Vice and addiction have always been with us. The Age of Addiction shows how entrepreneurs melded vices and addictions into a global economic system of limbic capitalism, outmaneuvering reformers determined to contain the damage through regulation and prohibition.

“Limbic” refers to the brain region responsible for pleasure, motivation, and long-term memory essential for survival and reproduction. Yet the same system can be captured by others and made to work against us. Limbic capitalism hurts us by systematically undermining appetite control.

The chief means of subversion are products that provide quick hits of brain reward, ranging from old standbys like drugs and alcohol to the latest social media and gaming apps. Technological innovation enables limbic capitalists to sharpen and multiply commercial hooks, catching more of us with products that encourage excessive consumption and addiction.

The “and” is important. Not all forms of excessive consumption are addictions. Yet regular, heavy consumption has a way of shading into addiction, as when a steady drinker’s craving intensifies and erupts into full-blown alcoholism.

The odds of addiction depend on both personal and social variables, which is why arguments about causation are heated. What I want readers to see is that the social causes are historically contingent. Limbic capitalism, a potent force today, was not always so. It emerged gradually from the ancient human quest to discover, refine, and blend novel pleasures. The likelihood that this quest would spawn addictions grew as entrepreneurs rationalized—that is, made more scientific and efficient—the trade in brain-rewarding products and pastimes. Commercial vice became more dangerous as it became more McDonaldized.

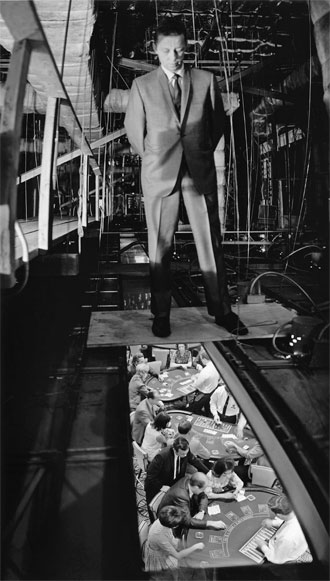

Limbic capitalism overlaps with surveillance capitalism. The photograph of one-way surveillance of the Mint Hotel in Las Vegas, taken in 1969, shows a pro gambler watching for card counters and cheaters among the tipsy tourists on the casino floor, sheep waiting to be sheared. But one can as well imagine Ray Kroc contemplating McDonald’s customers in 1979. Or Philip Morris executives studying Marlboro smokers in 1989. Or Anheuser Busch ad men quizzing Super Bowl focus groups in 1999. Or pornographers tracking site visitors in 2009. Or Juul marketers targeting teenage vapers in 2019.

The photo’s James Bond-ish quaintness (pressed suits! one-way mirrors!) reminds us of limbic capitalism’ recent, high-tech surge. Today digital cameras enable jeans-clad casino employees to monitor more territory, more quickly. Blackjack tables and dealers have given way to serpentine rows of blinking video poker and slot machines. House-issued debit cards track gamblers’ play. Algorithm-generated incentives keep them glued to their custom-designed chairs.

Digital technology did not invent limbic capitalism. It did supercharge it by firing all five cylinders of the engine of mass addiction: accessibility, affordability, advertising, anonymity, and anomie.

I wrote the Age of Addition to explain why addiction has become so widespread, conspicuous, and varied. When I entered the field in the 1970s, as a doctoral student studying opiate history, “addiction” referred to drugs like heroin. By the 2010s it also referred to compulsive overeating, sugar consumption, machine gambling, social-media use, internet pornography, shopping, and habitual tanning.

Though behavioral addictions remain controversial, they are, at a minimum, social facts. When I told people that I was writing an updated history of addiction, they said without prompting that I had to include kids glued to their smartphones. What had once been a peripheral nuisance had become a real worry, given the dangers of distracted driving and reports of increased bullying, anxiety, and academic failure among heavy users.

I knew something about addictive products. In 2001 I published Forces of Habit, a global history of psychoactive drug use, commerce, and regulation that went beyond my early work on opiates. Over the next seventeen years I became convinced, thanks to anthropologists like Natasha Schüll and journalists like Michael Moss, that drugs were not the only things with drug-like effects. Mesmerizing video slots and foods loaded with sugar, salt, and fat could also do the trick. Psychologists like Bart Hoebel and neuroscientists like Nora Volkow made similar arguments. So did behavioral economists like George Akerlof and Robert Shiller, who showed how corporations used habituating, brain-rewarding products to “phish for phools.”

When I joined the addiction-research peloton I found myself pedaling alongside other historians. One was the late John Burnham, author of Bad Habits: Drinking, Smoking, Taking Drugs, Gambling, Sexual Misbehavior, and Swearing in American History (1993). Burnham’s brief was that the vices of the Victorian male underworld had gone mainstream. Repeal of Prohibition, World War II, consumerism, the upheavals of the long 1960s, and countercultural and libertarian activists had undermined the crumbling façade of traditional morality.

Burnham’s book appeared in 1993, before processed foods and digital technologies featured in discussions of addiction. Seeing a chance to update and globalize his pioneering study, I cast The Age of Addiction as a sequel to Burnham’s Bad Habits as well as to my own Forces of Habit.

Injecting neuroscience into world history and arguing that an emerging economic system cuts across cultural differences raised some academic eyebrows. Against this, foreign journalists immediately grasp limbic capitalism when they interview me. “Hey, that’s us too.” Limbic Capitalism almost became the book’s main title, some editors preferring its edginess. Familiarity with brain regions being less universal than awareness of addictions, the current title won out.

