Deborah Cohen

Household Gods: The British and Their Possessions

Yale University Press

336 pages, 9 x 8 inches

ISBN 978 0300112139

Household Gods is a history of the British love-affair with the domestic interior from the age of mass manufacture to modernism. In no other country was domesticity so celebrated and studiously cultivated. Money fed house-pride: between the mid-nineteenth century and the Second World War, Britons enjoyed the highest average standard of living in Europe.

Though we have in so many ways inherited the world the Victorians made, we know surprisingly little about how they responded to their unprecedented prosperity. How did the legendarily duty-bound middle classes of the nineteenth century reconcile moral good with material abundance? How can we explain their apparently insatiable, and to our eyes quixotic, demand for things? Why, to put it simply, did they stuff their houses full of objects? When—and why—did people first begin to believe, as many of us do, that our homes reflect our personalities?

In Household Gods, I argue that our modern consumer society has its roots in early nineteenth-century religious fervor. Over the course of the Victorian era, consumerism shed the taint of sin to become the pre-eminent means for the expression of individuality. The manner by which the Victorians reconciled their newfound prosperity with moral good is a crucial step in the making of modern materialism.

Unlike previous histories of British interiors, which have concentrated on opulent rooms or avant-garde developments, this book delves into the realm of middle-class self-fashioning—what critics have often dismissed as bad taste. Victorian luminaries such as critic John Ruskin and designer William Morris had less influence than we have assumed. I draw upon a wealth of untapped sources to explore the much broader set of forces that shaped consumer desires.

Religious and moral qualms figure in this story, as do anxieties about the regard of neighbors and friends. The temptations of shopping vie with the constraints of the pocketbook; the urge to differentiate oneself from others confronts, time and again, the desire to fit in. In a wide-ranging account that ventures from musty antique shops to London’s luxurious furnishing emporia, from suburban semi-detached houses to aestheticism’s leading lights, from married men who fretted about the appearance of mantelpieces to women who embraced home decoration as a feminist cause, Household Gods asks how people made and re-made themselves in a country in which the question was no longer merely “who are you” but “what have you.”

The manner by which the Victorians reconciled their newfound prosperity with moral good is a crucial step in the making of modern materialism.

My book began as an inquiry into the origins of consumer demand. In the past two decades, economic historians have established that consumer demand provided an important catalyst for industrialization. However, we still don’t know very much about the reasons why people wanted things. Pioneering scholarship on the so-called “consumer revolution” assumed either that demand was an intrinsic, ever-present force, or that (following Thorstein Veblen) the middle classes spent money in order to ape their social betters. Research on the eighteenth century has done much to revise that narrative, pointing to, among other factors, a peculiarly modern form of hedonism. Nonetheless, the literature on consumer demand in the later period of mass manufacturing is far less well developed.

This omission is all the more striking given significance contemporary scholars accord to questions of demand from the 1840s through the 1930s. In the aftermath of the Great Exhibition, consumer taste (and, specifically, the public’s purportedly bad taste) became a matter of political and moral import in Britain. Design reformers—among them, Ruskin and Morris—sought to improve the quality of British goods by educating consumers, impressing upon them a preference for more tasteful products. Nonetheless, though the efforts of Ruskin and Morris have been exhaustively chronicled, we know almost nothing about their intended audience. We don’t know why people originally embraced the objects that reformers deplored, nor do we know how they responded to campaigns to improve their taste.

Understanding why people wanted things, especially in the case of the Victorians, requires us to grapple with the relationship between consumerism on the one hand, and religion and morality on the other. Religious strictures had, at various times in early modern European history, served to regulate consumption. Here I’m thinking of Simon Schama’s seventeenth-century Dutch, torn between the rigors of Calvinist discipline and the consumerist pleasures of the Golden Age, and of Max Weber’s capitalist entrepreneur, whose manner of life, as Weber famously described it, “was distinguished by a certain ascetic tendency.”

However agonizing these conflicts had been in the past, the nineteenth century put forth the issue with new urgency, for the Victorians were both richer and by some measurements also decidedly more religious than their eighteenth-century forebears. The evangelical revival of the early 19th century exercised a profound influence upon the British middle classes, who were, at least through the First World War, notoriously concerned with questions of faith and morals. But if Victorianism was synonymous with morality, the British were also, from the mid-nineteenth century on, the beneficiaries of Europe’s first real consumer boom. In Britain, the average per capita income rose from a marginal 25% above subsistence in 1850 to a comfortable 150% above subsistence in 1914.

With a few notable exceptions, the relation between religion and consumerism is an issue that has largely been ignored both in the literature on consumption and in scholarship about religion. But given the evangelical underpinnings of the Victorian period, what needs to be explained, at the outset, is the long co-existence of consumerist impulses and moral concerns—“the conciliation,” as George Eliot put it, of “piety and worldliness, the nothingness of this life and the desirability of cut glass.” How that reconciliation was achieved—and what its effects were—is the subject of Household Gods.

