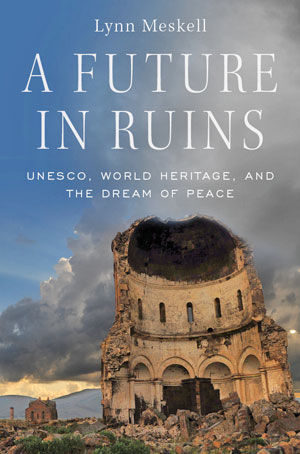

A Future in Ruins tells the story of UNESCO and its efforts to save the cultural wonders of the world, largely through its famous World Heritage program. I wanted to understand how and why the past comes to matter in the present, who shapes the political agendas, and who wins or loses as a consequence. Today it remains critical that we educate ourselves about the politics at work in cultural productions such as World Heritage and understand that we can never escape the past and are, in fact, too often doomed to repeat it.

Forged in the twilight of empire and led by the victors of the war and major colonizing powers, UNESCO’s founders sought to expand their influence through the last gasps of the civilizing mission. Beginning as a program of reconstruction for a war-ravaged Europe, UNESCO soon set its sights on the developing world. Its aim was to formulate and disseminate global standards for education, science, and cultural activities. However, it would remain a one-way flow, later to prove problematic, from the West to the rest. Within a matter of years, the philosophical appeal for cultural understanding and uplift, a culture of peace no less, would be sidelined by the functionalist objectives of short-term technical assistance.

Ruins were also on the agenda for reconstruction. But it was not simply that great buildings, museums, and art were affected by the war and required rehabilitation. It was the regulation of the past itself, and how it might be recovered, that was deemed part of a new world order. How archaeological excavations were conducted around the world and the resulting discoveries were disseminated also required restructuring. Ultimately, archaeology’s spoils were to be divided up for Western advantage, echoing earlier recommendations made by the League of Nations. The past would be managed for the future. UNESCO capitalized upon an already existing momentum for a world-making project devoted to humanity’s heritage. What followed was an inevitable progression from the vast conservation and restoration efforts needed in the wake of destruction after two world wars toward a more lasting project of rehabilitation and recovery.

While it is true that UNESCO status bestows a level of international prestige upon ancient sites, for archaeology as a discipline the organization means very little. World Heritage might offer the only truly global platform to showcase the world’s most famous archaeological sites to a global public, but it has had minimal impact upon the history of our discipline. I wanted to understand why. I soon discovered that archaeologists, like many other scholars, had no great admiration for the organization and are more likely to summarily dismiss, misrepresent, or criticize UNESCO and its World Heritage List than to acknowledge its achievements. Educating ourselves about UNESCO then seemed to me the first step, and this project began as an exercise to understand the workings of World Heritage. It was nothing short of a discovery to find that the discipline of archaeology was originally part of UNESCO’s early intellectual momentum and had even extended back to its illustrious predecessor, the League of Nations. And while there was an archaeological component to UNESCO’s famous Nubian Monuments Campaign to save and study the sites and temples in Egypt and Sudan scheduled for submersion with the completion of the Aswan Dam, this was short-lived.

Many critical accounts and analyses of UNESCO have been written, coupled with official histories and narratives by well-placed insiders. Together they tell the story of an imperfect organization that began with midcentury optimism but rapidly devolved from an assembly of statesmen to a tyranny of states. Originally a globally oriented organization, UNESCO was transformed into an intergovernmental agency, a mere shadow of its former ambition for a world peace and mutual understanding between peoples. The overreach of powerful governments has come to permeate all aspects of its functioning. This is reflected in the workings of many of its high-profile programs, including World Heritage — the program that seeks to identify, protect, and preserve outstanding cultural and natural heritage sites around the world. While there are considerable problems, as this book reveals, they should not detract from UNESCO’s achievements in creating a planetary concern for heritage preservation and its ability, however circumscribed, to exert pressure on its member states to honor the treaties that they have ratified.

I would like readers to look closely at UNESCO’s high-profile Nubian Monuments Campaign, coming as it did right after the disastrous Suez crisis. In the twilight of empire, during just over a week in late 1956, Britain and France followed Israel in invading Egypt. The three nations colluded to wrest the Suez Canal from Egyptian control and remove Gamal Abdel Nasser from power. With the major powers again poised on the brink of war and set against the backdrop of the Cold War, Arab nationalism, and Arab–Israeli tensions, UNESCO attempted its most monumental project of global cooperation. The Rescue of the Nubian Monuments and Sites (1959-1980) fully realized UNESCO’s central message of world citizenship from its very bedrock. It paired the ideals of the liberal imperialist past and its cultural particularism embodied in ancient Egypt with UNESCO’s own inherently Western promise of a new scientific, technocratic, postnational future.

So much has been written about UNESCO’s Nubian Monuments Campaign over the years: from the heroism and humanism promoted by the agency’s own vast propaganda machine to the competing narratives of national saviors, whether French or American; from Nubia as a theater for the Cold War right down to individual accounts by technocrats, bureaucrats, and archaeologists. Therefore, it would seem that there is little new to say. Yet if one recenters UNESCO’s foundational utopian promise, couples it with its technocratic counterpart, international assistance, then adds the challenge of a one-world archaeology focused on the greatest civilization of the ancient world, we might produce a new slant on a future in ruins.

As the adage goes, if UNESCO did not exist, we would have to invent it. Without its contributions in the fields of education, science, and culture it is all too easy to imagine a world in ruins.

Yet despite their initial good intentions, many international organizations like UNESCO are struggling or have failed to implement their vision to improve the lot of great swathes of the world. Whether in the fields of environment and climate change, economic development, global health, or human rights, the impediments to international organizations are most often their member states. Perhaps it should not be surprising then that World Heritage has become so contentious. Culture and heritage are supposed to constitute a benign forum for soft power negotiations, but in fact they are intimately sutured to identity, sovereignty, territory, and history-making, with ever more fraught and fatal consequences. As UNESCO’s highly visible flagship program, the stamp of World Heritage may prove to be both the source and the solution to that dilemma.

UNESCO’s appeals to one-worldism and universality were ambitious and legible in the aftermath of a world war. For better or worse, the commitment that UNESCO embodies has been accompanied by an unshakeable confidence in the possibility of human improvement and an optimistic adherence to its mission.

Perhaps the real and unstated problem is that we imagine international organizations to be more powerful than they really are and expect them to deliver on impossible promises. Collectively we expect that they can be better than we can as individuals. The utopian dream of UNESCO, while not fatally flawed, was nonetheless tainted by the same human history and politics that it sought to overcome. Emerging from dystopia, the organization would advance its mission over the next seventy years in the best of times and the worst of times.

Lynn Meskell is Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Stanford University. She is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. Over the past twenty years she has been awarded grants and fellowships including those from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the Australian Research Council, the American Academy in Rome, the School of American Research, Oxford University, and Cambridge University. She is the founding editor of the Journal of Social Archaeology. Recently she conducted an institutional ethnography of UNESCO World Heritage, tracing the politics of governance and sovereignty and the subsequent implications for multilateral diplomacy, international conservation, and heritage rights. Her current fieldwork explores monumental regimes of research and preservation around World Heritage sites in India and how diverse actors and agencies address the needs of living communities. Given the sheer scale and complexity of archaeological heritage in India, no nation presents a more fraught and compelling array of challenges to preserving its past.