The Embattled Vote explains why Americans have fought and died for the right to vote. The book is more relevant than ever after the Supreme Court sanctioned partisan gerrymandering in a ruling issued on June 27, 2019.

The world’s oldest continuously operating democracy guarantees the franchise to no one, not even citizens. This lack of universal voting rights originated in a crucial mistake by America’s founders: omitting a right to vote from the Constitution and leaving the franchise to the discretion of individual states. During Reconstruction, Congress missed an opportunity to rectify the founder’s error and enshrine a positive right to vote in the Constitution. Instead, they framed the Fifteenth Amendment on racial voting rights negatively, in terms of what states could not do. They set a precedent for later amendments on sex and age.

The lack of a constitutional guarantee has meant that the right to vote has both expanded and contracted over time. In the early republic, only those with a “stake in society” proven through the ownership of property or the payment of taxes could vote in most states. In the nineteenth century, states eliminated economic qualifications but embraced the ideal of a “white man’s republic,” with people of color and women excluded from the franchise.

Despite advances since adoption of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, our voting rights are still in jeopardy. Politicians that benefit from voter suppression rely on bogus claims of voter fraud to deprive millions of American of the franchise through voter identification laws, political and racial gerrymandering, registration requirements, felon disenfranchisement, and voter purges.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down one of the Act’s most effective provisions, which required states and localities with a history of voter discrimination to preclear changes in voting laws and procedures with the U.S. Justice Department or the Federal District Court in D.C. The Court held that the “pervasive,” “flagrant,” “widespread,” and “rampant” discrimination that Congress sought to correct in 1965 no longer existed in the 21st century.

Yet, by neglecting new forms of voter suppression, the Court unleashed a renewed push to erode voting rights. Dallas minister Peter Johnson, a civil rights activist since the 1960s, said, “There’s nobody that’s going to shoot at you if you register to vote today. They aren’t going to bomb your church. They aren’t going to get you fired from your job. You don’t have those kinds of overt, mean-spirited behaviors today that we experienced years ago … They pat you on the back, but there’s a knife in that pat.”

Historically, players in the struggle for the vote have changed over time, but the arguments remain depressing familiar and the stakes are very much the same: Who has the right to vote in America and who benefits from exclusion?

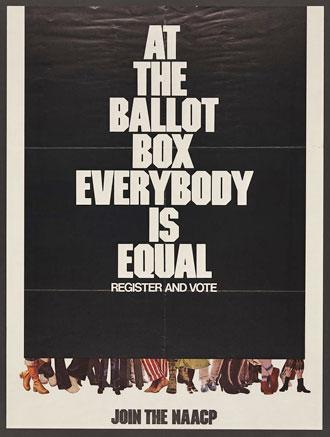

The Embattled Vote shows how the right to vote grounds participation in the decision-making of America’s democratic republic. Extreme disparities in income and wealth are embedded in today’s America. But all Americans are equal in the polling place. The future course of U. S. politics will depend on the level of voting participation by American citizens.

The real problem with democracy in America is not the nearly non-existent voter fraud that politicians use to justify restrictions on the vote, but low voter turnout. Nearly 40 percent of American citizens did not vote in the tightly contested presidential election of 2016, leaving some 90 million votes on the table. Turnout is far lower in primary contests that set the choices for voters in general elections. Only about 8 percent of American citizens chose Hillary Clinton as the Democratic nominee and only about 6 percent choose Donald Trump as the Republican nominee.

A shattering study by political science professors Martin Gilens of Princeton University and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University found that not ordinary Americans, but wealthy interests, seeking profit, power, and control, shape policy outcomes in the United States. The influence of ordinary Americans over policy registers at a “non-significant, near-zero level.”

Until the late twentieth century, Democrats in the South mainly benefitted from restrictions on the franchise. Now it is Republicans that benefit. The GOP’s base of older white Christian voters is the most shrinking part of the electorate. The party cannot manufacture more of these voters, but it can attempt to limit the rising Democratic base of racial minorities and young people. America is moving toward two separate democracies, a more restrictive one for red states and a more expansive one for blue states.

My interest in voting rights is both academic and practical. As a graduate student at Harvard University in 1967 I wrote a research paper on enforcement of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first voting rights law since Reconstruction. This work alerted me to the many obstacles that still confronted potential voters in America and led to my work as an expert witness in voting rights litigation.

