Alfonso Quiroz

Corrupt Circles: A History of Unbound Graft in Peru

Johns Hopkins University Press

552 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0801890765

ISBN 978 0801891281

Corruption has existed since the earliest civilizations but documenting and writing its history has not been easy. In the case of Peru, tackling through detailed research the challenges to writing a history of corruption, one finds abundant evidence of structural corruption. This prevalent type of corruption is defined broadly as the persistent abuse of power for private gain. In successive phases, over a stretch of more than 250 years, systemic corruption seriously undermined Peru’s basic institutions and promising possibilities for development. To untangle this intricate knot Corrupt Circles follows the guiding threads left for posterity by courageous reformists and opponents of unchecked graft in a poor society. The book is intended to be read as a story of the perils of greed and abuse past and present.

In Peru, the interested mismanagement of the state and national resources inflicted endemic social harm over time. Evolving corrupt schemes and the networks of persons who implement them affected strategic sectors. Initially it was colonial mining and contraband trade that exhibited deep problems ascribed to rampant corruption. After independence similar hurdles afflicted republican guano income and public debt administrations often bribed by foreign contractors of public works and arms procurement. In the twentieth century corruption thrived under military dictatorial oppression, preyed on deals of oil exploitation, and most recently, drug interdiction. Corruption reached a zenith under the cover of gross undemocratic abuses during the infamous Fujimori-Montesinos regime.

The exposure of this hidden history leads to a reinterpretation of Peru’s evolution and a reevaluation of the importance of transparency and individual and collective efforts at critical reform. In our own times of global frauds and political corruption these insights apply beyond a single, albeit paradigmatic, Latin American country.

Each new cycle of corruption brings new means and schemes imbedded in technological and organizational changes.

Corrupt Circles combines different tools of economic, political, and historical analysis to identify the costs and consequences of corruption in a developing society. The book particularly adopts and applies recent methodological breakthroughs by economists who conceive corruption as an obstacle for overall development. Only marginally does this analysis treat corruption solely through the angle of public perceptions, a fleeting standard for measuring it. The book’s main object is the hard evidence of corruption’s costs transpired in governmental and institutional malfunction, failure, and wasted opportunities.

Institutions as well as policies suffer costly biases if they are directed by corrupt officers or policy makers swayed through bribes rather than goals of efficiency. Certainly there continues to be a lively academic debate over these issues. Armed with a considerable arsenal of quantitative data, I venture to estimate the direct and indirect costs of graft in different cycles and government administrations in Peru.

On average corruption costs accounted for as high as 30 or 40 percent of Peru’s total public budget expenditures and 3 to 4 percent of gross domestic product. I confine most of these calculations to the sole appendix of the book, to avoid interrupting the main narrative built upon unraveling corruption scandals and the controversies they entailed.

The political underpinnings of corruption are evident through the almost perennial absence of checks to the executive branch of government. Despite constitutional blueprints, often violated, political practice in Peru has subjected the legislative and judicial branches to the influence or control of presidential power. Abuse of political power in a context of viceregal or caudillo patronage went hand in hand with the draining of scarce public resources for private or party benefit. Modern political parties involved in electoral democracy also profited from crooked means to obtain and maintain power. Political leaders and officers engaged in covert pacts and interested understandings with other political forces so as to buttress customary impunity.

Corruption can also encompass both continuity and variation in history. This is a key notion to understand the phenomenon of corruption. Each new cycle of corruption brings new means and schemes imbedded in technological and organizational changes. An illustration can be the public contracting of railway construction in the 1850s and 1860s. As this history of graft illustrates, corrupt and corrupting agents always found new and sophisticated ways to illegally funnel public resources into private hands. To visualize the changing nature of a paradoxically persistent encumbrance, the book adopts a long-term perspective.

The main historical sources I analyze are colonial treatises, official accounts and inquiries, diplomatic reports (from British, French, Peruvian, Spanish, and United States archives), legislative investigations, judicial trials, declassified documents, business records, memoirs, self-incriminating audio and video transcripts, journalistic accounts and investigations, among several other.

