We see more and more disasters in the news every day. It is getting to the point where, with the exception of the current COVID-19 pandemic, major record-setting disasters barely make the news cycle for more than a few days. And despite billions in investments to prevent, prepare for, respond to and recover from disasters, the report card for preparedness is mixed at best.

As we learn more about disasters, we begin to see complexities upon complexities. Disasters are the culmination of a mosaic of factors from the built environment, politics, social structures, ecological dynamics, to culture, and social psychological factors. They are created, managed and burdened through an uncoordinated symphony of stakeholders that all contribute to our societal resilience, whether they know it or not.

And yet, we aren’t built to look at the whole picture. We specialize in various areas of expertise, and focus on the most recent disaster in memory. But the trajectory of societal development is increasing our vulnerability to disasters, as well as to the overarching threats themselves.

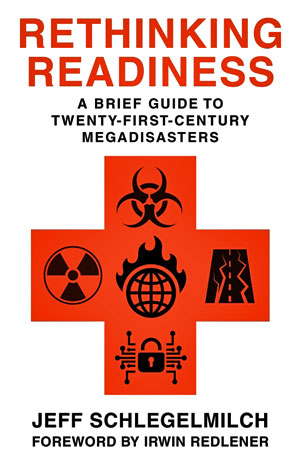

This book guides the reader through five looming areas of megadisasters where human activity is contributing to both the threat and the vulnerability. Through the topics of biothreats (including pandemics), climate change, critical infrastructure failure, cyber threats, and nuclear conflict, the nature and potential of these megadisasters is foretold. Commentary from experts in the field who have dedicated their efforts to mitigating these disasters helps to add more context to the scenarios in each chapter. The final chapters look at the cross-cutting themes, and start to illuminate the way ahead, to break the cycle of contributing to these threats and vulnerabilities.

This book should be seen as a primer on this topic. It is a slim volume providing an overview as a launching pad for deeper analysis and understanding. This book is not exhaustive in all of the disaster types we face, and indeed, there are many more that could have been included. Nor can it possibly identify all of the steps to take for readiness in the face of such complexity. But it does offer approaches to build our capacity for managing uncertainty, and for better integrating resilience into our thinking.

When I first endeavored to write this book, I was thinking about what I would tell an elected official who asked what they needed to know about disasters. Or if a professor was teaching a course in sustainable development or public policy, and wanted to do a unit on disasters, what kind of primer would provide the necessary information without getting too technical, or too lengthy, but also not be over-simplified.

The main objective of the book is to bring together expertise from different fields and different scholars to provide a holistic understanding of disasters, and then to work towards more dynamic solutions that embrace uncertainty and complexity. Some of the proposed approaches are drawn from the private sector and the business world, others from the military. So while our disasters are driven by an increasingly complicated world, our solutions can build on this by drawing together expertise from a multitude of scientific fields, other sectors of society, and communities by engaging in more meaningful ways to build resilience that is a fair match to the challenges we face.

When we focus on economic policy, the way we do business can increase the threat of climate change and build our infrastructure in vulnerable areas, or it can nudge growth to be more resilient and less toxic to the environment. When social policy increases distrust in government, it impacts our ability to effectively communicate protective actions to the public. But when it engages communities, it creates new channels for communication. When we build emergency management systems focused on consequence management, we miss opportunities to build resilience in policies that set the stage for disasters long before they ever occur. When we focus on the whole community, new resources and partnerships become available. And without proper research into these complexities, we end up with partial evidence, then fill in the gaps with what sounds right rather than what has been discovered to be effective. Whereas with evidence, we can replicate successes and avoid repeating mistakes in our efforts.

This theme of complexity and collaboration extends to the development of this book. Nothing in this book is solely my expertise. This book itself was a shared idea that originated with my friend, colleague and mentor, Dr. Irwin Redlener. Each chapter is made stronger by the commentary from other experts in the field lending their time and expertise to the narrative of the book, as well as some brilliant students and other close colleagues who provided inputs into the early versions of the manuscript. And with nearly 300 citations, as well as the input from peer reviewers and editors, the intellectual wells that I drew from are as broad and as deep as the topics discussed. This is all to say that I am incredibly fortunate to be surrounded by so many smart, dedicated and generous people, and that no understanding of disasters is possible through a single lens or by a single person.

I feel like I should say that the chapter I would want people to read if they picked the book up in the store and opened it up to a random page is the chapter on cross-cutting threats and vulnerabilities, or the conclusions. This is where all of the lessons from the various scenarios come together. Or maybe the preface that links the book’s themes to the current COVID-19 pandemic. But my actual answer is the chapter on nuclear conflict.

