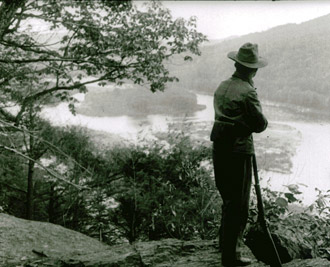

Italy in Early American Cinema traces the formal and ideological history of an aesthetic tradition, the Picturesque, from its original association with Italian landscapes to its deployment in early American cinema’s representation of the country’s distinct geographic and racial diversity. Thus the book touches upon formal conventions about national and racial difference that preceded the inception of moving pictures and even of photography, conventions which both producers and spectators, no matter their social or national background, knew and appreciated.This work began from the consideration that all too many studies of race in early American cinema tend to focus rather exclusively on individual groups. Reacting to this parcelization, I call attention to a sustained, transatlantic connection between how early American cinema as a whole represented racial difference and national identity and how, on both sides of the Atlantic, literature and image-making media had for centuries popularized romantic and entertaining representations of distant landscapes and populations.This pervasive aesthetic tradition, known as Picturesque, referred to both actual and painterly landscapes whose accidental or studied appearance turned their irregularity and roughness into appealing aesthetic effects. The Picturesque had emerged in conjunction with how European travelers, including writers and artists, romanticized Southern Italy’s ruin-dotted city views, pristine forests, erupting volcanoes, and quaint populations. Over time, the Picturesque’s reconciling arrangements came to imbue not only burgeoning tourist and image-making industries promoting the pleasing representation of distant places and populations, but also modern nations’ idealized representations of their own striking natural views and marginal dwellers.After showing the international popularity of Italian picturesque representations, I discuss how the Picturesque became the first American aesthetic. In the United States, the Picturesque popularized charming depictions of natural and urban sceneries, from the Hudson River Valley and the Wild West to the nation’s largest metropolis, New York City. Through pleasant arrangements of landscapes and man-made presences, the Picturesque offered something that American tourist and railway boosters as well as artists, writers, and filmmakers deeply needed: a familiar design to sort through, exoticize, and thus domesticate the wilderness of American natural and social landscapes—from the Niagara Falls and the immense Western forests to the Lower East Side.Early American cinema was keenly sensitive to the Picturesque. Western, gangster, and melodramatic films, as well as travelogues, deployed the picturesque tradition of “agreeable pictures” to idealize—to Americanize, that is—“agreeable races,” from noble, yet vanishing Native Americans to Italians, the Picturesque’s original subjects. Ultimately, however, the Picturesque identified a pleasing, manageable, and assimilable alterity that was not for everybody: to be picturesque or “colorful” implied not to be “colored.”