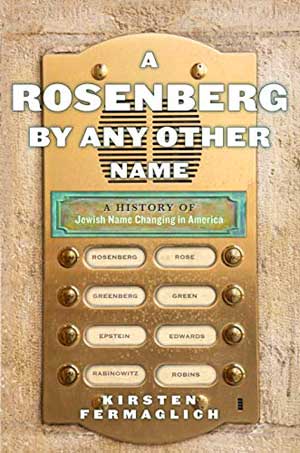

Despite the prevalence of name changing in American Jewish culture, few historians have studied the actual practice of name changing in the United States. A Rosenberg by Any Other Name – the first book to explore the phenomenon – relies on research into thousands of previously unexplored name change petitions submitted to the New York City Civil Court throughout the twentieth century. Using these petitions, I argue that name changing was a distinctive American Jewish practice in the middle of the century. Although many New Yorkers of different backgrounds changed their names, Jews did so at rates that were far disproportionate to their numbers in the city. They also changed their names together with family members in ways that historians have not considered before.

Jews’ middle-class status helps to explain these high rates of family name changing, as does the rising antisemitism of the era. Jews reached the middle class in the United States earlier than other immigrant groups in the early twentieth century, and they sought to maintain that status through education and white-collar work. By the 1920s, however, universities and employers were developing application forms, specifically, to weed out Jewish candidates by asking questions about birthplace, religion, and, importantly, name-changing. This institutionalized antisemitism formed the context for Jewish name changing in the first half of the twentieth century. Petitioners sought to erase the names that marked them as Jewish and thus exposed their families to discrimination.

The growth of the state during World War II further shaped the context within which Jews changed their names. As the government penetrated individuals’ daily lives to a greater extent, more Jews found it necessary to change their names officially to avoid discrimination and participate in the war effort.

During the war, Jewish communal groups understood name changing as a response to antisemitism, but after the war, the Jewish community became sharply divided over the phenomenon. Some Jewish leaders accused name changers of being “self-hating Jews” who were abandoning the community. A closer look at name change petitions, as well as contemporary literature, however, suggests that the majority of name changers remained members of the Jewish community, using their new names only to make it easier to work in the non-Jewish world. Jewish civil rights organizations understood this complicated balance, and defended name changers’ right to change their names as part of civil rights legislation in the 1940s.

Jews stopped changing their names in large numbers by the 1970s, and just as they did, negative representations of name changing flourished in popular culture. Misleading images of Jewish men betraying their families by changing their names or Ellis Island officials changing immigrant names circulated widely in the last quarter of the twentieth century. And since 2001, new ethnic groups have been changing their names in Civil Court for very different reasons than did Jews 75 years ago. Our culture has mostly forgotten the history of Jewish name changing in the United States. My book attempts to reconstruct that story.

The most important reality that my book interrogates is American antisemitism. American Jewish historians have traditionally downplayed the significance of antisemitism in the United States. They have tended to highlight Jews’ economic, social, and cultural successes, and treated antisemitism as a private, contained phenomenon that had little impact on Jews’ ultimate upward trajectory. The fact that American Jews did not face the same violence as African Americans or Native Americans or European Jews, and that Jews were, for the most part, accepted as white citizens throughout their history in the United States, has led American Jewish historians to minimize the existence of antisemitism in the US.

In the wake of the current resurgence of American antisemitism, however, many scholars, myself included, have begun to challenge this progressive narrative. (Indeed, many began challenging that narrative before 2016, as I did when I began my research in 2007!) For one thing, scholars have questioned the construction and the contingency of Jews’ whiteness. Recently, they have also begun to problematize the private/public division that has made American antisemitism appear so harmless. They have explored, for example, Jews’ efforts to respond to hate speech through legislation. They have probed Jewish responses to Nazi propaganda through cooperation with the state. In my own work, I look at the interrelationship between the state processes of name changing, and the mostly private systems of employment and educational discrimination. Now that white nationalists are shouting on the street “Jews will not replace us,” and even the tiniest of synagogues are installing security systems to prevent another Pittsburgh shooting, our contemporary society badly needs historians to do a closer accounting of the history of American antisemitism, to understand the context of today’s reality.

My professional path was not directed by these immediate political concerns, however. Instead, I came to the subject of name changing through my interest in secular Jews. My first book, American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares, looked at American Jewish social scientists like Stanley Milgram, who compared contemporary American politics with Nazi concentration camps in order to make liberal arguments.