To date, I have worked as an expert witness in more than 90 voting rights cases. Nearly every case was fiercely contested, with white leaders battling to keep the privileges that flowed from control over politics in their states and communities. This experience infuses the pages of The Embattled Vote. It brings life and excitement to my account of the unending struggle for voting rights and provides an insider’s account of landmark cases available from no other source.

I would turn your attention to pages x and xi of The Embattled Vote, which illuminate my work as an expert witness in voting rights litigation. In the 1980s I worked mainly on cases challenging the outright exclusion of minorities from participation in governance. Recently, however, my work has evolved to litigation dealing with racial and partisan gerrymandering, photo ID laws, and other thinly disguised restrictions on the franchise.

My greatest satisfaction still comes from my early work in localities like Selma, Alabama – the birthplace of the Voting Rights Act — where whites had oppressed black people throughout their lives. At the risk of their livelihoods and safety, African Americans often joined civil rights groups as plaintiffs in voting rights law suits.

Consider also pages 53 and 54 that describe America’s first voting rights lawsuit, filed not in the 1960s, but in the 1830s by William Fogg, a black citizen of Pennsylvania. Fogg and other excluded voters had no recourse to the federal courts because of the Constitution’s silence on voting rights. He charged in state court that election officials had violated Pennsylvania’s color-blind constitution by barring him from voting because he looked black. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court rejected Fogg’s claim by writing black people out of American democracy. It found that “no coloured race was party to our social compact,” and that Pennsylvania should not “raise this depressed race to the level of the white one.”

Examine pages 256-257 where the book draws attention to the current crisis of American democracy. It cites ideological polarization, cynicism about government, lagging voter turnout, and unchecked foreign interference in American elections. In some ways, today’s democracy resembles the economic stakeholder model of the eighteenth century. Restrictions on registration and voting and alienation from politics have produced a cadre of nonvoters that is disproportionately minority, young, and economically disadvantaged.

Then turn to Chapter 8 on “Reforming American Voting.” It introduces and explains the reforms that can redeem our democracy. I discuss these innovations below.

I wrote The Embattled Vote as both a history and a call to action. A New York Times review said that it “uses history to contextualize the fix we’re in today. Growing outrage, [Lichtman] thinks, could ignite demands for change. With luck, this fine history might just help to fan the flame.”

Outrage over the Supreme Court’s abdication of a judicial check on partisan gerrymandering should rivet attention on the remedies in Chapter 8. The state of Florida ironically offers an anti-gerrymandering model for the nation. In 2010, 62 percent of Florida voters backed a state constitutional amendment to restrict partisan gerrymandering for congress and the state legislature. After years of resistance from Republicans in the state legislature, the state courts compelled the redrawing of district lines to treat each party fairly. Florida-style amendments could be effectively combined with redistricting conducted by independent commissions to stifle pernicious gerrymandering, with enforcement by the state not the federal courts.

An affirmative right to vote amendment, like the version of the Fifteenth Amendment that Congress rejected in 1869, would bring America into line with most other democratic nations and with international conventions. It would not invalidate every restriction on the vote, any more than the right of free speech invalidates libel and slander laws. But it would rebalance the scale of justice in favor of the voter, not the state.

Other reforms are in reach even without a new amendment. A lack of registration locks out tens of millions of potential voters. The opportunity to register when showing up to vote and automatic enrollment when applying for or renewing a driver’s license or applying for government services, could substantially reduce this barrier. Other reforms with the potential to expand turnout and improve the conduct of elections include a restoration of Justice Department preclearance, elimination of felon disenfranchisement, and federal aid for upgrading voting technology and protecting the vote from manipulation by the Russians or another malevolent foreign power.

The Embattled Vote optimistically concludes that America can reclaim her place in the front ranks of the world’s democracies. Simple, practical reforms are within reach to enhance access to the vote in America, end discriminatory practices, and help assure that people’s vote will count effectively in the election of public officials. But change will come only if the American people demand it. America needs the kind of concerted grassroots action that led to enactment of the Voting Rights Act.

Allan J. Lichtman is Distinguished Professor of History at American University and the author of ten books. FDR and the Jews (with Richard Breitman), won the National Jewish Book Award in American Jewish History. Other books include The Keys to the White House and The Case for Impeachment and White Protestant Nation, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in non-fiction. He served as an expert witness in some 90 voting rights cases and as an expert for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights that uncovered the racial disparity in ballot rejection rates in Florida that gave George W. Bush the presidency in 2000.