Jonathan Walker

Pistols! Treason! Murder! The Rise and Fall of a Master Spy

The Johns Hopkins University Press

288 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0801893704

Pistols! Treason! Murder! describes the short, disturbing and unprecedented career of a Venetian spy, Gerolamo Vano, who was executed for perjury in 1622.

In the years immediately preceding his death, Vano wrote hundreds of surveillance reports, based on material compiled from a revolving cast of suborned informants. Vano submitted these reports to his nominal employers, the Venetian Inquisitors of State, who were dedicated to protecting state secrets—that is, to counter-intelligence in modern parlance. Vano’s targets were the embassies of powers then hostile to the independent Venetian republic, principally Spain and her Hapsburg allies. In working against these targets, Vano was one of a number of competing suppliers in what we might describe as a deregulated free market of information (indeed, a black market); one whose invisible operation on capitalist principles was unique in the guild economy of early seventeenth-century Venice.

The Inquisitors of State did not directly employ informers (although they could directly reward them); rather, they delegated this task to independent intermediaries like Vano, whose reports are distinctive among those submitted by his contemporaries for their professional focus. They are also crudely melodramatic and obviously mendacious, even if it is virtually impossible to catch Vano outright in any specific lie. Nonetheless, these reports resulted in the arrest, imprisonment and/or execution of several of Vano’s protagonists. But since the Inquisitors’ final statement on the matter was to execute Vano for perjury, his reports clearly present unique interpretive problems.

Pistols! Treason! Murder! is therefore about Vano as a storyteller, but it is also more generally about the role of stories in historical analysis. To do justice to Vano, it was necessary to experiment with several devices that have no direct equivalent in his surveillance reports, but that illuminate them by analogy, such as original illustrations drawn in the style of seventeenth-century woodcuts and a dialogue between myself and two other historians.

The major issue for seventeenth-century Venetians was not how to assert their individuality so much as how to reconcile competing claims on their loyalties. Nonetheless, this problem itself contributed to the 'birth of the individual.' People became aware of who they were not only by meditating on their own uniqueness, but by outwardly pretending to be someone they were not.

Venice in the 1610s and 1620s was the first European state to undertake systematic surveillance of private individuals, and to entrust the supervision of such surveillance to a permanent committee, the Inquisitors of State. Vano was one of the first people involved in this process to fashion himself as a professional spy—as Venice’s “General of Spies,” no less. Thus Vano’s career is not only an invitation to rethink historical storytelling, but an invitation to rethink the place of the spy within the genealogy of modernity.

Jacob Burckhardt, in his groundbreaking study The Civilization of the Renaissance, first published in 1860, concentrated on architects, artists and the princely despots who transformed political life by treating the state as if it were also a work of art, which meant that it could be remade and transformed according to its ruler’s wishes. Since Burckhardt wrote his book, modernity has lost much of its shine. The alienated, protean figure of the spy, whose existence is defined by bad faith and duplicity, seems more representative of contemporary disillusionment than Burckhardt’s heroic geniuses do. Baroque cynicism has replaced sunny Renaissance optimism.

The major issue for seventeenth-century Venetians was not how to assert their individuality so much as how to reconcile competing claims on their loyalties. Nonetheless, this problem itself contributed to the “birth of the individual.” People became aware of who they were not only by meditating on their own uniqueness, but by outwardly pretending to be someone they were not. They began to define identity in terms of what separated them from other people. The origins of this way of thinking lie in the careers of men like Vano as well as those of courtiers and Burckhardt’s artists.

Gerolamo Vano was therefore a kind of performance artist; less idealised and more democratic than the traditional modernist hero, he lived in a compromised, complicated world, rather than existing on some higher, Olympian plane of Truth and Beauty. In his mind, as much as in that of the princely despot, the state became a work of art, but his art was ephemeral, improvised, and personal. He left no monuments to his genius except a pile of neglected, handwritten notes, but he explored the relationship between the private and the political in highly original ways. He was not above the moral obligations of mere mortals. Rather, he paid for the choices he made with his life—and those of others.

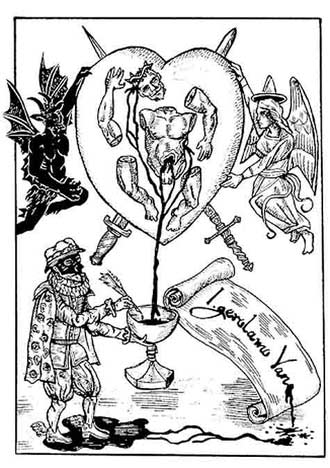

Pistols! Treason! Murder! contains numerous original illustrations, which I scripted and storyboarded, and which were created by Dan Hallett. The one reproduced here, titled The Wounds of Giulio Cazzari, accompanies the title chapter. It depicts in allegorical form the assassination of Giulio Cazzari, one of Vano’s numerous victims.

