Louis Kaplan

The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer

University of Minnesota Press

288 pages, 6 1/8 x 9 1/4 inches

ISBN 978 0816651573

ISBN 978 0816651566

The story of William Mumler and the birth of spirit photography offer one of the most fascinating and haunting chapters in the history of the medium. In the 1860s, this Boston engraver turned photographer claimed that he was capable of capturing the ghosts of the dearly departed for bereaved friends and relatives on glass plate negatives. In The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer, I have brought together Mumler’s haunting images, his revealing memoir, and rich primary sources, including newspaper articles and P. T. Barnum’s famous indictment of Mumler in his book Humbugs of the World. I also have contributed two extended essays, “Ghostly Developments” and “Spooked Theories.” The first one offers in-depth historical perspective of the Mumler phenomena as it delves into the socio-cultural issues surrounding this vivid ghost story. The second essay is a theoretical intervention in which I explore how concepts derived from psychoanalysis and deconstruction provide us with ways to understand the meaning and significance of Mumler’s spirit photography.

All in all, I have played the part of the medium in channeling Mumler’s voice for a contemporary audience. The result is this photographic ghost story. The Strange Case also contains numerous reproductions of Mumler’s photographs and many of these images are published here for the first time. In this context, I want to acknowledge the late art collector Samuel Wagstaff. Wagstaff had the foresight to buy spirit photographs well before they became fashionable, and he sold an album of thirty-nine Mumler images to the Getty Museum. That album forms the basis of the amazing images in my book.

The photographic phenomena of Mumler and the controversy surrounding him reached its climax in a dramatic trial in New York City in the spring of 1869. This was when Mumler was arrested on charges of larceny and swindling the public in a sting operation set up by the Mayor’s office. With testimony from such notables as P.T. Barnum (who claimed that he knew a “humbug” when he saw one) and the Wall Street banker Charles Livermore (a satisfied customer who was convinced that Mumler had summoned his dead wife), this sensational trial received extensive coverage in the newspapers and popular journals of the day. The book contains two chapters on “Mumler in the Press” – one covering the period of the birth of spirit photography and the other related to the year of the trial that includes many excerpts of witnesses’ testimony.

When asked whether he would be consulting with former Presidents, Obama answered that he would seek out only those who are still living. The implication being that there are not going to be any seances in his White House as was the case with the Reagans and the Clintons. However, if Obama would like to style himself as a true Lincolnian in his presidency, he ought to think again. Mary Todd was known to have Spiritualist seances in the White House and these would lead to her association with our photographic hero, William Mumler.

The Strange Case offers a different kind of ghost story. Instead of the usual fare of haunted houses and wandering apparitions, these are photographic encounters with spirit-forms appearing in the photographs of William Mumler. From a sociological perspective, one might think of these spirit photographic phenomena as constituting the urban legends haunting the major metropolitan centers of Boston and New York City in the 1860s and 1870s. Let us not forget that this was the historical period that witnessed the American Civil War and its aftermath. This factor has an important bearing upon Mumler’s story: the Civil War was a time of intense suffering and mourning in the American body politic. The American Civil War was also a period of high infant mortality rates. In promising the return of lost love ones through this relatively new photographic medium, spirit photography offered solace and consolation to the grieving nation and it assisted in the work of mourning for many people.

The other important historical context for understanding the rise of Mumler’s spirit photography has to be the growth of Spiritualism as a popular religious movement. This politically progressive Christian reform movement blossomed in the mid-nineteenth century in the United States under the leadership of the “Poughkeepsie Seer” Andrew Jackson Davis and it thrived on a culture of mediumship. The contested phenomena orchestrated by the Fox Sisters inaugurated Spiritualism in the spring of 1848 with incidents of “rappings” and “table turnings” in their haunted home in Hydesville, New York. It was claimed that these communicating and communicative spirits were making themselves known by means of “spiritual telegraphy” which might be viewed as an otherworldly type of Morse code. Let us recall that one of the founding tenets of Spiritualism was the belief that communication with the dead was possible and that spirit photography was a new phase in spirit communication and communion.

In this light, Mumler’s “spiritual photography,” as it was sometimes called, can be understood as another divinely inspired medium whereby the invisible ghosts revealed themselves to the living in the form of visual images. Around this same period, the use of double exposure as an artistic technique in the photography of Oskar Rejlander and the genre of stereoscopic cards featuring ghostly apparitions as photographic amusements illustrated that technical processes and darkroom manipulations could produce the same haunted effects. So while believers held that Mumler’s activities were wondrous occult phenomena and offered visual evidence of the truths of Spiritualism, doubting skeptics challenged these images as fraudulent tricks of double exposure and a swindle perpetrated upon a gullible public. To the unbelieving rationalist, the ghostly phenomena were of a mechanical rather than a supernatural order. In summary, Mumler’s story must be viewed as part of the larger crisis of faith that so characterized the second half of the nineteenth century and that still engages us at the beginning of the twenty-first, a crisis embodied in the conflicts between science and religion, evolution and creationism, rationality and faith.

But whether derided as a con man’s trick or hailed as a religious revelation, Mumler’s spirit photographs provided satisfied customers with the return of the dead. In this way, the spirit forms haunting the frames of these photographs literalize the meaning of the ghost as revenant, as something that returns to haunt us in the present. They foreground photography’s own intimate relationship with death or what Roland Barthes experienced in posing for the camera as a “micro-version of death,” the experience of “truly becoming a specter.” The iconography of death in nineteenth century visual culture owes much to photography as it provided both memento mori images of freshly mortified corpses and spirit photographs that purportedly summoned the return of the dead. We are indebted to William Mumler for initiating this peculiar iconography of death and death reanimated via the shady practice of spirit photography.

