Tyler Volk

CO2 Rising: The World’s Greatest Environmental Challenge

MIT Press

264 pages, 5 3/8 x 8 inches

ISBN: 978 0 262 22083 5

When fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas are combusted they release CO2. This greenhouse gas is no ordinary pollutant but an inherent waste byproduct of the energy conversion. The CO2 is ejected skyward, thereby letting loose carbon atoms that had been outside the biosphere “system” for hundred of millions of years during their deep, underground sequestration. Now released and wafted worldwide, the waste carbon then infiltrates into all parts of this surface system we inhabit—the biosphere’s intricate and intimate circulating webs of air, water, and soil, which include myriads of living creatures. In short, the newly created CO2 enters the global carbon cycle. This Jackson Pollack-like complex carbon cycle is one of the great wonders of the universe. We are privileged to live within it and we must come to know it to understand the profound changes that are unfolding today.

The goal of this book is to set forth in plain language and powerful images the essential facts about the dynamics of fossil fuel-derived CO2 in the carbon cycle, how the CO2 is changing the natural world, how it will affect climate, and how its creation is tied to human material well-being. The result, I hope, is the definitive statement about such topics as: How do we know the CO2 rise is due to human activities? What will be the future amounts of CO2? What causes the extraordinary seasonal cycle of CO2? Why don’t the oceans remove all the CO2? What do we learn from the dynamics of carbon in Earth’s past ice ages? Why are the exhaled breaths of the growing human population not net additions to atmospheric CO2? How ready for massive deployment are various energy technologies that do not emit CO2, for example carbon sequestration, biomass, solar, wind, and nuclear?

Written by a carbon cycle scientist, my book illuminates the complex, awesome dynamics of the carbon atom. I have attempted to put forth the essential facts that I believe every Earth citizen should know about the role of fossil fuel carbon in the imbalance that we have created in the cycles. The book links the CO2 molecule to life, energy, and the future of civilization.

When you go to a doctor and the doctor gives you information about your body, <em id="">the doctor makes a crucial assumption</em>: Even though you are not a medical expert you do know the basics about how your body’s organs work. The heart pumps blood, the lungs pump air, the brain thinks, the liver filters. But I have found that few possess the equivalent level of understanding about the 'organs' of the planetary physiology and the globe-connecting metabolic pathways that go in and out, to and fro, among the oceans, soils, air, and all living things.

When you go to a doctor and the doctor gives you information about your body, the doctor makes a crucial assumption: Even though you are not a medical expert you do know the basics about how your body’s organs work. The heart pumps blood, the lungs pump air, the brain thinks, the liver filters. But I have found that few possess the equivalent level of understanding about the “organs” of the planetary physiology and the globe-connecting metabolic pathways that go in and out, to and fro, among the oceans, soils, air, and all living things.

Perhaps what gives CO2 within the carbon cycle the power to serve a great entry point into a systems view of global warming and issues about the human future is the simple fact that carbon is material. Carbon can be made tangible to the mind as it moves among the organs of the biosphere. Our bodies are made of carbon. So are the trees. Carbon is in the ocean and used by the myriads of tiny green plankton. Carbon is definitely the “heart” of biological molecules, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and DNA. I have found that when people learn about the fascinating global web of the carbon cycle and then see how huge has been the human-induced change in the atmosphere’s CO2, then related issues become much more salient and easier to get across: how the greenhouse effect works, why sea level will rise, why summer crops might dry out, why ecosystems will have to be managed to make the transition to a new climate, and why we need to re-think our energy systems as the global economy develops at 3 percent per year via what I call the global industrial growth automaton, for short, GIGA.

In offering this book, I wear two hats. The first is that of a scientist. The second is that of motivated writer. In addition to my work over several decades as researcher and educator, I am also a person dismayed that technological society has become addicted to the fossil fuel drugs. It is highly likely that the GIGA will keep on its seemingly inexorable path, sending the CO2 higher and higher until climate change reaches future stages that are unacceptable and virtually irreversible.

There is only one atmosphere, and we all, more or less, contribute to its chemical state. I try and let the facts about the conditions speak for themselves. I try to avoid any temptation for hysterics or distortions. The facts themselves lead me to conclude that we do have time to make the changes, but that they will be difficult because of the scales involved. Almost counter-intuitively, quite different but still reasonable possibilities for emissions make relatively small differences in atmospheric CO2 by 2050. The technological momentum inherent in each of those possibilities, however, make huge differences in the decades after that. Overall, we have not yet provided ourselves with enough options.

But there is also room for celebration, because the carbon cycle is one of the wonders of the universe, as worthy of careful exposition for the general public as any of the discoveries of astrophysics or brain science. One of my goals is to make the carbon cycle as real as your eating and breathing.

