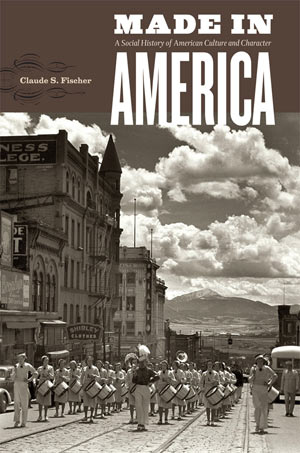

Made in America asks whether, how, and in what ways Americans of today are culturally and psychologically different from Americans of the past.The book reaches back to the nation’s colonial era and comes forward to 2010. Throughout our history, observers, both Americans and foreign visitors, tried to describe the special character of this new people in a new world. But what was fact and what was myth in those descriptions? What is fact and what is myth in the ways we understand our history today? Much turns out to be myth—say the notion that Americans today are more mobile and less religious than their ancestors, or that they are more “consumerist.”Made in America describes the material, social, and mental lives of average Americans from the earliest years through the industrial era to the present, focusing on the everyday experiences of everyday people, on how they survived, built families and communities, and came to understand themselves.Synthesizing decades of historical, psychological, and social research, Made in America reveals how growing security and wealth reinforced the combination of independence with commitment to community in the voluntarism that characterized Americans from the earliest years.Drawing on personal stories of many Americans from the past, the book describes how more people came to participate more freely and more fully in cultural and political life, thus broadening the category of “American.” At the same time, what it means to be American in culture and character has remained surprisingly consistent over the centuries.I mean this book to speak to such classic interpretations of America as The Lonely Crowd and Habits of the Heart. Yet, Made in America challenges many of their conclusions.