Greg Robinson, a native New Yorker, is Associate Professor of History at l'Université du Québec À Montréal, a French-language institution in Montreal, Canada. A specialist in North American Ethnic Studies and U.S. Political History, he is also the author of the book By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Harvard University Press, 2001) and coeditor of the anthology Miné Okubo: Following Her Own Road (University of Washington Press, 2008). His historical column “The Great Unknown and the Unknown Great,” was a well-known feature of the Nichi Bei Times newspaper.

My book offers a new look at a familiar subject, Executive Order 9066 and the removal and confinement of West Coast Japanese Americans during World War II (commonly called the Japanese internment).I realize that it may come as a surprise to readers that there is anything new to say after all the memoirs, histories, plays, documentaries, and so forth that have appeared on this subject. Part of it is that my book takes account of a whole mass of new scholarship, including my own research, and of different newly available sources.

This new information deepens our knowledge of the wartime events, though it does not really change our view. What is very new and transformative about the book, on the other hand, is that it daringly breaks through the narrow framework of time and space in which the subject has always been discussed.

First, I go beyond the wartime period and discuss the postwar and prewar years. And not just as backstory—this is a main part of the narrative. In particular, the book reveals for the first time the massive government surveillance of Japanese communities during the 1930s, and the construction by the Army and the Justice Department of what were termed concentration camps for enemy aliens. All of this helps show how much of a momentum for mass suspicion and arbitrary treatment of Japanese Americans on a racial basis had been created even before the war.More importantly, A Tragedy of Democracy is the first-ever North American history of confinement.

The book breaks new ground by looking at the history of the camps in the United States alongside the Canadian government’s wartime removal of 22,000 citizens and residents of Japanese ancestry from the Pacific Coast of British Columbia. I also compare official policy toward Japanese Americans with that in wartime Hawaii, where fears of “local Japanese” led to a declaration of martial law after Pearl Harbor, the establishment of a military dictatorship, and replacement of civilian courts by military tribunals. I also shed new light on the histories of the Japanese Latin Americans kidnapped from their home countries and interned in the United States, plus the 5,000 Japanese expelled from Mexico’s Pacific Coast.By studying Japanese American confinement within a continental—indeed international—pattern, we can learn more about its causes as well as the results for its victims.

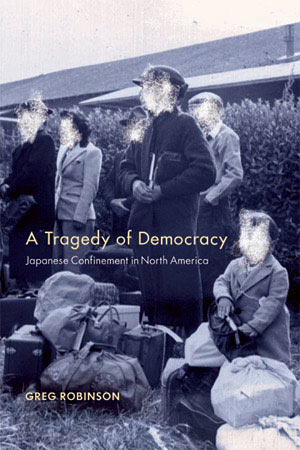

Greg Robinson A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America Columbia University Press 408 pages, 9 x 6 inches ISBN 978 0231129220

We don't have paywalls. We don't sell your data. Please help to keep this running!