Toby Talbot

The New Yorker Theater and Other Scenes from a Life at the Movies

Columbia University Press

400 pages, 8 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0231145664

This memoir is an inside account of the New Yorker Theater that my husband Dan and I opened on March 17, 1960. An Art Deco relief of Diana the Huntress and her hound hung above its marquee, announcing our first program of Henry V, starring Lawrence Olivier, and co-featured with The Red Balloon, a fantasy by the French director Albert Lamorisse. Olivier and a chorus advise the audience to ”eke out our performance with your mind.” What better counsel for the rapture of art? What better counsel for a fledgling art-house on the scruffy Upper West Side? The New Yorker ran from 1960 to 1973.

The New Yorker began as a revival house. Our second program was Carl Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Marcel Pagnol’s Harvest, followed then by Fritz Lang, W. C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, Orson Welles, and films of the thirties and forties. Double bills of classics, screwball comedies, Westerns, gangster movies, and musicals were “mis-matched”—Vittorio De Sica’s Shoeshine got paired with Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train. Before we knew it, theaters around the country were copying our programs. Two years later, our distribution company was born with Before the Revolution, by a 21-year-old unknown Italian director, one Bernardo Bertolucci, and Pull my Daisy, a quirky Beat generation riff by Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie, narrated by Jack Kerouac. Now we would also play first-runs.

The New Yorker Theater was what Bertolucci called a kind of wild cinema university, like Henri Langlois’s cinematheque in Paris. It came at a ripe moment—when audiences came to view film as an art form and not just popular entertainment. Moviegoers flocked to the New Yorker not only from the neighborhood and nearby Columbia University but from the five boroughs. They could see Murnau, Eisenstein, Griffith, von Sternberg, Lubitsch, Rossellini and Renoir—what Jean-Paul Sartre called “the frenzy on the screen.”

What started as a “venture” became an adventure. In his Forward to the book, Martin Scorsese writes that The New Yorker and Other Scenes from a Life at the Movies is “a book about the love of cinema.” Love of cinema was evident on every page of our ledger, listing all of our programs, the source of the films, and attendance. In our youth, we had cut our teeth on Open City, The Bicycle Thief, Symphonie Pastorale, and I Know Where I’m Going. Now we had the privilege of playing what we loved: John Ford’s The Searchers, Busby Berkeley’s Gold Diggers of 1932, Satyajit Ray’s The World of Apu, Yasojiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story.

In that first decade of the New Yorker, no program was repeated.

The New Yorker Theater came at a ripe moment—when audiences came to view film as an art form and not just popular entertainment.

The sixties was a golden age in cinema, turbulent in politics, transitional in urban change. We were lucky, there at the hub where time and place converged: French New Wave, ‘68 uprisings at Columbia University, the emergence of the Upper West Side as a desirable neighborhood.

Dan had previously been the Eastern Story editor for Warner Brother, and had edited Film: An Anthology, an essay collection including Erwin Panofsky, James Agee, and Pauline Kael, which is used in classrooms to this day. He became the film critic for the Progressive Magazine, a liberal political monthly. I was teaching Spanish literature at Columbia University and witnessed first-hand those volatile events. The Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) declared our New Yorker a “liberated zone.”

Running a movie-house goes beyond flashing a film on the screen. Struggles and obstacles abound. Where to find the print? Will the projectionist arrive on time and be alert to reel change? How to cope with a powerful projectionist union? Do the bathrooms have enough toilet paper? How to apprehend pickpockets? How to meet labyrinthine city regulations? How to confront things that bug an exhibitor—whisperers, snorers, commentators, pigeons on the marquee? Such are the nitty-gritty details. Our theater was a family store: Dan the programmer, I the matron (legally required), my mother at the candy-stand, my father lobby vigilante. You had to pay attention to detail.

On Monday nights we started a film society with special programs. Silent films—D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance, Erich von Stroheim’s Greed, Fritz Lang’s The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse and Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari—were accompanied on the piano by Arthur Kleiner, a full-time pianist at the Museum of Modern Art. We had Special Series of one-week bills: Emil Jannings, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks, John Ford, Bette Davis, Mae West. Program notes were written by aficionados and movie mavens such as Bill Everson on The Golem, Jonas Mekas on Shor, Jules Feiffer on Gold Diggers of 1933, Jack Gelber on Foolish Wives, and Jack Kerouac on Nosferatu— program notes are included in the book.

The most successful film in our series was Triumph of the Will, which had not been shown in the United States for years. On the evening of June 27, 1960, a line formed around the theater, students from Columbia University eager to see that legendary film of the 1934 Nazi Part rally, shot in the Nuremberg stadium by Leni Riefenstahl.

