Jennifer Lind

Sorry States: Apologies in International Politics

Cornell University Press

256 pages, 6 1/8 x 9 1/4 inches

ISBN 978 0801446252

In order for countries to reconcile after terrible wars, must they apologize, pay reparations, and otherwise “come to terms with the past”?

A powerful conventional wisdom, based on the postwar experiences of West Germany and Japan, says yes. West Germany made extensive efforts to atone for wartime crimes—formal apologies, monuments to victims of the Nazis, and candid history textbooks; Bonn successfully reconciled with its wartime enemies. By contrast, Japan routinely ignites the ire of its former adversaries when its leaders deny atrocities or visit memorials that honor the architects of Japanese imperialism. Each release of new history textbooks in Japan sparks regional furor as books often gloss over past aggression and atrocities. Tokyo has paid little in the way of reparations to victims; its apologies have been derided as too little, too late. Observers say that the suspicion of Japan that lingers in Asia is caused in great part by Japan’s failure to face its past.

But is it this simple? What is the relationship between apologies, memory, and international reconciliation?

To answer these questions, my book Sorry States: Apologies in International Politics examines the post-World War II cases of South Korean relations with Japan, and French relations with Germany. I find that, as many people have argued, denials of past aggression and atrocities do fuel distrust and elevate fears among former adversaries. More than sixty years after the war, Japan’s failure to admit its atrocities continues to poison relations with not only South Korea but also China and Australia.

Across the globe, West Germany’s willingness to accept responsibility for the crimes of the Nazi era, and the absence of denials or glorifications of that past among mainstream West Germans, reassured Germany’s World War II adversaries. To this day the French and British monitor German remembrance for signs of revisionism and are reassured by their absence. Both the German and Japanese cases thus suggest that avoiding denials and glorification of past violence facilitates reconciliation.

Though I find strong support for the widely accepted view about the damaging effects of denials, my book challenges the prevailing wisdom in two important ways. One, I show that many countries have been able to reconcile with very little contrition or self-reflection about the past. Two, I argue that contrition is highly controversial and likely to cause a domestic backlash that alarms—rather than assuages—outside observers.

Because of backlash, I find that apologies and other such polarizing gestures are unlikely to soothe relations after conflict. Less accusatory remembrance, conducted bilaterally or in multilateral settings, holds the most promise for international reconciliation.

Many countries have been able to reconcile with very little contrition or self-reflection about the past … contrition is highly controversial and likely to cause a domestic backlash that alarms—rather than assuages—outside observers.

Understanding what promotes international reconciliation is a key but neglected question in world politics. Scholars who study the phenomenon of war have explored many of its aspects—when do wars start, how do they end, who wins, and so on. Indeed, these are critically important questions. However, analysts have paid less attention to another key issue—the causes of peace. Not that this has been entirely unexamined. But the role of ideas in peacemaking, and specifically memory, has so far received little attention.

Scholars, journalists, and other analysts have explored how countries deal with their own violent history, and how memory and justice affect national development, democratic consolidation, and stability. Examples include the cases of South Africa and the role of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; various Latin American countries and how the victims of dictators and military juntas are remembered or forgotten; also Rwanda and how its society has rebounded from its terrible recent past. In my book I wanted to connect the concepts from this literature about the domestic realm to the realm of international politics. I ask how the ways that countries remember and atone for the past affect the promise of international reconciliation.

I grew interested in this topic because, as an East Asia specialist, I could see the powerful role of memory in regional relations. Every day seemed to bring another news story about a textbook crisis between Japan and its neighbors, a rift in Sino-Japanese relations about history issues, or an uproar over a gaffe made by a Japanese politician. These issues seemed to weigh heavily over the region’s politics, yet I found that my international relations toolkit offered little to help me understand them. That’s why I wrote this book.

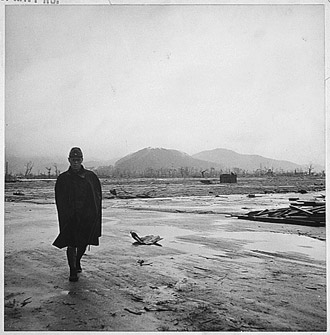

A Japanese soldier walks through the ruins of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing. Photo courtesy of National Archives.

Writing Sorry States surprised me in many ways. My first surprise came when I noticed a striking pattern in Japanese apologies and other gestures of “contrition.” One leader’s attempt to apologize prompted denials, justifications, and other denunciations from other leaders and elites. I had known that Tokyo frequently apologized, and that Japanese leaders often made statements denying past atrocities, but I had never seen, and no one else had ever commented on, a connection between the two.

