Music, Math, and Mind is written for musicians and music lovers, and will take them through a journey that uncovers the science of music and sound. Because artists and art lovers rarely have a good familiarity in math beyond multiplication, and even less in physics and biology, the book finds ways to make even difficult concepts in physics completely understandable with only grade school level math. Indeed, by the end of the first chapter, readers can derive their own musical scale. This is not meant to be a typical popular science book of short anecdotes to read in an afternoon at the beach, but a book that readers come back to for a long time, each time understanding more.

The book tackles some basic questions on math, physics, and the nervous system that are not discussed in music theory classes: Which sounds are in-and out-of-tune? Is it true that scales are really never in tune? What are overtones and harmonic sounds? Sound is formed from air waves that move in space and time. What shapes are these sounds, how big, fast, and heavy? How are sound waves different in air, under water or in the earth? Why do voices and instruments sound different from each other? Why do larger instruments play lower pitches? We have only two eardrums and two ears, how can we identify many simultaneous sounds in a band or in conversations (the “cocktail party problem”)? Are there mathematical definitions of noise and consonance? How does the brain understand what it is listening to? How are emotions carried by music? How do other animals hear and make sound differently than us?

If these issues are not taught to musicians and music lovers, it is not from lack of curiosity. Artists have of plenty of that, and this book is for them.

There are more styles of human music than there are human societies. But underlying all of them, even paleolithic styles, which can be deduced from surviving instruments in caves made from mammoth tusks, is an ancient and direct line of study that was initiated by natural philosophers in China, India, Egypt, and Greece. Their discoveries underpin the creation and comprehension of music, but are unknown to almost all musicians, as their training, understandably, has always been focused on learning the skills required to help earn a living.

But the questions of, for example, why there are musical scales, how instruments work, and the operation of the ear and auditory nervous system, underlie all music extending back to prehistory, and in many cases, throughout the animal kingdom. Indeed, one of the chapters is on music made and listened to by non-human animals. One surprising message is that the nervous systems of animals that seem very distant to us work very similarly to ours. For example, the cortex of the ferret reacts specifically to different human spoken phonemes, such as the sound of “th” or “f”, although this can’t be an important aspect of their evolution. The brains of songbirds and frogs and some insects react very similarly to some features of music, such as consonance and dissonance, and they likely interpret some music in ways that are much closer to ours than we suspect. On the other hand, some animals have extremely different sensory systems, and it is possible that the equivalent music or auditory communication in some moths are carried by the vibrations of leaves, a form of sound hard for us to imagine, or for some fish and bees, by electrical impulses, a sense that may be even more of a challenge to us to relate to.

While some of the topics covered on the book are very ancient (for example, the ways that we use rhythm and syncopation in music), some are extremely current and are undergoing rapid shifts. This book covers essential questions; each chapter starts with these sorts of simple questions, and does its best to address them, and to outline what we do or do not know. At the end of each chapter is a listening section that outlines music that extends these discussions. Most of these listening examples will be unknown to most readers, even professional musicians.

Some of the examples are from my own projects in both experimental science and art. For example, in the Introduction, where I discuss issues of training or self-taught approaches to making music, I suggest records I produced of young children creating and performing their own pieces in Brooklyn, Conkary in Guinea (a remarkable school run by the jazz saxophonist Sylvain Leroux), the mountains of Guatemala, and New York’s Harlem, in addition to English children coached by one of the pioneers of electronic music, Daphne Oram. In the chapter on the parameters of sound, I refer to recordings of the highest and lowest pitch singers and instruments, and my composition The Most Unwanted Song, written following a survey of the most disliked qualities in music. A chapter on the mathematics of rhythm refers to recordings of ancient Greek, ancient Arabic, flamenco, and Bach’s music, as well as my experiments with fractal canons. The chapter on animal music features many natural sounds, including the justifiably famous recordings of humpback whale songs and my construction of instruments for songbirds and for the Thai Elephant Orchestra, a group of 14 elephants in northern Thailand who have recorded 3 full length CDs.

Much of this book is based on a class I gave at Columbia University. It is taken by a very wide range of students, including freshman, and art majors to engineering majors and medical students, even professors. I needed to find ways to explain these concepts to all of them. Notably, professionally trained musicians who have taken my class knew virtually none of the material: it simply is not taught in conservatories and art and music programs. This knowledge might however deepen their creative possibilities and the understanding of artists and art lovers.

Perhaps the best way for a reader to begin is to peruse the questions that start each chapter and find ones that are of interest to them. The answers can be complicated—indeed some have been addressed throughout history—but no one should be intimidated. With some patience, the explanations are understandable by virtually anyone.

Here is an example: most readers have heard of “brainwaves”, but likely have no idea of what this term really means. In the chapter on brainwaves, we build on the previous chapter on rhythm in music, where we drew the conclusion that syncopation requires more than one “clock” of beats at a time, so we must have a means by which we can hold multiple clocks at once.