Vano’s costume here is taken in part from that of the figure of “The Spy” in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia, a ubiquitous visual source book of the period. Note the cloak of eyes and ears, and the winged boots of Hermes, messenger of the gods, who was also patron of “revelation, commerce, communication and thieving” (Vano’s activities fell under all four categories).

The cup is filled with ink, but obviously alludes to the Holy Grail, while the imagery as a whole also suggests the iconography of the wounds and sacred heart of Christ. However, in the context of the book, there is a more explicit reference to a passage from an earlier chapter, “Idiolect,” in which Vano’s words, read aloud, “taste like red wine—or, to be more precise, bad red wine: acidic, furring the tongue, lips and teeth; intoxicating, yet also prone to induce sore eyes and jabbing headaches. The more of them you speak, the more they numb the mouth and brain, and induce slurring.”

Intoxication as a response to Vano’s words is a recurrent theme in the book, underlined elsewhere by another image in which I am shown drinking from the same cup into which Vano dips his pen here.

In the image above, intoxication is further associated with a kind of knowledge based on vicarious participation in historical events through exemplary re-enactment, that is with the stigmata, and with holy communion, in which a Christian devotee respectively receives the wounds of Christ, or ingests the blood of Christ. But here the sacred meaning is violently profaned. The secular grail that Vano holds aloft is therefore the elusive, unattainable goal of every historian’s quest: direct, unmediated access to the past. Finally, the disassembled corpse of Giulio Cazzari, the victim whose remains lie within the heart at the image’s apex, also alludes to the fragmentary nature of the sources recounting his death, which cannot be stitched together into a single, coherent narrative.

To be absolutely clear, this image makes no claim to be a literal depiction of anything. Although it is composed of elements adapted from early modern sources, I have no idea what Vano or Cazzari looked like or wore. And while Cazzari certainly was assassinated as a result of Vano’s reports on his activities, his dead body was not in fact dismembered. This image is therefore a kind of diagram, one mapping arguments and elaborating subtexts rather than describing events.

None of the ideas outlined in the discussion above are expressed directly in the text of the book. Such explanation would be redundant: the argument is all there in the illustration itself, and in its implied relation to other elements of the presentation, both visual and linguistic. So another of my arguments is, in effect, that we should take images seriously as independent vehicles for complex and abstract ideas.

Although this image is composed of elements adapted from early modern sources, I have no idea what Vano or Cazzari looked like or wore. And while Cazzari certainly was assassinated as a result of Vano’s reports on his activities, his dead body was not in fact dismembered. This image is therefore a kind of diagram, one mapping arguments and elaborating subtexts rather than describing events.

The conventions of professional historiography require abstraction, restraint, and decorum. Gerolamo Vano has no place within this regime, just as he had no place within the official rhetoric of political culture in seventeenth-century Venice. Vano demands instead exemplification, excess, and vulgarity. By exemplification, I mean that the way the story is told becomes a commentary on its subject, so that the form of the presentation itself embodies the argument. By excess, I mean that the presentation borrows Vano’s contagious enthusiasm, and echoes his violent disregard of all conventional pieties. By vulgarity, I mean a willingness to cross the divide between high and low culture, a divide that Vano also ignored. Hence, allegorical comic strips; hence, three exclamation marks in the title; etc., etc.

Several reviewers have responded to this approach with bafflement or irritation. Why can’t I just write a normal history book? The point is that the normal protocols of interpretation do not work when applied to Vano’s reports; nor will his fragmentary story fit within the bounds of a conventional narrative.

In response to these difficulties, we might simply conclude that the endeavour is impossible, and choose another subject. But an alternative course of action is to try to make the difficulties a compelling part of the story. When words fail, silence is not the only alternative. We can use pictures instead, or invite the participation of other voices through dialogue, or foreground gaps in the record by jump-cutting.

Pistols! Treason! Murder! is not, therefore, just the story of Gerolamo Vano, a Venetian spy, although Vano is certainly a uniquely interesting individual; nor is it simply an attempt to place Vano within a particular historical context, although that context is certainly of unique importance. It is also an attempt to test the limits of historical representation, and to ask what happens if we deliberately transgress those limits.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!