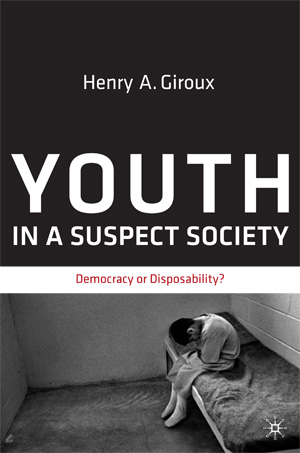

In many ways, Youth in a Suspect Society is motivated by a sense of outrage and a sense of hope.While youth have always represented an ambiguous category, they have within the last thirty years been under assault in unprecedented ways. The book identifies a number of forces—including unfettered free-market ideology, a dehumanizing mode of consumerism, the rise of the racially skewed punishing state, and the attack on public and higher education—that have come together to pose a threat to young people. The combined threat of these forces is so extreme it can be accurately described as a “war on youth.” Since the late 1970s, young people have been transformed from a generation that embodied hope for the future to a generation of suspects in a society destroyed by the merging of a market-driven corporate state and the increasingly powerful punishing state. Central to this claim is the idea that the current generation of young people is no longer viewed as an important social investment or as a marker for the state of democracy and the moral life of the nation. Youth are now under assault by a number of forces, the most widespread and insidious of which are market-driven forces and pedagogies of consumption that increasingly penetrate every aspect of young people’s lives so as both to commodify them and to undercut their possibilities for critical thought, civic responsibility, and engaged citizenship.Moreover, as the welfare state has been gradually dismantled, youth have also become the objects of a more direct and damaging assault waged on a number of political, economic, and cultural fronts. Young people are increasingly subject to modes of governance, education, punishment, and control largely modeled after prisons and the dictates of a youth-crime-governing complex that increasingly subjects them to harsh discipline, while criminalizing more and more aspects of their behavior. From the schools to the streets, poor minority youth are subject to modes of control based on crude and degrading forms of punishment, including random drug tests, locker searches, racial targeting, surveillance, and zero tolerance laws.Youth in a Suspect Society argues that only by understanding the unique merging of casino capitalism and the punishing state—and the reach of this new social formation in shaping everyday life—does it become possible to grasp the contours of a new historical period in which a war is being waged against youth.The book also considers the role that academics and institutions of higher education may take in addressing the crisis of youth and its relationship to politics and critical education. A particular focus is on how intellectuals and other cultural workers can intervene to stop this assault on youth through a politics that both rejects the equation of capitalism and democracy and connects youth to a future that embodies the promises of an aspiring democracy.