David Livingstone

Adam’s Ancestors: Race, Religion and the Politics of Human Origins

Johns Hopkins University Press

320 pages, 6 x 9 inches

ISBN 978 0801888137

The idea that all human beings are descended from Adam has been a long-standing conviction in the West. Indeed it’s been a central doctrine among the monotheistic religions more generally. But running alongside this conventional understanding of our origins, there has been an alternative account. This account claims that there were human beings on earth before, or alongside, Adam, and, what’s more, that the descendents of those still occupy the planet. In this book I take up this story. It takes me way back to the Middle Ages – and, in the other direction, right up to the twenty-first century.

What I try to do is recount the twists and turns in this narrative of human beginnings, and show the astonishingly wide range of discourses in which it has been implicated. Initially this alternative account was used to bring critical scrutiny to the Bible and can be seen as a critical early move in the development of textual criticism. Creation stories from places as far apart as Egypt and the Americas, Babylonia and China, raised in some people’s minds the thought that the Hebrew scriptures might not be an entirely reliable source of information about beginnings. Not surprisingly the idea of human beings existing before Adam was widely rejected and castigated as heresy. Later it was incorporated into mainstream anthropology on both sides of the Atlantic in support of the contention that the human race had numerous separate points of origin. The idea here was that humanity was not descended from a single, common source, but rather emerged in a range of different original locations.

At the same time the idea that other human beings were on earth before or alongside Adam began to find its way into religious thinking as a tactic to reconcile science and religion. During the nineteenth century, it underwent two additional modulations. First, the coming of Darwinism encouraged some to consider the possibility that the human race evolved from pre-Adamic hominids. This means that the idea could be used to keep religion and the idea of human evolution in tandem. Second, it was incorporated into a virulent strain of scientific racism in Britain, and more especially in America. It was a belief that was easily used as a justification for racial segregation and slavery, and for opposing race-mixing. Shadows of the theory have continued to exert their influence right up to our own day. It has been resurrected, for example, as the basis for extreme versions of white supremacy—an altogether sinister retooling, by a deeply conservative community, of an idea originally used for radical and humanitarian purposes.

Adam’s Ancestors brings to the fore what I’d call the contingency of labeling. It’s interesting to me that an idea born in skepticism, nurtured in infidelity, and castigated as rank heresy, later resurfaced among the most conservative religious believers in their ongoing project to find rapprochement between religion and science.

The wider cultural landscape within which Adam’s Ancestors is located has a number of landmarks on its horizon. First, I see it as a contribution to the study of the relationship between science and religion. When we think of science and religion, I suspect that two or three critical moments – icons perhaps – spring to mind: the condemnation of Galileo by the Catholic Church in 1633, the legendary tussle between Bishop Samuel Wilberforce and Thomas Henry Huxley on Darwin’s idea of evolution in 1860, the Scopes monkey trial’ in 1925, and more recently the controversies over creationism and intelligent design. I want to widen the debate by advertising the persistent dialogue between science and religion over human beginnings and human identity.

Secondly, I hope the book reveals that there are critical social and political issues at stake in the project of elucidating human origins. I think this is the case just as much for modern scientific inquiry as for theological endeavour. The ways in which authoritative texts – particularly the Bible – were deployed for social and political purposes comes through fairly dramatically, I think, in the book. Sometimes these were benign, often they were malevolent; sometimes they gathered all humanity within a single embrace, at other times they excommunicated whole branches of the human species from the human family. Either way, genesis sagas are political declarations. And this is no less true of modern genetics. Time and again, in recent years, the findings of human geneticists hunting for humanity’s point of origin, and of palaeo-anthropologists with the same quarry, have been catapulted into the political arena. Their findings have been used to underwrite, or undermine, the idea of human unity – and thus, apparently – human equality.

Thirdly, I hope that Adam’s Ancestors brings to the fore what I’d call the contingency of labeling. It’s interesting to me that an idea born in skepticism, nurtured in infidelity, and castigated as rank heresy, later resurfaced among the most conservative religious believers in their ongoing project to find rapprochement between religion and science. Condemnation in one generation; benediction in another. It’s the same with what passes as science’ and religion.’ That boundary is differently marked in different settings. There simply is no hard and fast definition that is going to segregate one domain from the other. Numerous candidates have been offered of course. But once you begin to look at the historical record they simply do no real work. Intellectual boundaries, like national frontiers, are cultural constructions. So overall I hope the book will show the power of ideas and their persistence over centuries. But I hope it no less reveals how ideas are always located in particular settings, and that they are resources for cultural and political projects of many kinds.

