My book reconsiders the history of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) since 1949 from a novel perspective: the spread of consumerism in a self-proclaimed communist country.

The book title, Unending Capitalism, suggests my interpretation: The Chinese Communist Party’s Revolution aimed to end capitalism but instead accelerated its development. To use a term of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the party “negated” its Communist Revolution by expanding rather than ending capitalism. In my view, the CCP’s self-defined socialist state was not an antithesis to capitalism but rather a moving point on a spectrum of state-to-private control of industrial capitalism.

By examining the spread of consumer products and impacts on everyday life, I argue that the People’s Republic of China was a country closer to the “state capitalist” end of a spectrum of capitalism. This spectrum ranges from a capitalism entirely dominated by the state to one entirely dominated by the private sector. In my interpretation, all countries are on a spectrum of capitalism because all countries, including the PRC, have continually shifted their policies regarding the ownership of capital—sometime public, sometime private—and the allocation of resources—sometimes with greater state planning, other times by using markets.

I make my case with sources focusing on everyday life, using everything from blogs and newspaper clippings to internal government reports and archival documents. These sources reveal what “socialist” policies looked like from the bottom up rather than from the stated intentions of policy elites down.

I document unending capitalism through the spread of consumerism and all the inequalities accompanying consumerism with numerous examples. Take wristwatch production and distribution. In the early 1950s, after decades of relying on imports, China began to produce its own brands of wristwatches. Who got those watches first and why? What does the distribution of those watches say about the priorities of the state? In my analysis, facilitating the expansion of capital—even at the expense of socialist egalitarianism—was always more important. The state allocated those watches to those thought best able to help expand capital, not “build socialism”: managers rather than workers, people in factories rather than on farms, and those living in the prosperous coastal areas rather than the poorer interior. The same distribution priorities of capitalism everywhere with the minor difference of the managers being state employees rather than private businesspeople.

In short, the actual policies introduced and elaborated by the Communist Party manifested the forms of social and economic inequalities associated with capitalism, not socialism.

At the heart of Unending Capitalism (and my two other books) is the concept of consumerism. Consumerism—especially compared to identity, race, ethnicity, gender, and class—is underappreciated as a driving force for understanding the twentieth-century world and since, and not just China.

At the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, China was not mass producing or mass consuming much. But that changed fast. China began to mass produce goods, the lifeblood of industrial consumerism. As China industrialized, consumerism expanded.

China was also under constant assault from foreign powers. As a latecomer to industrial capitalism, China needed to overcome its relative backwardness as fast as possible with state-led industrial capitalism, or “state capitalism.” Communist Party leaders felt they could not simply rely on markets and private capital to industrialize fast. The state had to set priorities rather than have markets allocate scarce resources.

The state not only prioritized what the country produced but also what and how it consumed. State consumerism is my term to describe the state involvement in all three aspects of consumerism: what got produced and who got it; the ideas associated with mass produced products; and how possession of those things began to define people’s identities. People began to want specific branded products to communicate that they were a rich farmer, a powerful cadre, a successful manager, an intellectual, a city-dweller, or someone who knew how to work the system. My sources show, for instance, that by the late 1960s, there was an elaborate social hierarchy of local, national, and international brands of wristwatches.

In the early years of the PRC, the state was more desperate to maximize labor and minimize consumer desires. However, the state sometimes needed the population to consume. Even in the austere 1950s, as I show in the book, the state promoted Soviet clothing and fashions. And, as China successfully industrialized, it also promoted consumption of other items as an inducement to work harder. The losers were the same losers they always have been with industrial capitalism everywhere: rural farmers, women, manual laborers, minorities, and so on. And the winners were those in cities, working in state factories, and those working with their heads rather than their hands.

The contradiction between socialist words that sounded egalitarian and capitalist policies that led to inequalities was not lost on the population. My sources told me to doubt the state’s definition of China as “socialist.” So, I go beyond esoteric debates over what is “capitalism” and “socialism” to involve the people living in these countries and how they think. We often assume that people thought whatever the CCP was up to was “socialism” because state sources insist on it—and some of the winners such as those who got the first wristwatches believed it to be so. Instead, I follow my sources and focus on pervasive doubts across the entire society, from Mao Zedong on down, over what the Communist Party was actually building: a state-led version of capitalism, not the socialism of its claims.

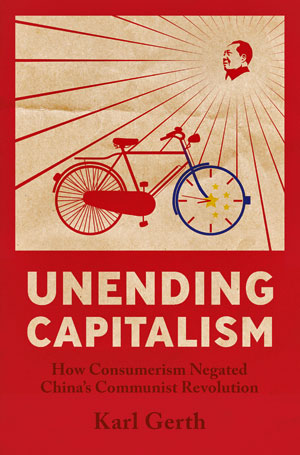

My book invites readers to contemplate the larger significance of easily overlooked mass produced things. If they were to skim the book, they would encounter dozens of photos and illustrations of such things. I use these images to provide an accessible entry point into the arguments of the book.

