Robert E. Sullivan

Macaulay: The Tragedy of Power

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

624 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0674036246

Macaulay: The Tragedy of Power is a cultural biography of Thomas Babington, Lord Macaulay (1800-1859). The eclipse of his reputation may suggest that there’s nothing deader than a dead empire. Once as inescapable as England’s, which he helped to build and popularize, his name is now known only to liberal arts graduates of a certain age and to students of nineteenth-century culture.

But do great empires ever entirely die? Today Macaulay’s legacy flourishes in South Asia, where he detested living but relished power. When you hear the voice of a fluent English-speaker in a call center in what was recently Bangalore (Bengalooru), consider that in 1835 Macaulay was instrumental in launching English as the subcontinent’s shared language. If this weren’t enough, the penal code for India that he almost singlehandedly drafted remains in force there and elsewhere in the late British Empire.

Macaulay was also long a cultural power wherever English was spoken or read. In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt recommended his History of England to American historians as a model, and TR wrote the kind of history that he preached. The tenacious veneration of Macaulay as a sage is as telling about the underside of the history of the English-speaking peoples during the last two centuries as it is about his prodigious talents.

Like every successful imperialist, Macaulay possessed a myopic emotional sensibility: a highly selective, narrow—even exclusive—awareness of other human beings. His father Zachary was a heroic evangelical abolitionist and an ineptly domineering parent—imagine Charles Dickens’s Mrs. Jellyby, global in her charity but heedless at home, but Mrs. Jellyby with sharp teeth.

Zachary’s heedless parenting taught his first-born to view human relations as essentially a business of domination and submission, always regulated by the steely calculation of self-interest. He was an emotional cripple. Honors, wealth, and power intensified his self-absorption. Only a handful of people were completely real to him. All the rest were, in the end, “not necessary” and thus expendable. Macaulay’s life became a tragedy: a great man devastated by a flaw.

Like every successful imperialist, Macaulay possessed a myopic emotional sensibility: a highly selective, narrow—even exclusive—awareness of other human beings.

The interaction of modern religion and its surrogates interests me. It’s often misleadingly called “belief versus unbelief.” In fact, all of us believe a lot. For centuries intelligent people, both religious and non-religious, have been engaged in a conversation, sometimes become a mindless shouting match. Seven years ago I was trying to write a probably unwriteable book on how, between ca. 1800 and 1950, a confidently modern, religiously emancipated elite derived spiritual sustenance from the ancient Greek and Latin classics.

Because Macaulay was both an omnivorous classicist and an eminent post-Christian, I began reading his published works and letters in chronological order. A few pages into Sir William Temple (1838), much concerned with the classical mania of that seventeenth-century English diplomat and writer, he seems to digress on Oliver Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland in 1649. Macaulay misrepresents Cromwell’s slaughter of thousands of “aboriginal Irish” in wartime as a farsighted program of empire-building—regrettably never completed—and a model for later progressive, modernizing projects. Macaulay declares that, “it is in truth more merciful to extirpate a hundred thousand human beings at once, and to fill the void with a well-governed population, than to misgovern millions through a long succession of generations.”

The sentence was a thunder stroke. Far from being edgy satire or a lapse, Lord Macaulay’s endorsement of what I call “civilizing slaughter”—“genocide” and “ethnic cleansing” are twentieth-century words—was occasionally rephrased but never suppressed. His essay on Temple remained in print until 1974, and you can now read it as a Google Book. Nobody seems to have commented on its “luminous and terrifying” vision—perhaps even cared—until the 1990s, and then only in a couple of confused footnotes. Instead Macaulay was widely praised for championing “the rights of Jews, Roman Catholics, and Negroes.”

Macaulay explores what in his life and our culture made him both the first responsible European publicly to advocate civilizing slaughter and an icon into the second half of the twentieth century. The vast silence about his sinister prophecy during his lifetime and beyond resulted from indifference, acquiescence, and sometimes complicity.

Lord Macaulay dared to write and say publicly what many other respectable people in Europe and North America had previously dared only think or whisper. He was a cool realist, who understood that political power depends on violence or the threat of violence, inferred that in politics might and right are much the same thing, and upheld the English empire as the progressive engine of modern civilization.

