From the voyages of discovery to the digital age, maps have been essential to five hundred years of American history. Whether made as weapons of war or instruments of reform, as guides to settlement or tools of political strategy, maps invest information with meaning by translating it into visual form. Maps captured what people knew, but also what they thought they knew, what they hoped for, and what they feared. As a result, maps remain rich yet largely untapped sources of history. This premise animates A History of America in 100 Maps.

Organized into nine chronological chapters, the book examines both large-scale shifts but also little-known stories through maps that range from the iconic to the unfamiliar. Readers will encounter maps of political conflict and exploration, but also those whom we rarely consider mapmakers, such as soldiers on the front, Native American tribal leaders, and the first generation of young girls to be formally educated.

The book can be read as a continuous narrative, though readers may page through the book to discover a particular image that captures their imagination. Some will be drawn to the map used by the British Crown to negotiate the boundaries of the new United States at the end of the Revolutionary War. Others will be riveted by a map drawn to study—and stem—the rampant gang behavior in Chicago during the 1920s. Each map is accompanied by a brief essay that lays out its context, establishes its significance, and connects it to the larger story. Through these maps, we gain a greater appreciation for the contingencies of the past, but also the degree to which maps were integrated into all aspects of American life.

The book is now in its third printing. What has most surprised me about this success is the wide and diverse audience it has reached—a direct function of the many strange and appealing images that I was able to share.

I have a longstanding interest in old maps. My last book, Mapping the Nation, traced a sea change in the way that Americans and Europeans thought about and used maps across the nineteenth century. In 1800, most maps were either representations of the physical terrain or tools of navigation. By 1900 the explosion of “thematic” maps revealed that maps had come to be used not just to navigate the land, but as tools of analysis, communication, and visual representation.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, maps appeared across all areas of American life. Medical men turned to maps in an urgent quest to solve the deadly mysteries of yellow fever and cholera. Anti-slavery activists creatively used maps to persuade an ever-growing public to oppose the expansion of this institution into the western territories. And after the Civil War, the federal government actively began to translate census data into cartographic form in an effort to administer an increasingly diverse population. To illustrate the power of this shift in the meaning of maps, I developed a website. Today we live in a world saturated with maps and graphic information: Mapping the Nation explains how we got to this point.

While researching Mapping the Nation, I came to appreciate the extraordinary power that maps have not just to reflect but also shape historical change. Thereafter, I began to visualize a history of North America that was not just illustrated by maps, but explored through maps. Such a book hinges on the details of presentation, so that the educated general reader as well as the professional historian can appreciate the way maps mattered in history. The result is a book using maps to explore everything from the forces that governed settlement across North America to the battles across the western front in the Second World War.

In A History of America in 100 Maps, I avoid theoretical frameworks in order to foreground the meaning and use of the maps themselves. Such an approach reminds us that history was lived not just chronologically, but spatially. I also prioritized maps that challenged assumptions and familiar narratives, hoping to reframe the past in a way that would highlight the uniqueness of these graphic materials. For instance, an early eighteenth-century deerskin map forces us to recognize the fragility of the South Carolina colony relative to the native tribes of the Southeast in the 1710s. Several pages later, readers will find an 1832 map designed to teach geography to the blind, an image which captures crucial efforts to widen education in the antebellum era.

The opening image of the book may take some readers by surprise: it does not include America at all because it was drawn before Europeans “discovered” the western hemisphere. After the voyages of exploration in the 1490s, contemporary understandings of geography—and the world map—would forever be changed. Equally captivating is the final image of the book, a geo-visualization of data created for self-driving cars. Such a “map” is unlike any other in the book, for the data that guides autonomous vehicles is digital, never realized in a static form but always shifting. Yet as a tool of reconnaissance, movement, and discovery, it reminds us again that maps—above all else—shape decision making. To recognize this is to appreciate the power maps have to not just reflect the past, but to mediate it.

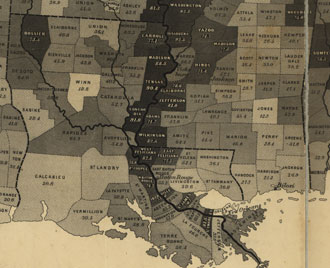

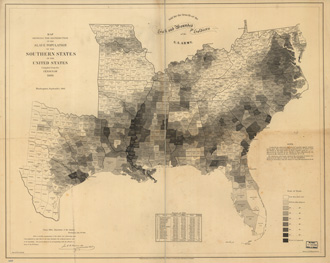

That power of maps to drive historical change is nicely revealed by one of the first maps of the U.S. Census, drawn in 1860 to profile the distribution of slavery on the eve of the American Civil War.

The map became a favorite not just of those on the Union home front, but also President Abraham Lincoln, who used it to construct a strategy to defeat the Confederacy. Though he initially promised to protect slavery where it existed, by 1862 Lincoln recognized that the rebellion would only be crushed when slavery itself—the Confederacy’s greatest resource—was destroyed. Emancipation was pressed first by slaves, then by Union generals, ultimately becoming a war strategy that culminated in the Thirteenth Amendment. The map riveted Lincoln because it showed him that the strength of the Confederacy varied by geography, a reality that lay hidden on other maps.

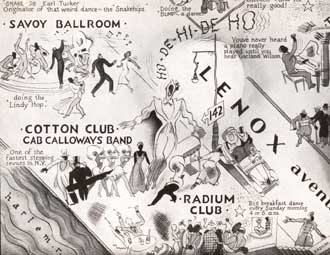

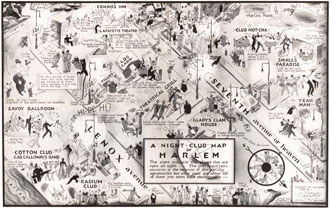

One of the most provocative maps in the book comes a few chapters later, in 1932: a bird’s-eye view of the creative chaos in Jazz Age Harlem, drawn by the noted African-American artist Elmer Simms Campbell.

Campbell arrived in New York after earning a degree in illustration at the Chicago Art Institute. While discrimination initially prevented him from working as an artist, he found solace in Harlem at the height of Prohibition. Guided by his best friend, Cab Calloway, Campbell immersed himself in the area’s energetic nightlife and profiled its most memorable characters. I use the map to explore not just that moment in time and place, but also the forces of migration, segregation, and culture that created Harlem and made it the capital of black culture in the early twentieth century. The map contains layers of commentary on race relations, gender dynamics, the selective enforcement of Prohibition, and of course contemporary jazz.

My hope is that this book demonstrates that maps are essential artifacts of history. Judging from the enthusiastic reception the book has had to this point, I have every expectation that maps and graphic materials of all sorts will only become more central to the study of history. In my own research, maps have put into high relief people and places that otherwise remain invisible to the historical record. For instance, by studying hundreds of manuscript maps drawn by schoolgirls after the Revolution, I’ve come away with a deeper understanding of the way women were educated. There are many more examples like this, where maps don’t just complement our beliefs about the past but raise new questions about it.

To put it briefly, when people hear me speak, or reach out to me about the book, the most common thing they say is this: I will never look at a map the same way again.

Susan Schulten is Professor of History at the University of Denver, where she has taught since 1996. Her previous books include The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880-1950 (Chicago, 2001) and Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago, 2012). She is also co-editor, with Elliott Gorn, of Constructing the American Past: A Sourcebook of a People’s History. Readers can explore A History of America in 100 Maps at www.america100maps.com.