The chapter on nuclear conflicts was one that Dr. Redlener felt was particularly important, because the threat of nuclear conflict did not end with the cold war, and in some ways has gotten worse. But, paradoxically, the nature of the threats today may make it more survivable than in the past.

I also found myself learning more and more about this topic due to an increasing number of inquiries I was receiving on the old fallout shelter signs around New York City, and elsewhere in the country. These inquiries usually coincided with testing of nuclear weapons in North Korea, and some heated rhetoric between the leadership of the United States and North Korea. Generally, the inquiries were around if these shelters were still viable, and if they would be effective in the event of a nuclear attack. The short answer to those questions is no, and maybe.

In the course of learning about this topic, I met Alex Wellerstein, a historian of science and nuclear weapons, and a professor at the Stevens Institute of Technology. Professor Wellerstein is a fantastic scholar in this field, and my conversations with him were nothing short of fascinating and enlightening. His commentary in this chapter shines a light on a lot of the nuances of the history and the present era in nuclear conflict.

Essentially, the global killing nuclear posturing of the United States and the Soviet Union has given way to more nuanced threats, with, in some cases, smaller nuclear warheads. The increasing number of states with nuclear weapons has also widened the possibility of regional conflict, and the proliferation of black market nuclear materials has increased concern over nuclear terrorism. A smaller nuclear blast is much more survivable with the right kind of preparedness, but it requires better understanding the current threat, and approaches to civic engagement that are elusive, and somewhat problematic with the legacies of the civil defense approaches in the United States.

What is particularly important about this chapter, is that if it weren’t for the urging of Dr. Redlener, I probably would have left it out. And now in having written it, I find it indispensable. As long as there are nuclear weapons in this world, there is the potential for their use. And ignoring the looming threat and the vulnerability that our complacency creates, the more likely it is to be one of the megadisasters we experience in our lifetime. I hope for those that stumble onto this book, they are encouraged not to forget that even with new potential disasters on the horizon, the old ones haven’t gone away.

We all have a stake in the future, and no matter what we do, our work contributes to what that future looks like. At a high level, that is a fairly agreeable sentence. But how does that translate into the multitude of transactions we engage in to build resilience? How do different sectors of society integrate resilience into how they make the decisions that, in aggregate, determine whether our threats and vulnerabilities grow or diminish? It is not sufficient to merely hand these challenges off to the disaster specialists and emergency managers to study and manage the consequences of our actions.

I often use the analogy of a Rubik’s cube to describe the impact of policy on disasters. You may be focused on one side, but you are changing many parts with each move. We need to look at our societal development the same way. We can’t focus solely on the piece that we own, but need to consider the broader impacts, and also the tremendous opportunities that come from doing so. We still need deep specialization in the sciences and within our bureaucracies. I am not arguing to break down the silos. Silos have purpose. But we need to bridge between them, share the insights we can draw from other fields, as well as the impacts that the decisions in one area have on others, so we can truly evaluate if the value of our development decisions are worth the risk.

For those already deeply immersed in the fields of disaster science and emergency management, I hope that the discussions in this book prove validating and energizing in recognizing how the field is evolving in the face of twenty-first-century disasters. And for those looking to enter the field, those in positions of influence, and concerned citizens, it is my hope that this book will garner additional understanding, and inspire deeper questioning and analysis into how we can all better prepare for the disasters that we can’t stop, and prevent the ones we can.

Finally, with all of the doom and gloom that is inevitable in talking about risks and our vulnerabilities, I remain hopeful. My optimism is not without criticism from others. But I truly believe that we have more knowledge available to us than ever before. And while distrust in science, and the growing polarization of our politics makes that hope seem futile, I have the privilege of seeing just how many brilliant minds and community organizations are stepping up to these challenges, and are not waiting for a cookie cutter answer or a tweet to tell them what to do.

The challenges we face from megadisasters in the twenty-first-century are not impossible problems, they are just really, really hard, and require new ways of thinking and collaborating to solve. I think we are up for this challenge, and in reading this book, I hope others do too.

Jeff Schlegelmilch is a Research Scholar and Director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Earth Institute. Prior to this, he was the Manager for the International and Non-Healthcare Business Sector for the Yale New Haven Health System Center for Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Response. He was also previously an epidemiologist and emergency planner for the Boston Public Health Commission. He holds a Master’s in Public Health from UMASS Amherst, and a Master’s in Business Administration from Quinnipiac University. He also holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Theatre Studies from The Theatre School at DePaul University.