Rob King

The Fun Factory: The Keystone Film Company and the Emergence of Mass Culture

University of California Press

276 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0520255388

ISBN 978 0520255371

The Keystone Film Company is one of those film studios whose name immediately conjures up a host of associations. Founded in 1912 by Irish-Canadian Mack Sennett, Keystone was the studio where many of the legends of silent film comedy first became stars – Mabel Normand, Ford Sterling, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Charlie Chaplin, and Ben Turpin, among many others. It was a company that defined a hugely influential style of fast-paced knockabout: the frantic Keystone cops, crazy chases with flivvers and police wagons, and, of course, the Bathing Beauties – all of these made an indelible mark on US culture at the beginning of the twentieth century. Keystone is unquestionably the most important film company in the history of American comedy.

For me, though, the crucial issue is to ask why Keystone was so influential. Why this style of screen comedy, rather than any other? After all, it’s not as though the studio was the only one, or even the first, to put slapstick comedy on screen. There were other comic filmmakers prior to Keystone’s, many of whom were extremely popular (people like Augustus Carney and John Bunny, to say nothing of the French comedian Max Linder). If we really want to understand the nature of Keystone’s contribution, it seems to me, we have to adopt a perspective that looks beyond the studio gates to consider the company’s meaning in the larger cultural landscape of the time.

In its broadest strokes, this is what The Fun Factory tries to do. The book is at once a studio history and an analysis of that studio’s cultural moment.

Why people laugh, who and what they laugh at – these are historical categories that change over time.

The French philosopher Henri Bergson famously described laughter as a “social gesture.” It’s a quote that has been a watchword in my own thinking about comedy. Why people laugh, who and what they laugh at – these are historical categories that change over time. The history of comedy is in this sense nothing but the history of the changing social patterns that produce and permit laughter.

Comedy tends to cluster around points of tension within a given social order, where established patterns and relations are beginning to give way to new patterns, new relations. Comedy translates those conflicts into jokes and provides an articulation of social contradiction at moments of historic change. These are some of my basic methodological assumptions.

Now, if we can accept these points, it makes sense to foreground issues of culture and society in any understanding of film comedy. The question then becomes: how can we think of Keystone’s history in these terms?

One needs to begin here with the recognition that the decades surrounding the turn of the century represent a crucial watershed in the remaking of working-class culture. At every level, plebeian cultural forms were being gradually integrated into the branches of a newly centralized culture industry: in live entertainment, as vaudeville impresarios like B. F. Keith repackaged the boozy, licentious concert saloon as respectable variety theater; in sports, as baseball shed the disreputability of the “Beer and Whiskey League” and began its transformation into the “nation’s pastime”; and, of course, in film, as immigrant nickelodeon operators like Carl Laemmle and William Fox rose to become presidents of major film companies catering to nationwide “movie-mad” audiences. In each case, important centers of plebeian recreation and sociability were either displaced or transfigured by new sites of mass or cross-class entertainment.

The development of slapstick comedy, which I trace through the history of the Keystone Film Company, follows a precisely similar profile, what can be described as a shift in slapstick’s status as a term of class culture to its centrality in an emergent mass culture.

Keystone brought together a group of filmmakers from immigrant, working-class backgrounds, most of whom came to the studio with experience in popular theater and burlesque. During the studio’s early years, they fashioned a style of film comedy formed from the roughhouse traditions of working-class comic theater. The world of Keystone’s early films was thus far removed from the more genteel developments in dramatic filmmaking associated with pioneers like Cecil B. DeMille or D. W. Griffith (it’s not well remembered, for instance, that the crazy chases for which Keystone is still so famous originated as explicit parodies of Griffithian race-to-the-rescue melodrama). A history of Keystone’s early years can thus illuminate much about the place and role of working-class popular culture at the advent of the twentieth century.

At the same time, Keystone’s career also reveals how slapstick’s plebeian tones were softened and transformed by cinema’s participation in the emergent mass culture. Beginning in 1915, significant changes began to occur in the studio’s comic style, when Keystone was swept up in the formation of new corporate organizations designed to market film to a broader, cross-class audience. Faced with the commercial imperative of having to reach out to a larger public – one that would include both men and women, blue-collar and white-collar viewers, the working and genteel classes – Keystone’s filmmakers innovated with new “mass” forms of comic representation. What one sees in films of this later period is first, a growing reliance on genteel narratives and upper-class settings; second, an increased emphasis on the comic spectacle of out-of-control tin lizzies, airplanes, flivvers, and assorted “uproarious inventions”; and third, the titillating display of the famous “Bathing Beauties” who virtually defined the studio’s later history.

The thesis of The Fun Factory, in this sense, is simply this: that the history of Keystone traces the contours of, and sheds light upon, the development of early mass culture. Such an approach, I believe, not only sheds light on Keystone’s broader historical significance, it also helps elucidate the book’s central assumption – namely, that understanding laughter is a way of understanding cultural change.