By 1871 Charles Darwin, a humane man and fairly consistent liberal, restated what Macaulay helped to make conventional imperial wisdom as a law of evolutionary biology: “Extinction follows chiefly from the competition of tribe with tribe, and race with race . . . When civilized nations come into contact with barbarians the struggle is short, except where a deadly climate gives its aid to the native race.”

Until the day before yesterday and from both the Left and the Right, various luminaries have envisioned schemes of mass slaughter and the slaughter itself as driving the forward march of modern civilization. Friedrich Engels, Marx’s adjunct, was not alone in viewing history as “about the most cruel of all goddesses,” leading “her triumphal car over heaps of corpses.”

The introduction, the envoi, and two pictures may be worth several thousand words.

The introduction surveys the book, and the envoi traces Macaulay’s impact to our times.

The book’s dust jacket reproduces Edward Matthew Ward’s 1853 portrait of Macaulay in the National Portrait Gallery in London, an institution that Macaulay helped to invent. He sits comfortably in a well-appointed study, but the stacks of manuscripts on his writing table challenge the order of his bookshelves. Half of his face is shadowed. He is alone. Intimating that there’s more to Macaulay than meets the eye, Ward’s artistry captures the man’s mysterious doubleness, the need to conform and be accepted, as well as to simulate and dissimulate, which marked him from adolescence and helped to enable his success. It also captures Macaulay’s self-absorbed detachment from other people.

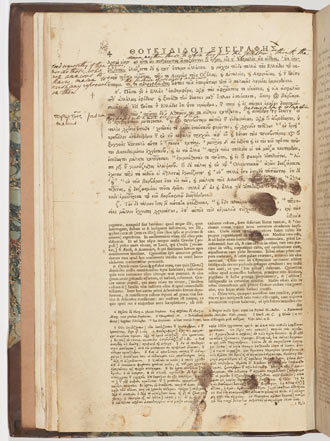

Facing pages of Macaulay’s annotated copy of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War in Greek, preserved in a former country home of his distinguished collaterals, fill pages 142-143. During his Indian years Macaulay passed “the three or four hours before breakfast in reading Greek and Latin” and kept at it while being shaved. His numerous annotations in English, Latin, and Greek evidence his immersion in antiquity. The bloodstained, much-fingered pages testify to his impervious concentration rather than a shaky barber. Macaulay was a genius who lived mainly in his own mind.

Should a reader be intrigued and her bookstore cappuccino still warm, she might scan pages 449-468 in the last chapter. It’s called “A Broken Heart.” The words are Macaulay’s and capture both his long-term depression and the cardiovascular disease that killed him. He was teary and food-addicted. Neither a psychiatrist nor a psychologist, I am unwilling to inflict incompetent theories on someone long dead. And so I let Lord Macaulay speak for himself at great length. My aim is to use his own record of himself, primarily in his letters and manuscript diaries to try to capture his sensibility, the patterns in his recorded perceptions and interactions that reveal how he saw and negotiated the world.

Lord Macaulay dared to write and say publicly what many other respectable people in Europe and North America had previously dared only think or whisper. He was a cool realist, who understood that political power depends on violence or the threat of violence, inferred that in politics might and right are much the same thing.

Those pages are subtitled “The Sensibility of Power.” The condition and its consequences are inescapable human realities—I believe in original sin. At the end of 2008 while finishing the manuscript, I read Richard Holbrooke’s review of Gordon Goldstein’s Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and the Path to War in Vietnam. Long ago in Saigon, Holbrooke, now our special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, encountered Bundy. After serving as a uniformed noncombatant during World War II, Bundy became self-confidently one of “the best and the brightest” and then an architect of the Vietnam War, hopelessly but unwittingly out of his depth. Holbrooke still blanched at Bundy’s encompassing emotional “detachment.” It fed on the deficient self-knowledge that enabled him to reduce groups and individuals to bloodless abstractions. To some extent, so must everyone who wields power over life and death. Imbued with the sensibility of power and brilliance, Macaulay was nearly complete and potentially lethal in his detachment.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!