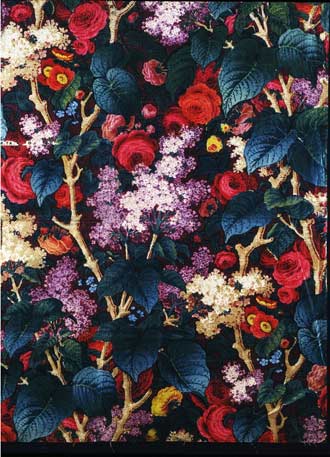

“Naturalistic” design. A furnishing fabric from 1850 of roller-printed and glazed cotton. The guest who lowered himself onto a sofa upholstered in this fabric had to fear that he might be impaled by a protruding twig.

The idea that interiors reveal personalities is such a truism of contemporary culture that it is difficult to imagine that it was not always so. While the well-to-do in previous eras lavished attention upon their mansions and country houses, such refurbishments more often attested to the dynastic ambitions of a family than the inner self of a particular lord or lady. If a few individuals in the Georgian period, such as the architect Sir John Soane, had aimed to transform their dwellings into monuments to their unique sensibilities, their efforts lay far beyond the imaginings or pocketbooks of the vast majority, whose concern was with comfort and propriety rather than romantic creativity.

What changed during the Victorian period was not just the purchasing power of middle-class Britons, but understandings of the self. In the mid-nineteenth century, Victorians had most often conceived of the self in terms of character, a religiously-inflected term that chiefly connoted a moral condition. A man’s character might be built through painstaking instruction and introspection; however, the path to improvement was tortuous.

By the 1890s, there was a new, seemingly secular way of thinking about the self, expressed in the concept of personality. If character was demonstrated by self-control and self-denial, a display of “personality” required individuality. Personality was malleable, creative, and complex; it accompanied a new, psychological conception of the mind. The home was the staging-ground for this new idea of personality.

In an increasingly heterogeneous middling stratum, a personality, expressed in a distinctive interior, became a necessary asset. The consumer boom—combined with this new confidence that possessions could communicate their owner’s individuality—made for a giddy period of acquisitive experimentation. Since furnishings made the person, no decorative scheme was off-limits, and “quaintness,” the quality of being out of the ordinary, was the desired effect. The spinster in Sussex who wallpapered her bedroom with black-bordered In Memoriam cards, the hostess who placed her guests in “spring,” “summer,” “autumn” and “winter” rooms according to their age belong to the human comedy of fashionably eccentric furnishing at the fin-de-siècle. So, too, do the young couples who decorated their drawing-rooms according to the prevailing fashions of pan-Asianism, with Indian-printed textiles cheek by jowl with fancy Japanese fans. Why not a Tess of the d’Urbervilles room, wondered one Thomas Hardy fan, envisioning a décor imbued with the “spirit of the West Country and the gloom of the book.”

Long the cradle of the family, the home became something more in the Edwardian period; the domestic interior literally helped to create the individual. C.S. Lewis was one of many who credited his boyhood home, considered apart from the members of his family, as “almost a major character in my story,” viewing himself as “a product” of its corridors and rooms. Yet the task of communicating one’s individuality would prove a far more perilous undertaking than middle-class furnishers had envisioned. What if one inadvertently broadcast the wrong message? When furnishings made the person, every decision could become a cause for regret.

Taste—no less than occupation, religion, or political affiliation—should be considered a crucial ingredient in the making of middle-class Britain.

In Britain, the locomotive of Victorian acquisitiveness was powered, in part, by an engine that ran on the unlikely fuel of spiritual striving. My book deals with the pentimento of militant Christianity, the shadowy imprint that remained even after damnation and eternal punishment were no longer preached from the pulpits. Edwardian critics liked to believe a world of difference existed between themselves and their more devout ancestors. But the distance between self-denial and self-expression was perhaps not as great as we might imagine. Most significantly, evangelicalism forced a concentration upon the self which was, in the generations that followed, modified, but not abandoned. While wealth, as Max Weber believed, may well have exercised a “secularizing influence,” that secularization was itself indelibly colored by religious antecedents.

Consumption served to define and to differentiate an extremely heterogeneous middle class. Taste—no less than occupation, religion, or political affiliation—should be considered a crucial ingredient in the making of middle-class Britain. Consumerism has re-oriented the social and political landscape. Writing in 1913, the historian G.M. Trevelyan saw a connection between the diffusion of consumer goods and the extension of the franchise. The right to vote, he observed, only came, “when the coats [that working men wore] were better.”

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!