I was particularly interested in these social scientists as Jews unaffiliated with the larger Jewish community. In what ways did their analogies reflect a Jewish identity, and in what ways did their views differ from the larger Jewish community? Much Jewish history is organizational history, and because it is, it frequently does not record the experiences of the large numbers of Jews who are not affiliated with a Jewish organization. Name change petitions gave me access to a broader sample of the American Jewish population—many of them might not affiliate with a synagogue but might still identify as Jewish. Name changing also gave me access to arguments within the Jewish community over boundaries: are name changers seeking to escape the community? Should the community cast name changers out of its midst? Does a “Jewish name” define you as a Jew? These issues of boundaries are crucial to understanding American Jewish life.

Page 55 contains some of the most interesting visual evidence that my book offers, with both methodological and historical significance. On this page, readers will find the “Distinctive Jewish Names,” or DJN list, a list developed by an American Jewish social scientist, Samuel Calmin Kohs, to count Jews for social welfare purposes. To create the list, Kohs asked a group of Jews and non-Jews to identify the names that they saw as exclusively Jewish; the agreed-upon 106 names on this list then became a part of Kohs’ counting methodology.

I find this list compelling for many reasons. For one thing, the names themselves—which include Goldberg, Epstein, Rosenberg—are just fascinating to look at. Individually, many of these names have been used as jokes or synecdoches for Jewishness. Brought together on one list, they offer a fascinating portrait of what it means to be a Jew: how Jews are perceived and understood through the linguistic signals of their names. One of the key points I hope to make in my book is that Jewish names do not have inherent Jewish meaning, but they were historically turned into racial markers of Jewish identity, markers that identified Jews and enabled their exclusion.

In addition to illuminating how Jewish names have determined and marked Jewish identity, the DJN list is a fascinating historical document of its moment, the early 1940s. Although Kohs initially constructed the list to help provide social services for Jews, he first used the list to help the National Jewish Welfare Board count the Jews fighting in World War II, in order to defend Jews against the claim that they evaded service. The list is thus a testament to the antisemitism of the era, while it also clearly notes how crucial Jewish names were for Jewish identity at this time.

Finally, the DJN list offers valuable methodological possibilities. If name change petitioners possessed one of these names, I counted them as Jews. (If they possessed other Jewish-sounding names, I used a host of other clues to determine if they were Jewish). As noted before, American Jewish historians have had difficulty studying secular Jews unaffiliated with the Jewish community. The distinctive Jewish names list—used judiciously, with appropriate qualifiers—can help historians to go beyond organizational records to consider secular Jews in America.

Certainly, using the DJN list throws a harsh light on the antisemitism that my research uncovered: using Kohs’ methodology, only about 3.75 percent of the New York population should have had a distinctive Jewish name found on the list. Yet roughly 30 percent of petitioners for a name change in New York City Civil Court had one of these 106 “distinctive Jewish names.” This disproportionality points to the stigma that Jewish names possessed during the 1940s, while it also offers insight into Jewish responses to that stigma.

I hope that this book will encourage more American Jewish historians (and indeed more Americans) to consider the significance and the meaning of antisemitism in American life, particularly in thinking about the relationship between the state and private actors. We need context to understand the politics of our contemporary era.

I also hope that the book will encourage more historians to take names seriously in general. Too often we use names as mere markers, rather than historical subjects themselves. But names are historical documents, full of historical meaning, and have not been explored enough.

Finally, I hope that the book will encourage all readers to reconsider the name changing in their own lives, or in their families’ lives. Name changing has too frequently been understood either as a joke or as a shameful abandonment of community. I would like my book to help readers consider the real struggles faced by Jews in the middle of the twentieth century, and the ways that those struggles shaped Jewish life and community.

Kirsten Fermaglich received her PhD from New York University in 2001. She has taught history and Jewish Studies at Michigan State University since 2001. In addition to her books, A Rosenberg By Any Other Name (2018), American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares (2006), and The Norton Critical Edition of the Feminine Mystique (2013), she has published in the Journal of American History, the Journal of American Ethnic History, and American Jewish History, among other venues. She has received grants and fellowships from the Frankel Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan, YIVO, and the Association for Jewish Studies.