Jennifer Barker

The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience

University of California Press

208pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0520258426

In Michel Gondry’s The Science of Sleep (2006), Gael GarcÃa Bernal plays a frustrated artist with a penchant for quirky handmade objects and stop-motion animation who falls in love with an artsy woman. He explains, “I love her because she makes things with her hands. It’s as if her synapses were married directly to her fingers. Like this,” he says, staring at his own waggling fingers in amazement, “in this way.”

That line perfectly describes the spectator—not just of this film but also of moving pictures in general. I argue that synapses and fingers are married (as are mind and body, and vision and touch more generally) in the experience of cinema. I also argue that to think, to speak, to feel, to love, to perceive the world and to express one’s perception of that world are not solely cognitive or emotional acts taken up by viewers and films, but always already embodied ones that are enabled, inflected, and shaped by an intimate, tactile engagement with and orientation toward others—things, bodies, objects, subjects—in the world. If these things are married in the experience of cinema, then this book describes exactly how so: “like this, in this way.”

That the film experience is a tactile one is without doubt; one need only chat up one’s fellow audience members to hear an action film described as a “visceral rush,” or an art film described as “lush” or “sensuous.” But how does one reconcile sensuous film experience with film theory? My answer was to design a book that is itself a tactile experience. I employ a descriptive vocabulary and method, infused with the sensuousness of the everyday, embodied film experience, in a study organized not around historical periods, genres, or modes of production, but around bodily dimensions, sensations, rhythms, and gestures.

Throughout the project, I describe “touch” in a way that extends beyond the fingers and the skin. The book’s three central chapters explore three locales that I argue are lived both humanly and cinematically: the skin, the musculature, and the viscera. These categories guide us through a complicated terrain, but their boundaries are pliable and permeable. Sensations and behaviors constantly bleed, vibrate, dissolve, spread, cut, or muscle their way from one dimension into the next.

I explore these dimensions of tactility through a series of brief but detailed readings of specific films, which I call “textural” (rather than “textual”) analyses. I cover a wide range of genres, nations, and directors, juxtaposed in unpredictable ways—Buster Keaton and Wile E. Coyote share the space of a few pages, as do Eraserhead and Toy Story—that elicit underlying haptic, muscular, and visceral patterns shared by film and viewer and that offer a useful approach for the study of other film experiences.

I develop the notion of 'viscera' as a means of discussing both the resonance and the tension between the internal rhythms of the human body and those of the film’s body.

The Tactile Eye emerged as a response to my own craving for what anthropologist Paul Stoller calls “sensuous scholarship.” I was inspired by certain film and art history scholarship in the mid-1990s that took up an interest in the non-visual senses, including work by Vivian Sobchack, Tom Gunning, Giuliana Bruno, Laura Marks, and Elena del RÃo. These writers, alongside others working in philosophy and anthropology, informed my own thinking about phenomenological film theory and issues of embodiment.

The book takes up two concepts in particular: “body genres” and the “film’s body.” In writing about horror, melodrama, and pornography, Linda Williams defined as “body genres” those genres in which viewers identify with certain characters’ embodied on-screen behavior in complex ways. The Tactile Eye argues that all genres are “body genres” in the sense that viewers identify not solely with characters’ bodies but also, and more importantly, with films’ bodies.

I also expand on the notion of the “film’s body,” developed substantially by Sobchack. When we watch a film, we’re seeing the film seeing; we see its own (if humanly enabled) process of perception and expression unfolding in space and time. Camera movements, fluctuations in sound, and degrees of intensity, attention, distraction, etc.—these are embodied behaviors and/or attitudes of the film’s own lived body, which is unified in time and space and which performs its own perception (of the world) and expression (to the world) in embodied ways that are muscular, tactile, and distinctly cinematic.

I’m especially intrigued by the carnal resonance between the film’s body and the viewer’s. Watching a film, we are certainly not in the film, but we are not entirely outside it, either. We exist and move and feel in that space of contact where our surfaces mingle and our musculatures entangle. This sense of fleshy, muscular, visceral contact seriously undermines the rigidity of the opposition between viewer and film, inviting us to think of them as intimately related but not identical, caught up in a relationship of reciprocity and reversibility, rather than as subject and object positioned on opposite sides of the screen.

The Tactile Eye broadens the definition of “touch” in a literal but imaginative way, to include not only haptic but also muscular and visceral modes of touch that shape the encounter between films and viewers. For example, the film has a skin in the sense that it has a surface that is at once porous—impressionable, prone to contagion, and yet capable of transmitting its own qualities to others —and firm—a boundary, a container, and a shield against the world but also a source of contact with it. The press of skin against skin, both within the film and between film and viewer, can provoke an intersubjectivity that entails pleasure, horror, and many things in between.

