Peter Conn

The American 1930s: A Literary History

Cambridge University Press

280 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN: 978 0521734318

With the exception only of the Civil War, Americans faced in the Depression of the 1930s the most wrenching and divisive domestic crisis in their history. An economic structure that had seemed unshakable simply collapsed, and neither experts nor ordinary citizens were ever sure why.

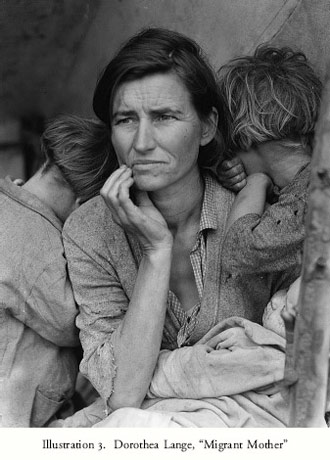

The political and economic debates of the decade have produced a long shelf of books, and the current financial slump has renewed interest in those controversies. However, the literature and art of the thirties have been less thoroughly documented. A few images – photos of soup kitchens and Dust Bowl migrants – have survived, which offer an important but selective and ultimately misleading version of the Depression years.

In fact, the 1930s were years of rich and diverse creativity, in which artists and writers responded to the crisis in a wide assortment of ways. In the imagination of the thirties, optimism competed with pessimism, and comedy co-existed with tragedy.

My book discusses well over a hundred novels, stories, plays, and paintings, offering one of the most comprehensive accounts of this decade ever published. In addition to fiction, the book refers to much of the nonfiction writing of the period, including biographies, memoirs, and works of history, and quite a few of the Pulitzer Prize winners.

Among the men and women whose work is explored in The American 1930s are William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, Dorothea Lange, John Dos Passos, Pearl S. Buck, Carl Sandburg, Zora Neale Hurston, Thomas Hart Benton, Langston Hughes, Grant Wood. I also include a host of less familiar writers and artists.

The 1930s were years of rich and diverse creativity, in which artists and writers responded to the crisis in a wide assortment of ways. In the imagination of the thirties, optimism competed with pessimism, and comedy co-existed with tragedy.

In all of my books, my chief purpose is to examine the ways in which history and imaginative works can illuminate each other. How do the events of a particular time and place shape the novels, stories and visual art of that historical moment? And how in turn can those fictional works help us understand our national past?

The Depression years provide an especially promising period for examining such questions. Because of its scale and persistence, the economic trauma affected large numbers of Americans directly; and virtually everyone followed the course of events through coverage in the nation's newspapers, magazines, radio broadcasts, and movie newsreels.

The key point I demonstrate is that Americans responded in a wide variety of ways to this shared crisis. A recent review in the New Yorker characterized the book aptly as offering “a corrective to the assumption that the Depression decade was dominated culturally by leftist aesthetics and politics” and as revealing “fascinating vicissitudes of art and history" (The New Yorker, March 30, 2009).

In short, The American 1930s offers a revisionist history of the art and literature of the 1930s. The case studies I present accurately reflect the yeasty and complex responses that Americans displayed to the turmoil of the period. Some Americans recoiled in disappointment and anger, and called for revolution. At the same time, others embraced all the more fervently the essential rightness and continued relevance of traditional national propositions.

Every revolutionary manifesto can be matched by a call to re-affirmation. In 1932, Malcolm Cowley, Langston Hughes, Edmund Wilson, and the other intellectuals who published Culture and the Crisis demanded a revolution and supported William Z. Foster, the Communist candidate for president. A couple of years later, on the other hand, regionalist painter Grant Wood, in his Revolt Against the City (1935), argued, “during boom times conservatism is a thing to be ridiculed, but under unsettling conditions it becomes a virtue.” Wood detected, in the opinion of writer Steven Biel, a “powerful yearning for security” as the dominant mood of the time.

Those diverse understandings led to diverse imaginative expressions – in effect a debate over the meaning of America. The task I have taken up is to provide a through line for exploring that rich heterogeneity, by tracing one of the main subjects to which the decade’s writers turned again and again: the past. The writing of the 1930s comprises an extensive and complex engagement with the past, in myriad forms: the memoirs and biographies of influential individuals, and the factual and imaginary histories of the United States and other nations.

Let me give a few examples. Several of the popular biographies of the 1930s – including some of those that won Pulitzer Prizes and other awards – recreated the lives of earlier Americans as a way of making a statement about the turbulence of the Depression years.

