Four Metaphors of Modernism follows artists, who participated in the German organization Der Sturm (the storm) and the American organization Société Anonyme (anonymous society), and who found inspiration in metaphor. Beginning with Herwarth Walden’s Der Sturm (the journal, gallery, performance venue, press, theater, bookstore, and art school in Berlin, 1910-1932), I trace Walden’s aesthetic and intellectual roots to the composer Franz Liszt and the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche—forbears who led him to embrace a literal and figurative mixing of the arts. Then I follow many artists across the Atlantic to Marcel Duchamp and Katherine Dreier’s Société Anonyme in New York (1920-50), for it is a little-known fact that the founders of the Société Anonyme based their organization’s practices on those of Der Sturm.

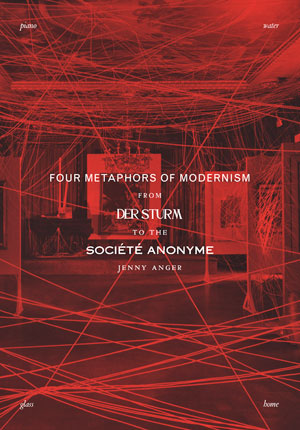

The book is a chronological excavation of the histories of these intertwined arts organizations and at the same time an exploration of the metaphors central to their creative output. Each chapter considers one of four metaphors—piano, water, glass, and home—as it evolves at Der Sturm and then at the Société Anonyme. Each of the chapters retells the history of the organizations from the perspective of a different metaphor. They can be read in any order, although piano came to prominence first, followed by water, etc.

More specifically, we learn in “Piano” that Walden’s earliest piano compositions, written for the poet Else Lasker-Schüler, demonstrate his penchant for an aesthetics of empathy and response. Walden admired the painter Wassily Kandinsky, who himself wrote about artistic communication with the extended metaphor of the piano. Marcel Duchamp and Katherine Dreier used the piano to mediate and problematize relationships.

“Water” features Alfred Döblin’s Conversations with Calypso, a foundational aesthetic of Der Sturm, in which music is likened to water. Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter, Kurt Schwitters, Duchamp, and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven reveal their joy and ambivalence about autonomy and relationship in their aqueous works in Germany and the United States.

“Glass” reveals that Der Sturm published Paul Scheerbart’s groundbreaking treatise Glass Architecture and supported Bruno Taut’s revolutionary Glashaus (glass house). However, neither project subscribed to modernism’s purported ideal of transparency. Rather, the metaphorical possibilities of translucent glass inspired Scheerbart, Taut, Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Paul Klee, and László Moholy-Nagy—the latter two also at the Société Anonyme.

Finally, in “Home” we learn that sociologist Georg Simmel formulated some ideas about gender, art, and home while lecturing for Walden. Adolf Loos’s homes shuffled public and private, and the First German Autumn Salon highlighted Sonia Delaunay’s domestic art in Berlin in 1913. Is it any wonder that the Société Anonyme’s 1926 Brooklyn exhibition included staged “rooms” for art? A “Reprise” finds startling and unexpected resonances in the work of later American modernist Jackson Pollock.

The book argues for a new paradigm: only in considering Der Sturm and the Société Anonyme together, can we grasp the extent of their respective influences on Euro-American modernism; both decenter Paris as the capital of modern art. I also argue for the unacknowledged centrality of metaphor in modern art through an exploration of four recurrent metaphors that shape the realm of possibility of art in these intertwined networks. Consideration of metaphor returns allusion and the real to modernist abstraction—a field long thought to be pure and devoid of reference. This re-envisioned modernism, in turn, is more feminine, intermedial, and relational than has been previously understood; the modernist principle of masculine, medium-specific autonomy all but disappears here.