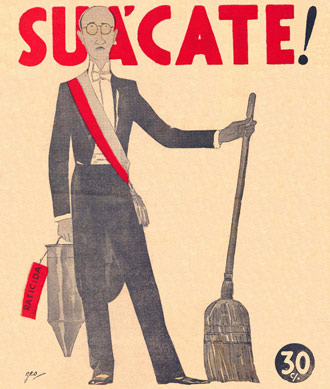

A Peruvian president's failed intention to exterminate corruption, 1945. Courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional del Peru.

Description of the personal efforts of distinguished past foes of corruption is a leitmotiv set up in pages 21-25 and repeated in the opening sections of each subsequent chapter.

The first pages of chapter 1 frame the dilemma of don Antonio de Ulloa (1716-1795), an enlightened governor of the mining center of Huancavelica, a strategic source of mercury in the viceroyalty of Peru in 1757.

Armed with a reformist training and honest intentions, Ulloa detected day after day what he termed his “purgatory” in dealing with appalling maladministration and dangerous neglect of the mines. Counting with the support of the royal council in Madrid, Ulloa was very aware of the urgency of reforming the management of mercury supply essential for the amalgamation process in silver production. Silver was the main source of American wealth fueling the Spanish empire and its involvement in European wars. However, in Huancavelica Ulloa found that groups of miners, merchants, and even priests conspired to drain as much private benefit out of the royal mines and the indigenous population. These corrupt networks had a long reach all the way to the viceregal court in Lima.

Ulloa’s reformist measures were bitterly opposed in Huancavelica. He even got in deep legal trouble in Lima accused of the same crimes he was trying to stamp out. One viceroy, the highest authority in Peru at the time, became Ulloa’s most bitter enemy. After several years of troubles and persecution, Ulloa was able to leave Peru in defeat despite his valiant fight.

The letters, reports, and analytical essays Ulloa wrote, to inform Madrid how corruption operated in Peru, are true historical windows for studying connections between past and more recent manifestations of costly graft. Ulloa’s Noticias secretas de América, coauthored in part with his fellow naval officer Jorge Juan and published only in 1826, can be considered one of the first anticorruption treatises in Spanish America.

Other valiant personal and mostly frustrated efforts at reform included the actions and writings of Domingo Elias (1805-1867), Francisco García Calderón Landa (1834-1905), Manuel González Prada (1844-1918), Jorge Basadre (1903-1980), Héctor Vargas Haya (b. 1928), and Mario Vargas Llosa (b. 1936). Their stories can be followed in the context of the corrupt administrations they had to deal with. Through their detective, journalistic, and activist work, and together with a host of new anticorruption reformists arising just after the fall of Fujimori, these admirable individuals have contributed to hopes that one day the damaging excesses of corruption will be controlled in Peru.

The stiff punishment applied by Peruvian courts to those who led the most recent frenzy of corruption in the 1990s is an auspicious start that could be, however, easily reverted.

To document and write the history of corruption in Latin America and other developing parts of the world, there is still a lot of work ahead.

I hope for my book to contribute to the historical treatment of the persistent phenomenon of uncurbed corruption, a burden too heavy to carry by impoverished citizens. The historical visualization of the problem and its negative consequences can help present endeavors to fight and control corruption. A thorough anticorruption reform must include constitutional checks against it and an end to the customary tradition of impunity. The stiff punishment applied by Peruvian courts to those who led the most recent frenzy of corruption in the 1990s is an auspicious start that could be, however, easily reverted.

Anyone who travels or engages in business in those parts of the world were corruption reaches high levels should be aware of the long history, enormous costs, and past efforts at curbing graft. Most importantly, by learning from past anticorruption efforts, the citizens of countries flagellated by corruption will hopefully rise to the task of punishing and not condoning the corruption of “strong” governments that deceitfully appeal to popular support.

The danger of uncontrolled corruption also exists in developed countries were corruption has been historically curbed. Corruption and its concomitant abuse of power could raise its ugly head at any moment if the walls that circumscribe it are not periodically reinforced.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!