Marquis James’s two-volume biography of Andrew Jackson, for instance, presented the seventh president as a protector of ordinary men and women against the power of early nineteenth-century bankers. James explicitly invokes the parallel with Franklin D. Roosevelt and his struggles with what he called “the economic royalists” of the 1930s. Carl Sandburg’s monumental, six-volume life of Abraham Lincoln also rhymed with the thirties: Lincoln was the plain man, the man who had grown up in poverty, and whose example should inspire a later generation to rely on the genius of democracy to find solutions in hard times.

Many of the decade’s novelists also used historical subjects to comment on present discontents. Kenneth Roberts wrote several bestsellers set in and around the Revolutionary War. Adopting a pro-British point of view – Benedict Arnold is the hero of several of the novels – Roberts indirectly took his stand on the politics of the 1930s: a fervent enemy of New Deal, Roberts did his best to undermine the legitimacy of what he saw as Roosevelt’s revolutionary agenda.

In an effort to make the debate in the thirties over American identity racially inclusive, African-American painters Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence created images of black history.

Illustration 3. Dorothea Lange, "Migrant Mother"

Many browsing readers – this is certainly true for me – would take a look at a book’s introduction. Here, the introduction gives a relatively full explanation of what I am up to in my book.

On the other hand, a reader might take a first look at the epilogue. Here, the Epilogue does more than review and survey what the earlier chapters have accomplished. I recall the New York World’s Fair of 1939-1940. The Fair’s inspirational symbolism was calculated and timely. Fully ten years after the Crash, the nation’s crippled economy continued to resist the solutions of the New Deal. The Fair, mainly intended to generate revenue for the city, turned into one of the great public events of the decade. For a few hours at least, visitors could leave behind the dreariness of unemployment and class struggle and enter an ideal world of rational planning in which social problems found elegant solutions. As conceived by the corporate leaders of General Motors, General Electric, and Kodak, among others, America's future would be orderly, clean, lily-white, and free of smog and slums.

It was called “The World of Tomorrow,” but in fact the World’s Fair brought the past and future together, often in unexpected ways. While the Fair was famous for its predictions of the technological marvels that lay in store in the decades to come, it was officially conceived as a celebration of the hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of Washington’s inauguration in New York. The Fair counseled hope, but the hope was rooted in nostalgia: like its sleek, modern buildings, America would rise out of stagnation and discover a prosperous carefree future – a future that bore some striking resemblances to the past.

For example, visitors to the Perisphere – one of the Fair’s two iconic buildings, along with the Trylon – stood on two rotating platforms that circled “Democracity 2039.” The city of the future would be small in scale, set in wooded preserves, with machinery subordinated to human use. Upon inspection, the city as foreseen by the designers of Democracity was less urban than suburban, despite disclaimers to the contrary. It was a dream of the past decked out in the deceptive glamour of the future.

In short, the World’s Fair offers a compressed illustration of the argument I make throughout the book. The turbulence of the Depression decade impelled Americans toward a sustained and lively inquiry into the past, as a way of finding answers to the questions posed by the longest economic crisis in the nation’s history.

No single explanation or formula will be sufficient to encompass the multifarious motives and choices through which the men and women of vanished decades defined themselves.

Taken most generally, my book argues against the simplification of history. Any attempt to recover the past must acknowledge that no single explanation or formula will be sufficient to encompass the multifarious motives and choices through which the men and women of vanished decades defined themselves.

In that sense, the particular example of the American 1930s merely exemplifies a larger point. To see the thirties exclusively as “the red decade” is to reduce a complex palette to a monotone. I quote in the book the journalist Robert Bendiner, whose family lived a hand-to-mouth existence through the American thirties: “It has always seemed to me fatuous to fix a single label on a whole decade – as though the Nineties were gay for immigrant ladies in the garment sweatshops of Manhattan or the Twenties stood for hot jazz in the mind of Calvin Coolidge.”

In other words, instead of ignoring or manipulating the past to fit the presuppositions of two or three hackneyed adjectives, it is important to address the facts and texts of any historical period and follow their lead. This is what I have tried to do in The American 1930s. Again, the New Yorker review captures the book well: “despite the strain of the Depression, the United States in the thirties was ‘a place of enormous ideological and imaginative complexity’.”

(This interview incorporates excerpts from The American 1930s: A Literary History, reproduced here with permission of Cambridge University Press.)

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!