To understand how this is accomplished, we relate how the cells of the brain communicate with each other through “synapses”. To do this, they modulate each other’s electrical currents, and we describe how the cells of the brain, the neurons, act as batteries. But what is a battery? To understand that, we need to comprehend what voltage and current mean. We derive this using nothing more than multiplication and division by discussing how a bathtub fills with water from a water tower. (This last effort took me about two solid days to figure out for myself. But I explain it in two pages.)

From there we go through the history of the debate about whether animals produce electricity, which was partly settled by a study of the electric fish in the 1700s and later by experiments by Luigi Galvani, in which he stimulated a frog leg with electricity from lightning—a scientific paper published in 1791 that led to Mary Shelley’s book, Frankenstein.

From there, we discuss how a German doctor in 1929 recorded brain waves in humans by embedding recording electrodes under the scalps of his own children and discovered the alpha wave when he asked them to perform hard math problems, like dividing 196 by 7, in their heads.

We then discuss the nervous system rhythm with which we are most familiar, our heartbeat, and how the electrical currents that control the heartbeat are due to “channels” in the membrane that allow charged ions of sodium, potassium, and calcium to move back and forth inside and out from the cells. That allows us to move on to how the much faster rhythms in the central nervous system are activated by the same sorts of mechanisms. Finally, we get to how the connections between these different neurons can lead to the production of rhythms in the brain, while acknowledging gaps in present knowledge on these questions.

For listening material, we discuss the unnaturally rapid rhythms in electronic styles made on a laptop computer, Gene Wilder and Mel Brook’s Young Frankenstein, and the use of brainwaves to trigger music including my own record, The Brainwave Music Project, in which the computer musician Brad Garton and I enable jazz and classical performers to perform live duets with their own brain activity. In order to disturb one’s own expectations and drive interruptions that cause a cortical phenomenon known as “auditory evoked potentials” I advise readers to listen to anything by Spike Jones and His City Slickers. Really, anything by them.

In the Introduction, I write “no one needs this book”, as artists create great work without understanding the universal and physical bases of what they do. Yet artists and art lovers have imaginations that allow them to enter new territories and make the ones they already work in more profound. This book will help them further appreciate their own nervous systems, the intelligence of other species, and the nature of the cosmos—this might seem over the top, but as readers will come to appreciate, a great deal of what humanity learned in these topics genuinely comes from the investigation of music.

As much as I hope that this learning will help creative readers develop new work, and help listeners develop their appreciation, I think that there are a series of profound lessons in how these investigations broaden our horizons and insights.

For example, there is a controversial hypothesis from Gordon Shaw’s “Mozart effect”, in which he theorized that children would be smarter if they listened and learned to play Mozart, and that this can be used in the treatment of childhood epilepsy. In some studies, the decrease in seizure activity lasted beyond the duration of the music, suggesting that such music may be therapeutic. While the evidence is unclear, we have traced how sound and music travels to the cortex to modulate its synaptic activity, and in that way, playing a sound is analogous to a stimulating electrode in the deep brain.

Our understanding of wave theory, which underlies all contemporary electronics, in part came from the development of the siren, as in a police siren, which was originally a musical instrument invented by a Scottish physicist, John Robison (1739-1805), and further improved by Charles de la Tour (1819), who named it for the mythical Greek singing legends. The study of these soundwaves led to the discovery by Christian Doppler of the Doppler effect, which explains how siren pitches rise and fall. Albert Einstein extended Doppler’s insight in 1905 to describe how light travels at a constant velocity. The wavelength emitted from stars also stretches or compresses, and Edwin Hubble (1889-1953), extended this by noting that the most distant galaxies appeared red, suggesting that the “red shift” was due to the galaxies moving away from us, and so introduced the theory that we live in an expanding universe.

For the future, I suspect that some of humanity’s most important work will be in understanding other life. In this way, Roger Payne and colleague’s discovery of whale song, I think to some extent, helped to save them from extinction by our species. Recently, the primatologist Susan Savage-Rumbaugh with the musician Peter Gabriel showed that bonobos can improvise music, and Richard Lair and I showed the same with elephants. Perhaps the understanding of the art of other species will help us commit to treating them better and find ways by which they can survive the greed, thoughtlessness, and predation of our species.

And they will respond by lending insight into ourselves. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, Itai Roffman, and others in their field are now writing convincing arguments that some of these species should be legally treated as human beings, with the same rights to survive and prosper. I suspect that the more we know, the more we will agree with them, and the richer our relationship with nature will be. In my opinion, this is the essence of spirituality and the most essential goal for all us. There is much to do…

Art for all species!

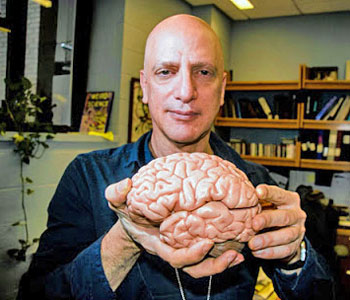

David Sulzer, known in the musical world as Dave Soldier, is a professor of neuroscience at Columbia University, who leads a double life as a composer and performer.