How did such a book come about? My dissertation, followed by my first book, Paul Klee and the Decorative in Modern Art, pointed me toward this project. I was interested in Klee’s early career, and I learned at the Sturm archive at the State Library of Berlin that it took off under Walden’s tutelage in the 1910s. At the same time, I was impressed by the immensity of the Sturm collection, which I was fairly certain had not been studied thoroughly by scholars writing in English. Many years later, I had my hands full studying Der Sturm alone when I discovered its ties to the Société Anonyme. I felt these connections were imperative to pursue, especially because the American angle might appeal to American readers. The addition of the Société Anonyme added a few years to this book’s writing, but I think it tells such a rich story that it was worth it. Indeed, the extra time allowed the metaphors I kept coming across to crystallize in my mind, such that I decided to eschew a conventional historical narrative and, instead, frame each section with a pressing metaphor (which is to say that there were others that felt less urgent and did not make the cut).

I hope that a potential reader would flip through the book and find unexpected images or startling juxtapositions thereof. He might ask why a more familiar modernist painting by Kandinsky is in a book together with one by a virtual unknown, the Dutch Jacoba van Heemskerck, who exhibited actively with both Der Sturm and the Société Anonyme. (Both organizations promoted more women than is commonly known.) She might wonder, for example, why an interior of Bruno Taut’s Glass House is paired with a watercolor by Paul Klee; if she pursues the heading “Glass,” she would discover that these works in different media were similarly inspired by the utopian possibilities of translucent glass. Some unexpected views of potentially already familiar works might also pique the interest of the casual reader: why, for example, is Duchamp’s Small Glass shown not against an opaque background for optimal viewing but instead in a home on top of a piano—and positioned just so that it welcomes a viewing relationship with a hypothetical pianist? (It turns out that Duchamp, for all his Dadaist antics, was deeply attuned to the metaphorical and relational aesthetics of glass, home, and piano.) I value close viewing of art objects, so I would hope that the browser might skim the text adjacent to any particular image in the book and discover more than an initial glance at the image could provide.

If my book could contribute to a dismantling of modernism as primarily masculine, autonomous, and French, it will have achieved a great deal. Paris is important, of course, but the thriving networks discussed in the book operated relatively independently of it. Further, it is not that there were not a lot of male artists, it is that many conventionally feminine characteristics were actually welcome, if not constitutive of modernism. This is where my two books come together, because in the first I argued for the essential relevance of the feminized decorative in the art of Paul Klee and modern art at large. In the second book the feminine appears in the emphasis on domesticity but also on the relational quality essential to these artists’ relationships with each other and with their art. Some feigned autonomy, but most actually sought out interdependence. Metaphor highlights and compounds these relations, as you need to “get” what the other (or the art) is presenting literally and figuratively. You need to adjust your understanding and expectations to the presented model and passively accept it before you can actively assert something else. Metaphor is not autonomous. Awareness of the relational, finally, renders the contributions of more women artists visible.

A corollary would be the debunking of the belief that abstraction is pure and wholly independent of the world in which we live. A lot of the art in this book is abstract, and all of it is indebted in one way or another to metaphor. Metaphor is always a double register, and abstract art is too. Abstraction is not about itself; it is an analog of the real world. It is a metaphor.

Finally, I would be pleased if architectural historians paid closer attention to translucence instead of assuming universal validity for transparency. The terms are relevant again today, so the non-specialist might pay heed to them in this context. Our culture values transparency, yet it might behoove us to approach the concept more cautiously, because its promise of complete openness and revelation also entails a compromise of privacy, if not the reality of surveillance. Modernists wrestled with this conundrum, finding their freedom in translucence, and we might have something to learn from them.

Jenny Anger is professor of art history at Grinnell College. Her book, Four Metaphors of Modernism: From Der Sturm to the Société Anonyme (University of Minnesota Press, 2018), which is featured in her Rorotoko interview, examines the centrality of metaphor in the creative output of both arts organizations, arguing for a reassessment of modernism in general. Her first book, Paul Klee and the Decorative in Modern Art (Cambridge University Press, 2004) explored the critical role of the decorative in that artist’s career and in modern art. Anger received her M.A. and Ph.D. from Brown University.