From the outset patrons began filling our 300-page Guest Books in the lobby with their names and miscellaneous remarks—some of these pages appear in the book. There was an obvious hunger for film, thousands of film requests in several hundred ledgers. Susan Sontag asked for Vigo’s Zero de Conduite, Pagnol’s Les Lettres de Mon Moulin, Visconti’s Senso and La Terra Trema, and Tod Browning’s Freaks. P. Adams Sitney, avant-garde critic, wanted Luis Bunuel’s L’Age d’Or, The Great Dictator, and more Chaplin. W. H. Auden put in for Les Visiteurs du Sol, City Lights, any Carole Lombard film, any Jean Harlow, and early Marilyn Monroe. John Simon groused: “Improve the sound system and fix the seats.” And Dan replied, “Right on both accounts.” But on the very next page, a patron shot back: “Can anyone stop John Simon from mumbling during the show?” No one could.

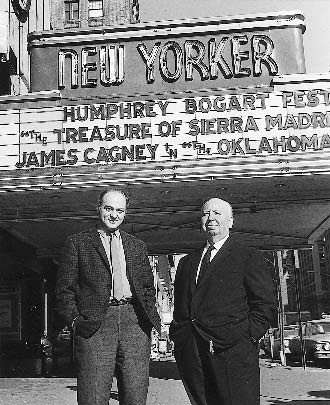

Dan Talbot & Alfred Hitchcock.

In the section On Location, I recount the opening of the New Yorker Book Store with Pete Martin and Austen Laber. Pete was the co-founder, with Lawrence Ferlinghetti, of the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, birthplace of the Beat Movement and of the literary magazine City Lights, of which five issues were published that included Manny Farber, Pauline Kael, David Riesman, Pete Martin and Parker Tyler. Our bookshelves were built by Manny Farber. The bookstore showcased young neighborhood writers, carried poetry, art books, little magazines and a line of newspapers. Isaac Bashevis Singer, who lived in the neighborhood, came daily to pick up the Forward.

The section “Cinephiles” describes our patrons. The theater became a hangout for film buffs from all walks of life: Columbia students Phillip Lopate and Morris Dickstein; critics Vincent Canby, Pauline Kael, Manny Farber, Richard Schickel, Eugene Archer, Andrew Sarris (proponent of the auteur theory), Jonas Mekas, Parker Tyler, Stanley Kauffmann, Peter Bogdanovich, Dwight Macdonald, and Susan Sontag; future film critic James Hoberman, Richard Avedon, Diane Arbus; the musical archivist Miles Kreuger; Jules Feiffer and Bruce Goldstein. Jules Feiffer did a mural that hung in our vestibule. But most were ordinary moviegoers.

I devote sections of the book to Sarris, Farber, Kael, Bogdanovich, and Canby, and to directors with whom we formed close relationships: Bernardo Bertolucci, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, and Ousmane Sembene. And I describe the genesis of Point of Order, made by Dan and Emile de Antonio, on the Army McCarthy hearings, and of Shoah, Claude Lanzmann’s eight-and-a-half hour work on the Holocaust.

We pursued works of human resonance that inform and perpetuate the art of cinema, touchstones to re-see over and over and learn from.

Peter Bogdanovich says the New Yorker Theater is where he got his education. Bruce Goldstein, repertory program director of New York’s Film Forum, who now devotes his career to getting better 35mm prints of classic films, was first made aware of that era with a screening of Gold Diggers.

As distributors, we launched seminal films and directors: Ousmane Sembene, now regarded as the father of African cinema; independent filmmakers Shirley Clarke, Jim Jarmusch, and John Cassavetes; Cinema Novo’s Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, and Carlos Diegues; Chris Marker; Jacques Rivette; Jean Eustache; Werner Herzog; Nagisa Oshima; and Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet.

We had the good fortune to participate as distributor and exhibitor in a score of memorable films: Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Decalogue, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul and Berlin Alexanderplatz, Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice, Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy, the Dardenne Brother’s La Promesse and Le Fils, Hirokazu Koreeda’s Afterlife, Werner Herzog’s The Land of Silence and Darkness, and the Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, Theo Angelopulis’s The Traveling Players, Ousmane Sembene’s Borom Sarret and Moolade, Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, and Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sancho the Bailiff.

At film festivals we were not on the lookout for blockbusters but for innovative works. We pursued works of human resonance that inform and perpetuate the art of cinema, touchstones to re-see over and over and learn from. The New Yorker Theater became a barometer to critical and popular taste, it helped to shape the sensibilities of a new generation.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!