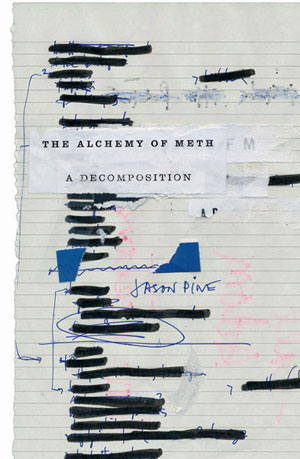

The Alchemy of Meth, to me, is really about the second part of the title, A Decomposition. It is steeped in the materials of meth making, but it is also an alibi for talking about decomposition in the United States in its multiple forms: the breakdown of everyday consumer products—the active unmaking of industrial chemicals in meth labs and their ordinary, passive leaching and off-gassing anywhere and everywhere; the slow deformation of any ordinary home and the accelerated transmutation of people and landscapes through biochemical tweaking and ecological injury; and the disintegration of the American Dream, which has had a very long toxic half-life.

The American Dream is the gateway drug. Intoxicated and triggered by it, some people reach for meth because it promises to make dreams come true. Meth increases energy and alertness. More importantly, it generates excitement about good rewards to come. This felt sense of futurity is like hope. The Alchemy of Meth is set in this overdrawn future. It follows how things, people, landscapes and lives have come to decompose and bust apart, leading the way toward how they are composed in the first place, and how they are recombining again and again in unforeseen ways.

I needed a form of writing that wouldn’t simply describe, or worse, explain decomposition, but instead perform it. At some point the answer became obvious: rather than compose a book (academic writing as usual), I made a decomposition. That is, the book is my refusal to overwork the material I gathered and subordinate it to authorial mastery (theory as usual). Of course, I am the author from beginning to end and every choice, even the most uncomfortable ones like self-exposure, is mine, but the decompositional form of the book—the fragmented and incomplete narratives and the third-person voice (free indirect discourse) that issues simultaneously from me and the author and the people I write about (including “Jason”)—leaves room, I hope, for readers to enter the text and make their own way.

So I hope readers do just that. I wield my authorial power not to direct their reading as much as to make one kind of reading untenable. That is, a comfortable, distanced reading that leers at a “them” in “that place over there.” Meth cooking is a hyperbolic version of something intimately familiar to a lot of people: coming undone while in pursuit of something greater, or simply something livable, in late liberalism. I implicate myself and I hope the book implicates readers. More than anything, I want readers to feel something for the people whose stories make the book what it is.

I’m an anthropologist but I’ve struggled with the discipline since I began studying it in the 1980s. That was a time when some anthropologists were focusing on the taken-for-granted medium of writing and its underexamined potential for symbolic and material violence. It was also a time when some rigorously experimented with genre. Authorial violence is always present, but can an author at least mitigate it? I’ve never stopped thinking about this question and one answer I’ve come up with is to fully own my authorial power and, rather than apologize for it, skillfully wield it.

One way I do this is by submerging theory in the matter of what I’m studying rather than elevate it so that it hovers above as the voice of explanation. So, while this book is influenced by literature on affect and new materialisms, it doesn’t serve these literatures as a ‘case.’ The theory is performed in the writing.

Affect theory taught me that if you want to follow what’s happening in a scene, then persons, agency, and autonomy are a bad place to start. Forces often precede and exceed little humans and humans anyway are always more-than-human—they operate in concert with the media, materials, and other beings that make them possible. Literature on new materialisms helps me think about the implications of this lost traditional liberal subject. It gives me ways to write about objects, which sometimes crowd out the little humans. It also gives me ways to think and write ecologically, which necessarily includes postnatural ecologies like the late industrial landscapes The Alchemy of Meth is about.

A second way I take up my authorial power is by using literary techniques to ignite a scene around protagonists and pull readers in to join them. I’ve been studying creative writing because I feel strongly that my ethical charge is to reach as many readers as possible well beyond the academy. I’m not writing for my elite cohort alone. I want the people whose voices are in the book to read it without feeling alienated and inadequate. They already have plenty of things in their lives making them feel like that.