Not everyone is happy with all the talk of expanding addiction. It bothers clinicians who fear stigmatization, libertarians who smell an excuse for indiscipline, social scientists who fear neuroscientific reductionism and imperialism, and philosophers who detect concept creep and equivocation, the misleading practice of using the same word to describe different things.

I shared many of these concerns and wanted to give the critics a hearing. Using the brain-disease model of food addiction as a case study, I wrote a dialogue that boiled down the arguments on both sides. Here’s a taste of the pros (P) and cons (C):

C: You can’t compare drugs and food. We don’t have to take drugs. We do have to eat.

P: Eat food, yes. Eat engineered food, no. People don’t overconsume corn. They overconsume corn processed into Cheetos, Doritos, and other mass-marketed, synthetically flavored products designed to maximized brain reward.

C: So take junk food off the grocery list.

P: Not so easy if you’re hooked.

C: Get unhooked. This is a bad habit, not a real brain disease like schizophrenia or multiple sclerosis. People quit bad habits all the time.

P: People don’t quit cravings or forget cues. They don’t restore lost receptors with a snap of the fingers.

C: But they can overcome bad habits by adopting other, healthier habits. They can change their routines. Start going to Weight Watchers, stop going to McDonald’s. What you call addiction has an element of choice and a developmental trajectory. People wise up as they get older. They outgrow addictions, often quitting on their own. Ex-tobacco smokers outnumber current smokers in several developed nations.

P: Yet people have to eat, as you say. And shop for groceries. Talk about cues. But, yes, there are workarounds like learning to prepare meals with fresh, carefully measured, low-fat ingredients. And avoiding fructose, which is nothing but a brain-pleasing additive.

C: The vast majority of people eat and drink fructose at least occasionally. Ditto other feel-good additives. Yet they don’t all become addicts.

P: You could say the same thing of drugs. Fewer than 20 percent of the people who ever try crack or heroin wind up as addicts. More people than that have trouble controlling their food intake, ruining their health in the process …

You can guess what follows. Is food addiction about dumb policies that make brain-altering and potentially addictive processed foods available at low cost to susceptible populations with few healthy alternatives? Or is it about dumb people who lack the discipline and future orientation to establish healthy regimes to maintain proper weight and nutrition?

Tell me what you think about food addiction—any addiction—and I’ll tell you what your politics are.

Drafts of The Age of Addiction provoked two different sorts of criticisms. Either I had been too quick to accept the idea of novel addictions, or I had underrated the hydra-headed menace of limbic capitalism and failed to show how to counter it. The book, historian Bill McAllister told me, was really about who controls our brains. Naming the system was not enough.

The second charge troubled me more than the first. Behavioral addictions are obviously subject to hype, and not every form of consumer excess is an addiction. In fact, one way to describe proliferating addictions is simply as the most harmful endpoints on different spectrums of excessive consumption.

Yet the harms are real, often lethal, and bear the stamp of corporate design and business rationalization. What could be done about the McDonaldization of old and new vices?

A lot, it turns out. We have options like education, taxation, age restrictions, prescription-only sales, advertising bans, spatial segregation (smokers freezing outdoors), digitally decluttered environments (favored by wary elites), lawsuits, international treaties to control supply and marketing, manufacturing quotas, and state monopolies designed to limit supply and intoxication. Blanket prohibitions have not worked well, as organized crime typically steps in when licit commerce is outlawed. But combinations of the other policies have produced some public health victories, such as the recent leveling off and decline of global per capita cigarette consumption. Limbic capitalists don’t win them all.

Limbic capitalists are likewise vulnerable to ridicule. BUGA UP, Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions, was founded by Australian anti-smoking activists in 1978. The acronym punned on Aussie slang for screwing something up. What the activists screwed up was billboards, which they altered with spray paint. Overnight “Have a Winfield”—a popular Australian cigarette brand—became “Have a Wank.”

Cheeky populism worked. In 1992 the Australian government outlawed all tobacco ads save for those at point of sale. It was a victory for activists like Arthur Chesterfield-Evans, a spray-can-wielding surgeon who gave a defiant speech to a crowd gathered around a Sydney billboard. “After six years of surgery,” he said, “I could accept that people suffer and die. But I had real trouble coming to terms with the fact that cigarette diseases were the result of a cold-blooded and systematic campaign of deception waged by monied interests against less informed consumers.”

Then the doctor climbed a ladder, rattled his can, and spray-painted “Legal drug pushers the real criminals.” The cheering, placard-waving crowd joined in, covering the ad from top to bottom with mocking graffiti. The police, who were looking on, did nothing to stop them.

All of this happened back in 1983. More than a generation later we still live in a world in which monied interests wage cold-blooded and systematic campaigns of deception against less informed consumers, above all those with low levels of education and social status.

The question I leave for readers is this: Do we, like Dr. Chesterfield-Evans, have the moral courage and political wit to do something about it?

David Courtwright is Presidential Professor Emeritus at the University of North Florida. He is best known for his books on drug use and drug policy: Dark Paradise (1982, 2001); Addicts Who Survived (1989, 2012); and Forces of Habit (2001). The Age of Addiction: How Bad Habits Became Big Business, was published by Harvard’s Belknap Press in May 2019. He is also the author of No Right Turn: Conservative Politics in a Liberal America (2010), featured in his previous Rorotoko interview. He lives with his wife, Shelby Miller, in the sunny climes of Jacksonville, Florida, in the sort of neighborhood where baby boomers have to be dynamited from their houses.