As a photographic historian and theorist with an abiding interest in the medium as both spectral and haunting, my desire to present the strange and singular case of William Mumler goes back a very long time. The idea for such a book is something that has haunted me in various guises, whether more commercial or more arcane. I am very pleased that it has finally taken shape in this form and format with the University of Minnesota Press.

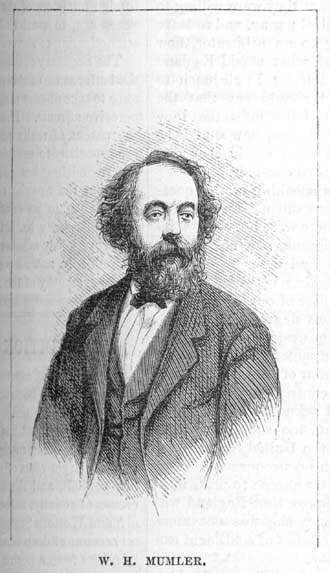

W.H. Mumler in Harpers Weekly, May 4, 1869

For a quick zoom, I refer the reader to Mumler’s most famous spirit photograph and to the passages where he recounts this strange visitation in his memoirs, The Personal Experiences of William Mumler in Spirit Photography (1875). This is the amazing image where the ghost of the assassinated president Abraham Lincoln comes back to give comfort to his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, who was an ardent Spiritualist throughout her life. One notices that the ghost of Honest Abe stands behind Mary Todd and that he even has his hands around her shoulders in a show of support and in a pose typical for many of Mumler’s ghostly images. The loving gesture and its haptic quality illustrates the affective power of these images to put people in touch with the dearly departed and to help them with the mourning process. One also notices that the ghost of their son Thaddeus appears on the left hand side of the image—Mary Todd received two spirits for the price of one.

As Mumler recounts and as the image shows, the former First Lady appeared to him as a “black widow” dressed in the garb of mourning and wearing a veil which she only removed for the photograph. Mumler also tells us that Mary Todd took the assumed name of Mrs. Lindall when she visited his Boston studio in 1872. Obviously, Mumler would like his readers to believe that here was a situation of strict anonymity and that there was no way that he could have known the identity of his sitter or her beloved ghost. Interestingly enough, the New York photographer Abraham Bogardus also took a photograph of P.T. Barnum with the ghost of Lincoln hovering over him and this was presented as evidence for the prosecution at the trial in 1869 to show that such spirit photographs could be produced by mechanical means. From the perspective of the skeptic, one is struck by Mumler’s audacity in taking advantage of the poor widow with his photographic magic tricks. From the perspective of the believer, one is struck by Mary Todd’s conviction that she was in the presence of a photographic miracle.

By the way, I find it uncanny that Barack Obama made a joke in the first press conference after his election as President of the United States that bears upon this close-up. When asked whether he would be consulting with former Presidents, Obama answered that he would seek out only those who are still living. The implication being that there are not going to be any seances in his White House as was the case with the Reagans and the Clintons. However, if Obama would like to style himself as a true Lincolnian in his presidency, he ought to think again. Mary Todd was known to have Spiritualist seances in the White House and these would lead to her association with our photographic hero, William Mumler.

Mumler’s story must be viewed as part of the larger crisis of faith that so characterized the second half of the nineteenth century and that still engages us at the beginning of the twenty-first.

What is it about Mumler’s story and the conjuring of these technological ghosts in photography that still resonates with us one hundred and fifty years later at the dawn of the digital era? The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer reminds us of the intense intertwining of the history of communications technologies with occult or paranormal phenomena in every generation. The “ghosts in the machine” can be found in every successive technological medium from telegraphy to television to cyberspace. Jeffrey Sconce has referred to this as haunted media. If you browse around the internet, you will find a wide range of popular examples of ghostly images produced by digital means as well as the same debates between skeptics and believers with the accusations of Photoshop manipulations on the one hand and the claims of New Age revelations on the other. But whether discussing Mumler or the ghost hunters of today, I take a more deconstructive approach, recalling how each side of the debate is always already haunted by and dependent upon the other. For me, it is not a question of affirming or debunking the truth claims of spirit photography. The point is rather to acknowledge spirit photography’s affective power and its ability to construct meaning and value as well as to provoke controversy and debate then and now.

This book illuminates a curious chapter in nineteenth century American history that has largely gone unnoticed even though it has major ramifications for many fields. First and foremost, the story of William Mumler and the birth of spirit photography highlight a fascinating chapter in the history of photography, deserving of its place in the canon. The book would appeal to history buffs of the American Civil War period because of the many renowned personages (often Mumler’s clients) who walk through its pages. It has major significance for religious studies in light of the way in which it implicates the history of Spiritualism. Mumler’s famous trial also raises interesting issues about the use of photographic evidence in a court of law and this makes the book quite relevant for legal studies. Given that the book elucidates Mumler’s case history through theories derived from psychoanalysis and deconstruction, it impacts and implicates these fields of study as well. Finally, I believe that everyone enjoys a good ghost story and I want us all to remember that, whether dead or alive, photography gives up the ghost.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!