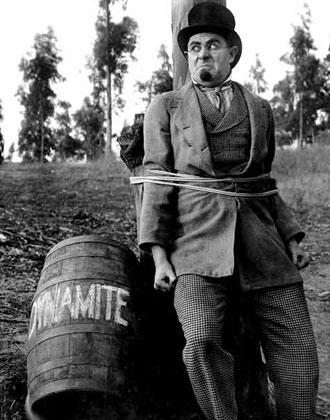

Ford Sterling in Love and Dynamite (1914)

It can admittedly be difficult to sense this kind of “sociology” of comedy – in large part because of our nostalgic fixation on images of custard pies and Keystone cops. So a brief example might be helpful.

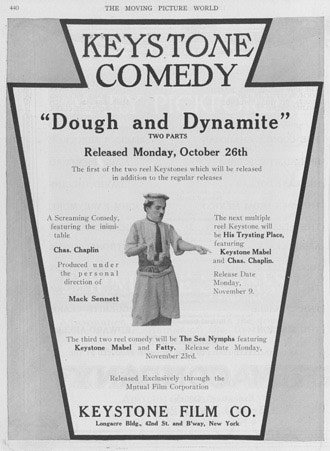

The film Dough and Dynamite provides an interesting test case. First released in November 1914, Dough and Dynamite is one of the few “famous” Keystone comedies – that is, it’s one of the few films that might have been seen by non-specialists. Notably, it was this film that set its star and director, a certain Charles Chaplin, on the course of bone fide film stardom. Even at the time, film critics and writers pointed to this movie as the one that set “everyone talking about the new funny man.”

At face value, the movie is full bore, rough-and-tumble slapstick: Chaplin and his co-star, Chester Conklin, play waiters in a teashop who are put to work in the adjoining bakery when the bakers go on strike. What unfolds is a series of chaotic scenes that, in the words of one noted Chaplin biographer, have seemed little more than “an excuse for ... the fun to be had from sticky dough.” Certainly, there’s a lot of fun to be had: bags of flour, exploding loaves of bread, doughnuts – all contribute to the film’s dough-drenched knockabout.

But is this all that the film is about? Is it adequate to describe the film as simply a comedy about “sticky dough”?

As soon as we pay attention to the broader context of working-class life, it becomes clear that the film was in fact profoundly engaged with recent events in the Los Angeles labor movement. The contemporary point of reference for Dough and Dynamite was the hard-fought struggle of the city’s bakers’ unions for better working conditions, widely reported in the Los Angeles labor press. In what had been the most conspicuous labor crusade in southern California in the early teens, the Jewish and general bakers’ unions had joined forces in an ambitious campaign of striking at open shop bakeries.

The bakery setting of Dough and Dynamite was, then, far more than the opportunity for fun with “sticky dough” that a more insulated appropriation of this film would suggest. Rather, it was a point of engagement with current labor issues. But as soon as we realize this, then we have to ask a number of further questions about representations of labor within early cinematic mass culture. Why was it a film about a local bakers’ strike, of all possible subjects, that made Chaplin a star? How did audiences at the time respond to these images of striking workers and by what processes did those images function as comedy?

Now, admittedly, Dough and Dynamite is an exceptional case, and it’s certainly not my argument that Keystone’s early films are always about strikes, unions, and other class issues. Still what Dough and Dynamite does show – and in an unusually literal way – are the ways these movies were involved in the broader plebeian culture of their time. What one finds in these films may not be “representations of workers” in the realist sense characteristic of, say, social problem films. Even so, the films do present an array of comic characters and comic formulas that derived quite directly from the traditions and experiences of working-class life in turn-of-the-century America.

The Fun Factory devotes chapters to many of these – to the glamorous Bathing Beauties and new models of femininity, to ethnic stereotyping and the increased immigration of the period, and to the pace and style of Keystone comedy and the broader context of industrialization, among other areas.

The classic comedies of the 1920s are the culmination of a process; the history of earlier companies such as Keystone show that process in development.

If there’s one thing that I’d hope for this book, it is that it stirs up interest in the early phase of film comedy’s development – that is, in comedies produced prior to the more well-known features of the 1920s.

Of course, silent comedy remains popular to this day; yet its image has long been dominated by the comedians of the late silent era – people like Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Laurel and Hardy. Show an audience an acknowledged classic like Keaton’s The General (1927) and you’re going to get a lot of laughs; show a short comedy from the 1910s and, like as not, it won’t play quite as well.

Early comedy can often seem a quite alien terrain, especially to those encountering it for the first time. And yet, rather than dismiss these films for lacking the polish of their later counterparts – a very unhistorical thing to do – we need to let them pique our curiosity, and let our curiosity guide us toward new discoveries. We need to see that the classic comedies of the 1920s are the culmination of a process; the history of earlier companies such as Keystone show that process in development.

There’s much to be learned, I believe, from studying that process. The parameters of what made people laugh a century ago are obviously quite different from today; but in that very difference lies the possibility for considerable historical exploration and insight.

Fortunately, there now exists an increasing number of venues where these films can be viewed and discussed, studied and debated – annual conventions like Slapsticon in Washington, DC, and the Slapstick festival in the UK, websites like silentcomedians.com and silentcomedymafia.com, as well as media companies putting hard-to-find comedies on commercial DVDs, like Laughsmith and AllDay.

The historical work to be done here remains enormous, of course, but there’s a lot of fun to be had in doing it.

.jpg)

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!