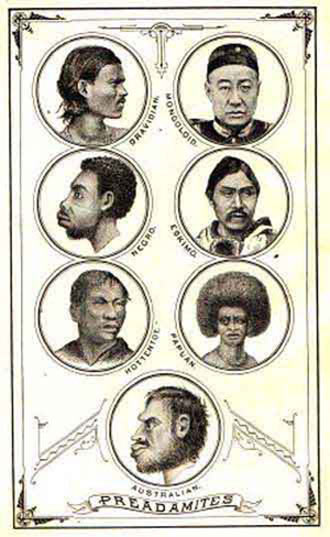

Adam’s Ancestors, page 189: The Frontispiece to Alexander Winchell’s Preadamites (1880)

There’s a rather quirky moment in the book which I hope might attract a casual reader’s eye. It’s important because I think it shows how powerful a perfectly absurd idea can be in the wrong hands. But it also shows the sinister depths to which a culture can descend in self-justification. The episode congregates around a number of efforts to identify what was the nature of Eve’s transgression in the Garden of Eden, the sin that supposedly set humankind off in the wrong direction. In 1875, one character set out to answer the question, 'Who Tempted Eve?’ His bizarre account is recorded in the section of the book called 'Eve’s seduction.’ Through a series of weird interpretative contortions, A. Hoyle Lester came to the conclusion that the 'serpent’ recorded in the Genesis account was actually a beast in human form – a black man – and that Eve’s downfall was in fact a sexual transgression, a gross inter-racial liaison from which was spawned a race of inferior beings. What’s amazing is that this idea actually caught on among those intent on bestializing whole sections of the human family.

How is this all part of my story? Well first it’s a further inflection on the idea that humanity composes different original human stocks which could give succour to those of a supremacist mindset. What’s interesting here too is the way that in later generations supremacists revisiting these nineteenth century absurdities fancify them with snatches of modern genetics so as to scientize their racist pamphleteering. Secondly, the episode reveals the power of origins stories – whether scientific or religious – to do ideological work. Genesis myths and genetics myths alike are not just accounts of beginnings, they are weapons in the arsenal of racial politics. Thirdly, it shows the remarkable persistence of a basic idea which can be mobilized for radically different purposes in different settings. When the idea of pre-Adamic humanity was originally put forward in the mid seventeenth century, the idea was that the Hebrew scriptures were exclusively an account of the Jews, and that all other people were of a different origin. But since, it was claimed, all humanity benefited from Israel’s Messiah, it was essentially humanitarian in impulse. By the later nineteenth century, the idea of non-Adamic humanity was being mobilized for the grossest forms of racial propaganda.

When the idea of pre-Adamic humanity was originally put forward in the mid seventeenth century, the idea was that the Hebrew scriptures were exclusively an account of the Jews, and that all other people were of a different origin. But since, it was claimed, all humanity benefited from Israel’s Messiah, it was essentially humanitarian in impulse. By the later nineteenth century, the idea of non-Adamic humanity was being mobilized for the grossest forms of racial propaganda.

In a sense I think of Adam’s Ancestors as a history of the underside of a number of modern concerns – anthropology, race relations, evolution, science and religion. The book excavates the genealogy of a tradition of thinking that the West now routinely ignores – or suppresses. In that sense it is a contribution to the understanding of the Enlightenment’s alter ego. But seeing it solely in that context would be a mistake. Some of the ideas whose archaeology I am unearthing may seem ludicrous or preposterous to modern eyes. But they were central to earlier ways of thinking about our origins and our identity and our destiny, and elucidating them is thus a history of the present. Indeed there are more or less distant echoes of many of the themes that circulate through these earlier debates in recent research on hominid pathways and the use of DNA to construct human genealogies. For these enterprises too are cultural projects serving political interests of one sort or another.

In a review of Adam’s Ancestors, the well-known historian and philosopher of science Michael Ruse judged that the book “informs and leaves you with more questions than when you started.” It would be a great source of satisfaction to me if that were to be the final judgment of every reader.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!