For instance, I include photographs of people wearing wristwatches and an illustration of someone on a bicycle. Such illustrations showcase the spread of consumer desires for industrially produced consumer products and document how the state both deliberately and inadvertently contributed to building consumerism and negating the Communist Revolution. After all, not everyone was able to obtain the three most sought-after items of a wristwatch, bicycle, and sewing machine at the same time. The distribution of these things created and reinforced the inequalities associated with industrial capitalism. Conveniently for the researcher, these sources were easy to find. People remembered their acquisition—or not—of these things even more clearly than more high-profile national events in the era.

I also include many photographs of Mao badges because China experienced the largest consumer fad in history when the country produced billions of badges of Chairman Mao for people to wear over their hearts during the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s. The badges were produced in thousands of varieties, sizes, images, and materials. The assortment depicted above includes a glow-in-the-dark badge in the lower right as well as, above it, Mao looking right, a potentially risky image for the maker for suggesting Mao was endorsing right-wing politics. Who got the latest, biggest, and most desirable badges reflected the growing material inequalities accompanying industrial capitalism. I use these images to illustrate the three defining aspects of a spreading consumerism: the unprecedented scale of industrial production of consumer products, the spread of discourse about such products in mass media that taught people to have new needs and wants, and the growing use of products, including badges, to create and communicate different, often hierarchical, identities. Even Mao and Zhou Enlai saw the badge fad as creating the opposite social values from the socialist ones intended.

I have no doubt that many also felt they were demonstrating loyalty to Mao and faith in the Revolution. But their action (using badges as a substitute currency, collecting them to demonstrate connoisseurship and connection, and countless other uses) had a larger impact. The badge fad—and indeed most activities associated with the Cultural Revolution such as house ransacking and student travel throughout the country—facilitated the “negation” of the Communist Revolution by expanding desire to use mass produced products for social differentiation. So, the badge fad helped manifest the expanding inequalities of industrial capitalism.

These are just two examples of the many aspects of consumerism illuminated by the illustrations. I also include advertisements from the era because few associate advertising and other forms of product promotion with “Maoist China.” And I do the same by highlighting periodic state promotion of clothing fashions. Likewise, I included photos of department stores and service workers to discuss how consumerism operated in retailing. Though such commonplace topics, seldom included in standard histories of the Mao era, we can reconsider the larger history of the era.

I hope my book helps readers reexamine a familiar history of China, and indeed the world since the Second World War. In my book, many famous events such as the Mao badge fad take on different meanings. In doing so, I invite readers to reconsider the history of capitalism through its relationship to consumerism.

My analysis suggests an ongoing need to move past Cold War-era binaries—a world we still imagine was divided between planned economy vs. free markets, dictatorship vs. democracy, interests of the collective vs. freedom of the individual, and public vs. private enterprise. Unending Capitalism suggests that these dichotomies may have become so politicized and inaccurate that they hide more than they reveal.

What emerges is a state capitalism that shifted back and forth along various points on a state-to-private spectrum of industrial capitalism, each permutation affecting consumerism in a different way. During the late 1950s and late 1960s, the political economy moved in the direction of state-controlled accumulation, whereas during the early 1950s, early 1960s, and 1970s the political economy shifted toward market-mediated accumulation and consumerism. These shifts were justified as a necessary part of Communist Party efforts to “build socialism” in order to reach communism. But the existence of such shifts reveals that neither the state’s vision of socialism nor its practice of state capitalism and consumerism were static.

Demonstrating that the terms state capitalism and state consumerism refer not to a fixed but rather to a fluctuating point on the state-to-private spectrum of industrial capitalism provides a reminder that all economies mix elements of institutional arrangements associated with both ends of the spectrum. All forms of industrial capitalism involve attempts to manage consumer desires.

Viewed from this perspective, the “market reforms” since the death of Mao in 1976 that promoted greater consumerism in China appear to be less of a break with Maoist ideology and policy and more as yet another shift in state-led capitalism. Such shifts also suggest that, aside from state capitalism and private capitalism, there are other varieties of capitalism in between these extremes.

I hope that expanding the study of the varieties of capitalism to include “socialist” countries such as China presents an opportunity to render the history of capitalism and consumerism as more truly global, and to think of the Mao era as part of an integrated world history rather than an isolated and exotic “socialist” interlude.

Karl Gerth is Professor of History and Hsiu Endowed Chair in Chinese Studies at the University of California, San Diego. In addition to Unending Capitalism, he is also the author of As China Goes, So Goes the World, which explores whether Chinese consumers can rescue the global economy without exacerbating global problems, and China Made, a history of economic nationalism in China. After receiving his PhD from Harvard in 2000, he taught at the University of South Carolina, Oxford University, and moved to the University of California—San Diego in 2013.