Haptics are the most immediately apparent form of touch, and the only one for which there are precedents in film scholarship, but cinematic tactility is more than skin deep. Indeed, if the film has a body, it must have body language, and for this I devised the category “musculature”: films and viewers express themselves through movement, comportment, gesture, and the arrangement of the body in space. Here I turn to perceptual psychology to discuss proprioception, psychic blindness, phantom limbs, and the notion of embodied empathy.

Drawing upon medical phenomenology, I develop the notion of “viscera” as a means of discussing both the resonance and the tension between the internal rhythms of the human body and those of the film’s body. I describe the way film and viewer suffuse one another with their respective textures, temperatures, intensities, rhythms, gestures, and contours in a way that encompasses surface, middle, and depth. The embodiment of emotion, an idea that permeates the entire book, comes to the forefront here.

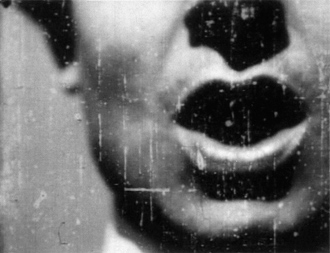

The full-bodied, mutual suffusion of film and viewer is illustrated graphically and literally by The Big Swallow (James Williamson, 1901). The film begins with a medium-long shot of a gentleman gesturing angrily and shouting (silently, of course) at the camera, presumably because he does not want to be photographed. He moves aggressively closer and closer to the camera until his wide-open mouth blocks the view entirely, seeming to swallow up the camera. An invisible cut to a black background creates a void, into which the flailing cinematographer and his old-fashioned camera pitch forward and disappear. Another invisible cut brings us back to the gentleman’s open mouth, and he retreats from the camera, chewing and laughing at his clever triumph over the cinematographer and the apparatus.

The film’s provocative premise suggests that while cinema has an astonishing ability to “draw us in” to its spectacle, the positions of film subject, viewer, and filmmaker are tenuous at best in this exchange. The film appears to engulf not only the cinematographer and the apparatus but also, by extension, the viewer. The cinematographer is at first unseen, as the man being photographed walks toward the camera, but as the gentleman opens his mouth, the cameraman tumbles with his equipment into the gaping mouth of what had been, just a moment before, the filmed image of the gentleman.

Because of the cinematographer’s absence from the first image, we the viewers share his position; we initially view the filmed man from the same position that the cinematographer does. Thus, when the cinematographer is swallowed up, so must we be. But we are left alive to see the swallowing up, now outside the relationship we’d been part of a moment before, and in the final shot the gentleman grins smugly at the camera despite the fact that he has just been seen to devour said camera in a single bite. The film turns inside and outside itself and back again, swallowing itself up and spiting itself back out, in the space of a few seconds.

The Big Swallow forces the question, where are we in this picture? The ambiguity of Williamson’s film suggests the tactile, corporeal, reversible contact between film and spectator, who embrace or even ingest one other—in both directions—and yet do not disappear into one another entirely. The Big Swallow depicts quite literally and imaginatively the intimate and tactile crossover of the inside and the outside, of the subject and the object of this tactile vision. The film’s final return to the smiling man at the end of the film places the emphasis squarely on the film experience taken as a whole, rather than on subject or object, viewer or viewed. That ambivalent but sensuous tactile contact between film and viewer moves all the way through the skin, musculature, and viscera, so that we are inside the film and outside it at the same time.

That ambivalent but sensuous tactile contact between film and viewer moves all the way through the skin, musculature, and viscera, so that we are inside the film and outside it at the same time.

Film theory and criticism have often described the meeting place of film and viewer as a mirror, a screen, a window, or a door. No one metaphor sticks, perhaps for two reasons. First, the “stuff” of the contact between film and viewer is too permeable and flexible to be described in quite these rigid terms. Second, what keeps us separate from the film isn’t a “thing” at all, but our bodies’ own surfaces and contours.

Philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s notion of “flesh” (which differs dramatically from literal skin) may be a better metaphor. The material contact between viewer and viewed is less a hard edge or a solid barrier placed between us—a mirror, a door—than a liminal space in which film and viewer can emerge as co-constituted, individualized, but related, embodied entities.

The notion of “flesh” encourages us to see the connection between film and viewer not only as a tactile “interface,” but perhaps even further as a mutual immersion. More than that, it may encourage us toward a new style of historiography, theory, and criticism. Indeed, I am convinced that the (re)invention of moving image studies and the mutual absorption of film and viewer are closely related.

Insightful critical writing about cinema requires a passionate, sensuous approach that respects the passionate, sensuous, and specifically tactile engagement between viewers and films. It’s my hope that The Tactile Eye helps to encourage this embrace of sensual experience not only for the purposes of description, but also as an integral tool for film history and theory.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!