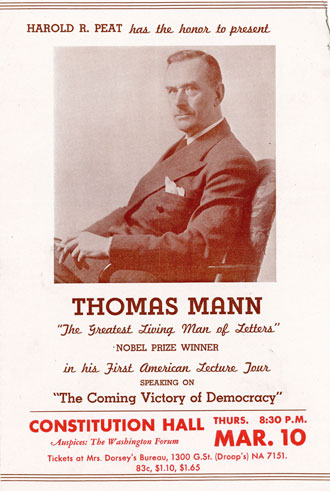

My book tells the story of the German novelist Thomas Mann’s anti-fascist activities during the period of his American exile, which began in 1938. Mann had won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929 and was one of the world’s most famous literary celebrities when he settled in the U.S. nine year later. At a time when many Americans still clung to the isolationist ideas that had governed U.S. foreign policy for the previous decades, Mann was adamant about the need to defend the ideals of liberal democracy against the threat posed by the Nazis. He wrote essays and op-eds, visited the White House, and embarked on lecture tours that reached hundreds of thousands of people.

On one level, then, this is a work about a forgotten chapter in the history of World War II. It’s also a book about the nature of literary celebrity, however. I’m very interested in how Mann came to be so famous in the United States. After all, the circumstances greeting him there were far from auspicious. During World War I, there had been a massive backlash against all things German, up to and including book burnings. And Mann was a difficult writer who barely spoke English when he first arrived in America. How did he become an anti-Nazi icon, an author who was not only followed by intellectuals, but publicly cheered by ordinary people?

To answer this question, I’ve documented in meticulous detail how Mann was advertised and promoted during the 1920s and 1930s. Doing so also forced me to engage with more fundamental questions, namely: what were Americans reading and what drove their choices? What, other than simple entertainment, did they hope to get out of books? As it turns out, the answers to these questions changed over time, and Mann’s American allies—foremost his publisher Alfred A. Knopf and his patron Agnes E. Meyer—were incredibly skilled in changing their marketing tactics to accommodate shifting demands.

Mann’s story forever changed the public role of the author in modern society. Americans came to believe that he represented the true voice of a great cultural tradition that Nazism had perverted. And this belief that literature can give us insight into foreign cultures that are struggling with war and authoritarian oppression is very much with us even today. It explains the success of The Kite Runner, for example, Khaled Hosseini’s novel about Afghanistan that was published in the wake of the 2001 U.S. invasion.

Ultimately, then, this is more than a work of literary history. I hope it will lead readers to reflect on the ways in which they use books in their everyday lives.

Although Thomas Mann’s War is primarily a book about the 1930s and 1940s, I embarked on the project because of my interest in contemporary literature. This connection came full circle about halfway through the writing process, with the Brexit referendum, the rise of right-wing populism throughout Europe, and the election of Donald Trump. Suddenly, a lot of the historical phenomena were tremendously relevant again!

Back in 2013, when I first conceptualized my book, I attended a talk by the Rutgers English professor Rebecca Walkowitz, in which she presented research that would eventually form the core of her 2017 study Born Translated. Walkowitz argues that successful contemporary novelists write their fiction with full knowledge of the fact that it will be consumed globally, rapidly translated, and published in many different country-specific editions. In anticipation of this, these writers consciously alter their style to suit global markets.

A lot of what Walkowitz was saying seemed to me immediately applicable to Thomas Mann, about whom I had already written in my first book, Formative Fictions. Separated from his German readership by the censorship of the Nazis, Mann was a master manipulator of his global reputation, who knew that his work would primarily be received in translation. And he had skillful allies in the form of his publisher, his translator, and so on. His case thus seemed to provide a perfect opportunity to study how the contemporary global publishing industry was born from the pangs of World War II. This was, after all, a global conflict in which culture and media were deployed in hitherto unimagined ways.

At the same time, the example of Thomas Mann seemed to complicate some of Walkowitz’s theories in ways that also allowed me to engage a second scholarly influence of mine, the French literary sociologist Pascale Casanova. In her influential study The World Republic of Letters, Casanova argues that writers who want to rise to the highest levels of global literary esteem inevitably need to avoid becoming overly associated with any national literary tradition. But this was manifestly false in the case of Thomas Mann, who ascended to celebrity status in the 1930s largely because of his carefully cultivated reputation as a representative of German culture. And it wasn’t hard to find contemporary writers who imitated this pattern. The Turkish Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk, for example, or the aforementioned Khaled Hosseini.

Then Brexit and all those other events happened. Suddenly, the question whether global or national forms of cultural validation are more “authentic” was the stuff of front-page opinion pieces. At the same time, fascism, which Mann had so valiantly opposed in the name of liberal democracy, made a comeback. I wish some of the things Mann said back in the 1930s (for instance, about the great difficulty of giving democracy an emotional rather than merely intellectual relevance) weren’t so topical nowadays, but there you have it.

