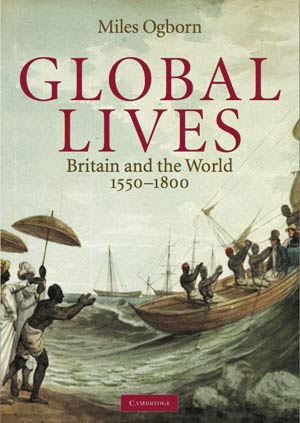

Global Lives aims to offer an introduction to global history between 1550 and 1800. Focusing on Britain’s changing relationships with the rest of the world, it sets out the contours of the forms of globalisation, or global connection, that developed across this two hundred and fifty year period. However, this is not simply a survey of the “Big Picture” history of the rise of the British empire. In order to engage readers with processes such as European settlement in North America, the slave trade, and navigation in the Pacific, Global Lives tells this history through over forty brief biographies of a range of individuals from Queen Elizabeth I to Mai, the first Polynesian to visit Britain.This unique combination of global history and biography – the big picture and the fine-grained detail – aims to breathe some real life into what are too often thought about as abstract and anonymous historical and geographical processes – the development of trade routes, the spreading of settlement and the forging of empires.In Global Lives, those who lived out these globalising processes are put centre stage. The history of early modern globalisation is told through the biographies of rulers and revolutionaries, the enslaved and the free, and profiteers and pirates. Each person is understood as trying to operate in the circumstances within which they found themselves. Each person is seen as trying to make a difference, for good or ill, for themselves and others. Each person, whether they travelled long distances or stayed close at home, is seen as playing a part in making this new global history and geography.