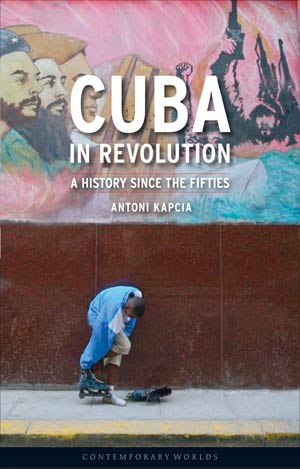

Essentially this book was written in an attempt to explain to the interested lay reader why a curious phenomenon still called 'the Cuban Revolution' had managed to survive for so long, despite everything that had happened to it or been thrown against it over five decades. Whatever one feels about the Revolution, its greatest achievement may well be the simple fact of its survival against all the odds. And let us remember what the 'odds' have been: almost five decades of US economic sanctions—still in existence and now easily the longest sanctions in history, repeated crises, the collapse and disappearance of the Soviet Union and the rest of the Socialist Bloc in 1989-91, and finally the slow retirement of Fidel Castro between 2006 and 2008.I intended the book to go beyond the usual explanations–and, I think, somewhat hackneyed or clichéd explanations–i.e. that the survival of the Cuban Revolution is due to Soviet support, fierce repression, some sort of mindless popular loyalty to the charismatic authority of a single leader, and so on.

At best, those reasons can only explain part of the longevity. But for the most part they simply succeed in distorting our understanding. Above all, those explanations miss the enormous complexity of the political system which has been built up in Cuba since 1959.The book itself was actually based on my inaugural professorial lecture at the University of Nottingham in 2004. In that lecture, 'Reassessing the Cuban Revolution: past, present – and future', I managed to predict that Fidel Castro would stand down in 2009. I got the date wrong by one year, but, in my defence, Castro’s retirement was accelerated by a serious illness which no one foresaw. That prediction was based on my reading of the process of Revolution and the politics of Cuba—a reading which, I hope, has gone into this book.