When I began writing this book I knew I was looking for a form adequate to the matter. That became a decomposition. It was only very late in the writing that I accepted that I was motivated, in part, by very personal reasons: my mother’s meth use and my own use of legalized speed, ADHD medication. My chemical proximity to the people I was writing about implicated me and my writing. Rather than clean myself up and regain composure as an academic, I performed the sickly task of exposing my personal life, including my struggles with writing, in the writing. The decomposition that I found to be adequate to the matter I was writing about has no limits, so to arbitrarily halt the decomposition when it reached me would have been entirely unethical. And that’s a third way I address authorial violence: I turn it on my own authority.

If a potential reader were to simply browse the book, I hope they would quickly find a page from one of the meth cooks’ stories. They are sensitive, wounded people who have done things some people may not be able to accept. This tension would then stir up an upsetting feeling, and I would hope that the feeling stayed with the reader all the way, if they were to read the whole book. I originally wanted to publish the book without any introduction because I feel the stories speak for themselves. I wouldn’t want readers to get distracted by the introductory material, but because the book is very experimental in form it’s necessary to guide readers a little bit.

I spent lots of time with each of the cooks, except for Howard Lee, a person I never met and who I represent only through reproductions of the documents I found in his busted and abandoned trailer home. All of the cooks wanted me to help them or others who might end up like them, or worse. I want a reader to get pulled in like I was and to feel the burden of reading like I felt it while listening. I want them to find a page from the story of Christian, which I found difficult to hear because of its resonance with the story of my own family. I want them to feel how he never had a chance. I want them to notice how I crossed the line while writing about his mother, nearly reducing her to his abuser. Then I want them to find the letter Christian wrote to me from prison, in which he describes his mother’s quirky rock collection and her deep care for animals, and how he loved her dearly. I want the reader to feel that the integrity of the author and of the book is at risk, sometimes barely holding together. Sometimes stories and people and places are laced with sadness, rage, and delusional hope, and that’s what holds them together.

What can a book do? This is the question The Alchemy of Meth poses in the very beginning. Book-writing was the task I was left with after some very distressing fieldwork in Missouri. People on the brink of coming undone pinned their hopes on my work. Maybe a book can influence policy, but what policy would the book target when the problems that underlie the scenes depicted are systemic? Maybe a book can serve as a self-help text, but that’s not my expertise and, at any rate, there’s a lot more that I want to convey.

The question is more pressing in the academy, where uncountable books are published and sold to small elite audiences year after year. The way that many academics write and the poor marketing resources of academic presses limit what a book can do.

The Alchemy of Meth is undoubtedly an academic text. It is grounded in some of the ideas that animate scholarly and artistic work of late. At the same time, it uses these ideas to test the limits of the containers that circulate them—that is, theoretical arguments, books, and intellectuals with composure. It is a decomposition that deforms everything. But all of this is likely more apparent to those readers who are looking for the book’s argument or know some of the literature that helped me write it.

The book is largely literary nonfiction. It is a storybook where readers are invited to identify with the protagonists. They are invited to go far into scenes worked up into strange material constellations, scenes they might not otherwise ever know, yet sense as somehow familiar. Storytelling can deeply affect readers and I hope that readers are moved enough to care about the people whose stories are in the book. And if they care about the people, then they probably will also pay attention to the bigger story of the toxic inheritances of late industrialism in places like northeastern Missouri, where making a decent living can feel forever out of reach. Or the even bigger story of late liberalism throughout the United States, where you can never expect enough from yourself, and where fatigue, malaise, and doubt are regarded as life aberrations that obstruct nonstop individual ‘growth.’ This is a story that we all live, in some measure, and if more of us pay attention to it, more of us might feel like we can actually refuse to live it.

Another limitation on what a book can do is the general decline in readers. I was very happy when Blackstone Publishing bought the rights to turn The Alchemy of Meth into an audiobook and chose me as the narrator. An audiobook might entice some readers back as listeners. It’s like I’ve been given one more chance to share these stories. And if I manage to share them with my most favored readers (or listeners), maybe they’ll feel that they matter a little more.

Jason Pine is Professor of Anthropology and Media Studies at Purchase College, State University of New York. His research straddles the areas of political economy, political ecology, and medical anthropology. His first book, The Art of Making Do in Naples (Minnesota, 2012), is about a Neapolitan pop music scene operating in the margins of organized crime. His work has received the Premio Sila, the Berlin Prize, and support from the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the Science History Institute. Jason also works in other media: photography, video, installation, and performance lectures. In 2020 he narrated the audiobook version of The Alchemy of Meth, distributed by Audible.