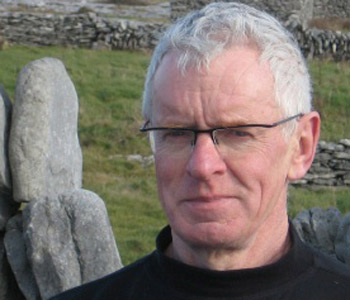

Robert Gildea

Children of the Revolution: The French, 1799—1914

Harvard University Press

530 pages, 6 1/4 x 9 1/4

ISBN: 978 0 674 03209 5

‘The bloody truth about France’ was the heading of the London Sunday Times review of this book. For those who think France is about camembert and surrender, here is another story. The French Revolution of 1789 plunged France into twenty-five years of civil war, religious war, Terror, dictatorship and continental war from which it took a century to recover. The ‘children of the Revolution’ are the successive generations of French men and women who were torn between resuming old battles they had lost and forging a strong and united French nation. They could not decide whether they wanted a Republic, a monarchy or an Empire, Napoleon-style: there were three revolutions and ten regime changes in seventy years. They struggled to regain the great-power status they lost at Waterloo, and looked enviously towards Britain, the United States, Russia and Germany. Defeat by Germany in 1870 plunged them again into civil war, but after that they found a political consensus around a middle-of-the-road republic and built an overseas empire, so that by the time Europe went to war in 1914 they were strong and united enough to withstand the onslaught.

Successive generations of French men and women could not decide whether they wanted a Republic, a monarchy or an Empire, Napoleon-style: there were three revolutions and ten regime changes in seventy years.

This is not just a political story, because that only tells part of what is fascinating about France in this period. What are the images we have of France in this period? The Paris of the boulevards built by Baron Haussmann in the 1850s and 1860s that was supposed to make it impossible for revolutionaries to throw up barricades, but which did not prevent the Paris Commune in 1871. The basilica of Sacré Coeur overlooks Paris, built by mass subscription among Catholics who sought God’s forgiveness for the Commune, which desecrated churches and ended in a bout of priest-killing. For France was in the grip of religious war as well as political strife, Catholics against Protestants, Catholics and Protestants against Jews in Alsace, Catholics against anticlericals, deists and atheists. It was a battle of who was to control the schools, the written word, even the state, and one that was not solved until the separation of Church and state in 1905.

We are familiar with the Eiffel tower, completed in 1889, which symbolised the arrival of France as an industrial power, although at the same time France remained a country of small towns and villages and the French preserved a nostalgia for slow-moving, rural life. We know of George Sand, who had to write under a man’s name, and of Marie Curie, who became a professor only after her husband was run over by a cab. This book explores the ways in which French women carved a role for themselves in the teeth of marital, professional and political discrimination. We know about Paris as a centre of global culture. Henry James fell out with Flaubert, Winaretta Singer the sewing-machine heiress married a French aristocrat and promoted Verlaine, Debussy and Stravinsky, while Gertrude Stein paid Picasso’s bills. But French culture was also for the masses: the novels of Jules Verne, music-hall star Yvette Guibert immortalised by Toulouse-Lautrec, the cinema of the Lumière brothers, and the Tour de France which brought villagers to their doorsteps. This is a book which gives a context to the icons, sets the unfamiliar alongside the familiar, proposes a fresh way of looking at a fascinating century of French history.

One of its techniques is to zoom in on particular people or places, then zoom out again to consider the wider picture. The chapter on the religious revival in France after the Revolution starts with the Curé d’Ars, a semi-literate priest who came to a god-forsaken parish near Lyon in 1818 and gradually brought it back to the faith. So great was his reputation that pilgrims came from far and wide and he had an eight-day waiting list for his confessional and he was proclaimed a saint in 1925. The first chapter on women begins with the story of a young woman whose inclination to follow her own ideas rather than social convention causes her to lose the man she loves, and with whom she is reconciled only in death. This is not a true story but the plot of an 1802 novel by Madame de Staël, Delphine. The book takes the slightly post-modern view that contemporary novels tell us as much about the way in which a society works as bureaucratic reports and economic statistics. Balzac describes ambitious lawyers, money-grabbing bankers, speculators and shopkeepers and land-hungry peasants rocking what he saw as traditional landed society, while Zola describes the same peasants fifty years later, the ruin of small shops by department stores and the growth of the industrial working class in Germinal.

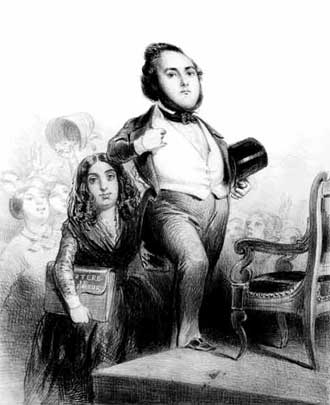

George Sand whispering instructions to the Interior Minister in 1848

The way in which the French related to the world outside is dealt with less as foreign policy than as ways in which French travellers discovered and commented on foreign countries and people. In the chapter ‘France in a foreign mirror’ you can see what the French thought of America: Chateaubriand, who went there in 1791, fantasised that it was still in a state of nature. Lafayette, who had fought alongside the Americans in the War of independence, returned there for a victory tour in 1824 and praised it as the land of liberty. The much younger Tocqueville came in 1831 and admired American democracy, but was also concerned that it might end of as ‘the tyranny of the majority’ and did not understand how the American passion for equality could allow slavery.

Alternatively, turn to chapter 8, ‘War and Commune, 1870-1871’. This describes the siege of Paris by German armies during which the population was reduced to living on elephants from the zoo and blackbirds, then rose against the government that wanted to surrender to the Germans, an insurrection that was put down with the loss of 20,000 lives.

Turn to the conclusion. This begins with the death at the battle of the Marne of poet and intellectual Charles Péguy. He had made his name during the Dreyfus Affair when the France of the rights of man locked horns with reactionary, anti-Semitic France. He represented the new France, republican, socialist, enlightened, but he also loved the Catholic faith, symbolised by the cathedral of Chartres, and French history, incarnate in Joan of Arc. He was killed, stupidly, standing up in his blue coat and red trousers, urging his men on. And yet he represented the coming together of many Frances which had so long been in conflict, in a patriotic gesture the like of which would see the country to victory in 1918.

Don’t miss the illustrations: sixteen plates and 43 images of celebrities staring from another era, following the shift from painting to photography. Paris as slum-land, imperial capital and battlefield, the social elite and striking workers, holidaymakers in Normandy and Louis Renault in one of his new cars.

The book takes the slightly post-modern view that contemporary novels tell us as much about the way in which a society works as bureaucratic reports and economic statistics.

The story comes to an end on the battlefields of northern France. The history of France in the twentieth century was not so happy. France was briefly occupied by Napoleon’s conquerors in 1815, and by the Germans in 1870-71, but was defeated and occupied for four years by the Germans of the Third Reich in 1940-44. The republic founded in 1870 was destroyed, the anti-Semitism that had flared up during the Dreyfus Affair ended up with the deportation of a large number of French and foreign Jews to the death camps. It took de Gaulle to drag France out of this mess, founding a republic in which the president had much greater power, and asserting France’s greatness by withdrawing the country from the military side of NATO.

Children of the Revolution is about a much more positive period in French history, when the French managed to combine ideological battle with political compromise, religious strife with toleration, artistic and literary genius with education and culture for the masses, gay Paris with a passion for the countryside, feminism with family life, national greatness a love of peace and the feeling that at least they did not have to work as hard as the British.

If you are fed up with yet another book on Hitler or Stalin, the Russian Revolution or Nazi Germany, this will make a refreshing change.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!