Ariella Azoulay teaches visual culture and contemporary philosophy at the Program for Culture and Interpretation, Bar Ilan University. She is curator and director of documentary films. She is also the author of Atto di Stato (Act of State, 2008, Bruno Mondadori, in Italian), Once Upon a Time: Photography following Walter Benjamin (2006, Bar Ilan University Press, in Hebrew), and Death’s Showcase (2001, MIT Press), which won the Affinity Award, International Center of Photography. She is co-author, with Adi Ophir, of This Regime which Is Not One: Occupation and Democracy between the Sea and the River (from 1967 onwards, Resling, in Hebrew).

The Civil Contract of Photography is about the relations between photography and citizenship in disaster contexts. The book proposes a historical and theoretical analysis of the relation between photography and citizenship, and in order to do that, I reread two moments in history: the French Revolution (1789) and the invention of photography (1839). The Civil Contract of Photography centers around the open-ended relations between photographers, photographed persons and spectators. The book analyzes the way in which, since the onset of photography in the mid-19th century, looking at photographs and making them speak have become a part of a civil practice.The political theory laid out in this book is founded upon a new conceptualization of citizenship as a framework of partnership and solidarity among those who are governed. It is a framework that is neither constituted nor circumscribed by the sovereign. The theory of photography proposed in the book is founded on a new ontological-political understanding of photography. The book takes into account all the participants in photographic acts, approaching the photograph (and its meaning) as an unintentional effect of the encounter between camera, photographer, photographed subject, and spectator. None of these participants in the photographic act has the capacity to seal off this effect and determine the photograph’s sole meaning.The civil contract of photography assumes that, at least in principle, the users of photography, possess a certain power to suspend the gesture of the sovereign power which seeks to totally dominate the relations between them as governed—governed into citizens and noncitizens, thus making disappear the violation of citizenship. This is an attempt to rethink the political space of governed populations and to reformulate the boundaries of citizenship as distinct from the nation and the market whose dual rationale constantly threatens to subjugate it.The book seeks to arouse two dormant dimensions of thinking about citizenship and to recast them as points of departure for a new discussion of this concept. The first of these dimensions consists in the fact that citizens are, first and foremost, governed. The nation-state creates a bond of identification between citizens and the state through a variety of ideological mechanisms, causing this fact to be forgotten. This, then, allows the state to divide the governed—partitioning off non-citizens from citizens—and to mobilize the privileged citizens against other groups of ruled subjects. An emphasis on the dimension of being governed allows a rethinking of the political sphere as a space of relations between the governed, whose political duty is first and foremost or at least also a duty toward one another, rather than toward the ruling power.

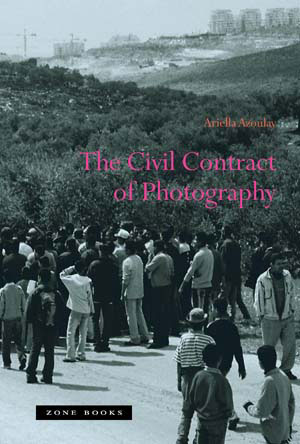

Ariella Azoulay The Civil Contract of Photography Zone Books600 pages, 6 x 9 inches ISBN 978 1890951887

We don't have paywalls. We don't sell your data. Please help to keep this running!