Most readers browsing through the book in a bookstore will probably end up lingering over the fourth chapter, which has not only a catchy title (“Hitler’s Most Intimate Enemy”), but also a large number of arresting visuals. Among these is my favorite picture in the book. It shows a pro-Nazi color guard of the German American Bund assembled in front of a giant portrait of George Washington in Madison Square Garden. Nowadays, we are so used to triumphalist narratives about the “greatest generation” that we forget how, prior to Pearl Harbor, there were powerful anti-interventionist and even pro-Nazi forces in America.

The chapter analyzes Mann’s activities on the American home front during the early years of World War II: his lecture tours, his addresses to Washington insiders at the Library of Congress, his anti-Nazi essays, and his participation in various conferences and committees. Mann tirelessly urged ordinary Americans to defend liberal democracy against authoritarian encroachment, and he clearly struck a nerve. Journalists report that New Yorkers would cheer when they saw his face on a newsreel at the local movie theater.

Honestly, though, the chapter that I’m most proud of is probably the fifth, which deals with the fate of Mann’s books on the European continent during the years in which the Nazis were assembling their empire. I’m very interested in what my colleague Venkat Mani has called “bibliomigrancy”—that is, the question how the physical journey of books contributes to their reception and to their place in the literary canon.

When we think about books and the Nazis, the first thing that comes to mind are the bonfires upon which they burned the works of authors they deemed undesirable. But it’s not as if all of Mann’s books simply went up into smoke during the years from 1933 to 1945. In fact, Mann’s German publisher Gottfried Bermann Fischer played a game of cat and mouse with the Nazis. He moved his operations first to Austria, then to neutral Sweden, and finally, in part, to the United States. From there, he oversaw ever-changing distribution chains that put Mann’s newest works into the hands of readers not only in neutral countries, but also in fascist states such as Romania. The movement of books became directly tied to the movement of armies. For instance, Sweden was allowed to export literature across Nazi soil in sealed freight cars because in return it allowed the Germans to transport military materiel into occupied Norway.

As a result of these journeys, the books themselves were changed, and so was the image they conveyed of their author. One of my most cherished possessions is a copy of the so-called “Stockholm Edition” of The Magic Mountain, which my grandfather purchased after the war. It begins with an explanatory preface that Mann had composed at Princeton, and in which he praises the acuity of a Jewish-American critic. What might his European readers have thought of this essay as they hunkered down to read Mann’s work amidst the wailing of air-raid sirens?

The reception of Thomas Mann’s War has been irrevocably altered by the events of 2016. The first major review of my book, for example, was published in The National Interest, a policy journal that steers a conservative but anti-Trump line. The reviewer, Jacob Heilbrunn, was thoughtful and well informed. Nevertheless, it was clear he was drawn to my book not because of Mann’s literary importance, but because he saw in the author the very model of an impassioned conservative response to authoritarianism and anti-intellectualism. Most audiences to whom I have presented my project react in the same way.

I feel somewhat ambiguous about this reception, and not just because I have my doubts about Thomas Mann’s often-postulated political “conservatism.” The question also has to be asked what his example can actually teach us in the present. We live in a radically different social moment, and amidst a radically different media environment than did Mann. Somehow, I don’t think that a cultural commentator with his undeniably patrician demeanor will be able to reverse the damage done to our democracy on Twitter through thoughtful opinion pieces in The New Republic or The Atlantic.

Still, the fact remains that Mann provides a powerful illustration of the fact that it is possible to accept globalization without losing one’s roots in a specific cultural tradition, and to reject nationalism while simultaneously embracing patriotism. And Mann understood that democracy—to summarize his words—“will die off, disappear, be lost, if it is not cared for.” That is certainly a lesson that too many of us across Europe and North America have learned far too late.

Beyond these political implications, I also hope that Mann’s story will help illuminate the contemporary literary landscape. For example, I had to think about Mann a lot during the turmoil that followed the announcement of Peter Handke’s 2019 Nobel Prize in Literature. Handke, of course, is infamous for denying that the Srebrenica massacre took place. His defenders in the German-speaking press argue that these political missteps should not matter, and that the Nobel Prize is awarded solely for aesthetic merits. This is a line of reasoning familiar to any Mann scholar. When Mann won his Nobel Prize in 1929, the influential member of the Swedish Academy Fredrik Böök similarly let it be known that The Magic Mountain, Mann’s dissection of the venomous ideologies that had led to World War I, had played no role in the committee’s deliberation. Instead, the prize was awarded in recognition of the thoroughly unpolitical Buddenbrooks.

My detailed reconstructions of Mann’s changing celebrity during the 1930s shows how specious these arguments are. Mann’s esteem as a Nobel laureate was very quickly tied to his political actions. Handke’s defenders not only embarrass themselves by downplaying genocide denial, they also show themselves to be insufficiently informed about the literary tradition that they claim to serve.

Tobias Boes is Associate Professor of German at the University of Notre Dame, where he is also affiliated with the Nanovic Institute for European Studies. He is the author of Thomas Mann’s War: Literature, Politics, and the World Republic of Letters, which is featured in his Rorotoko Interview, and of Formative Fictions: Nationalism, Cosmopolitanism, and the Bildungsroman, which was published by Cornell University Press in 2013. His research focuses on the global reception of German culture, and on the interrelationship between literature and politics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.