I called this phenomenon “backlash,” and once I became attuned to it, I began seeing it all over the world. In Britain, the United States, France, Austria and many other countries, proposals to apologize for past wrongs prompted significant domestic outcry. This was not a phenomenon unique to Japan. Indeed, it’s a predictable response when someone proposes that instead of remembering our dead loved ones as heroes and patriots, we instead apologize for their actions and label them war criminals.

My finding about backlash was totally unanticipated and became a central argument in the book. For if apologies cause backlash—and other countries observe and are alarmed by this backlash—then contrition would not, in fact, be a useful tool in reconciliation.

In the book I discuss when backlash is more or less likely to occur—noting its relative absence in Germany—and discuss how this issue is one that scholars need to explore further before we can truly understand when contrition might help or hurt. But at this point, the likelihood of backlash casts serious doubt on that strong conventional wisdom about the healing power of international apologies.

In the case of Franco-German reconciliation, I found another surprise. Everyone, myself included, believed in the power of atonement in reconciliation because the Germans had been very contrite, and they had so successfully reconciled with the French and others. It is true that Germans engaged in profound—indeed, historically unprecedented—atonement. But they didn’t start this right away—it was only after the Left took power in West Germany, in the mid-1960s.

It is also true that France and Germany reconciled, but—as evident in poll data, summitry, and other diplomacy—they did so immediately after the war, in the late 1950s. In other words, the medicine that supposedly had cured the disease wasn’t applied until after the patient was healed. Reconciliation came first—then atonement.

The surprise here was that the country wasn’t particularly apologetic (German memory was not very contrite at the time of Franco-German reconciliation), yet reconciliation occurred anyway.

Therefore I find that Japan’s denials of its past atrocities were harmful, and that the absence of such denials or justifications of the war and Holocaust in West Germany indeed helped promote the German reconciliation. But my book contradicts those who say that reconciliation in Asia is doomed until Tokyo offers “German-style” contrition.

It is true that Germans engaged in profound—indeed, historically unprecedented—atonement. But they didn’t start this right away—it was only after the Left took power in West Germany, in the mid-1960s. The medicine that supposedly had cured the disease wasn’t applied until <em id="">after</em> the patient was healed. Reconciliation came first—then atonement.

The other day I saw a bumper sticker that said “No peace without justice!” It sure sounds good, and before I writing the book I would have reacted to it with an “amen, sister.”

But Sorry States finds otherwise. Clearly there can be peace without justice: we know this from Franco-German reconciliation, as well as other notable cases such as U.S. relations with Japan and West Germany after the war. The United States has never expressed contrition about its incendiary bombing campaigns against Germany or Japan, despite the fact that those attacks killed more than a million civilians. But the lack of U.S. contrition has not prevented reconciliation between Americans and Germans or Japanese.

Furthermore, because the pursuit of justice (proposals to pay reparations, build monuments, and issue apologies) is so politically charged, it may actually end up undermining peacemaking. Debates about the past frequently feature denials and justifications of past violence. Other countries observe these sentiments, and become alarmed about what they suggest about the country’s future foreign policy intentions.

What are countries to do? If denials harm bilateral relations, and apologies may do so indirectly by prompting backlash, how should countries remember the past in order to promote reconciliation?

One strategy, used successfully by West Germany and France, is to construct a shared and non-accusatory narrative. Rather than frame the past as one actor’s brutalization of another, leaders can structure commemoration to cast events—as much as possible—as shared catastrophes. Countries can remember past suffering as specific examples of tragic phenomena—war, militarism, or aggression—that afflict all. For example, rather than lament German brutality, the settings and tone of Franco-German commemoration (Reims cathedral in 1962; Verdun cemetery in1984) highlighted the suffering that militarism and European anarchy had brought to both peoples, which underscored the need for European unity.

Another strategy is multilateral. Multilateral textbook commissions—used extensively in Europe and also recently in East Asia—offer another promising approach. Because multilateral settings do not wag a finger at one country in particular, and because multilateral institutions confer legitimacy, conservatives are less likely to mobilize against them.

These approaches do have significant drawbacks. If justice is the policy goal, they are clearly wrong. They downplay the heinous acts that occurred and divert attention from the people and governments who committed them. But, as John Kenneth Galbraith famously commented, “Politics is the art of choosing between the disastrous and the unpalatable.” These strategies are unpalatable in many ways—yet they are the best course for international reconciliation.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!