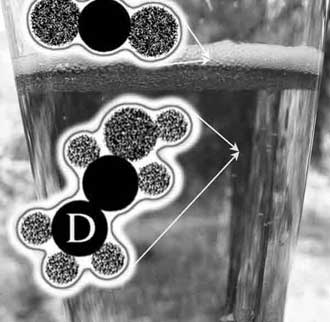

The carbon atom “Dave” (marked “D”) in a molecule of alcohol in a glass of beer. Also shown is a CO2 molecule in the bubbles near the top.

Named after Charles David Keeling, a distinguished carbon-cycle scientist, the carbon atom Dave serves, I hope, as a literary device that aids in revealing the fascinating paths that actual carbon atoms take during their global circuits. Through carbon atom Dave I present the carbon cycle from a carbon atom’s point of view. Each chapter includes a vignette from the life of Dave. These vignettes relate to the substantive technical content that follows. In the first several chapters, for example, Dave’s presence in an alcohol molecule in a glass of beer illustrates how a loop in the global carbon cycle works. His passage through a gas analyzer in the early 1960s leads to the topic of the discovery of the worldwide rise of CO2. Dave’s transit from the atmosphere into the ocean shows that circuits extend from plants to soils to air to water and back.

I was not able to introduce everything I wanted to by following a single atom of carbon. Dave, for example, entered the biosphere naturally—from the dissolution of a crystal in a limestone cliff during the last Ice Age. Some of the pathways in this book had to come from carbon atoms brought into the biosphere by the combustion of fossil fuels. Thus, I bring in several other atoms: Coalleen, Oiliver, Methaniel. By tracing the stories of these atoms, we appraise the magnitudes of various carbon fluxes to and from the atmosphere and the stability (or lack thereof) of the global carbon cycle in the past.

With the twin purposes of enhancing the enjoyment of our being alive as carbon-dependent organic beings and preparing the way for the later chapters, I planned the chapters in the first half of the book as relatively short primers on carbon fluxes that circulate among the great carbon-containing “bowls” of the biosphere. In the later chapters, I unfold the issues that are so challenging with respect to the future. These chapters, too, include episodes from the lives of my named carbon atoms—for instance, Oiliver and Methaniel are released from a burning stick used to cook a school lunch in Rwanda, and Dave passes through a wind turbine. But the material in the later chapters is denser, and the tone more impending as we project CO2 emissions into the future.

There are difficult issues that go beyond any debate, say, about a few wind turbines offshore of Cape Cod. What would massive deployment look like for new kinds of energy? [...] Can a new paradigm for economic wealth be set in place by 2050?

The debates about the global environment, warming, fossil fuels, new energy systems, and global equity are coming on strong and I try and bring readers face to face with all these vital topics. I hope that readers will gain an expanded vision into the future. They will start thinking about and visualizing the world situation fifty years ahead. They will become concerned about the future in a way that I truly believe they should be. They will come to see the world system differently, more interconnected, and know how their local actions and lifestyles have global consequences.

A major part of the book’s most significant message, I offer, is its examination of relationships among wealth, energy use, and CO2 emissions. CO2 emissions are tied to the present and most likely near-term trends in the global economy. It is possible to show, therefore, why CO2 will continue to rise and at what rate, given world energy policy, and what the uncertainties are given what we know about the carbon cycle. Slowing the rise will necessitate further development of sources of energy that do not emit CO2, such as carbon sequestration, solar, wind, nuclear, and others, all potential answers to the gamble about whether alternatives could be in place in time. There are difficult issues that go beyond any debate, say, about a few wind turbines offshore of Cape Cod. What would massive deployment look like for new kinds of energy?

I as well as many others believe that in the intensifying debates about the global environment, climate warming, fossil fuels, and new energy systems, we will eventually confront the issue of global equity on a per capita basis. The emissions of CO2 waste spread globally no matter where those emissions originated. So the economic “haves” are giving not only themselves the increased greenhouse effect. They also are giving it to the “have-nots.”

Will the U.S. in the year 2050, for example, still have per person emissions that are hundreds of percent points above the world averages, and thus continue to serve as the supreme example of wealth through CO2 emissions? Will the world even have an example of a complex, economically developed society that has low emissions? The economic machine will probably roll on pretty much like it has been, at least for the global total, as developing countries increase their emissions. After 2050 the gamble that the developed portion of humanity is taking with the state of the world and its capabilities to deploy options becomes much more serious. But what will the U.S. and other heavy per capita emitters do? Can a new paradigm for economic wealth be set in place by 2050?

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!