Twenty years ago, if a leader from a country like Nigeria looted billions of dollars from his own country and stashed the money in the United States, the US had no moral or legal duty to do anything about it. Now, however, there is an international, moral, and legal rule prohibiting one country from hosting money stolen by the leader of another country. In response, the book asks three questions. First, why is there a new prohibition on hosting foreign corruption proceeds? Second, how well does this new rule work? Third, given that there is still a lot of this kind of dirty money crossing borders, how could we make this rule more effective?

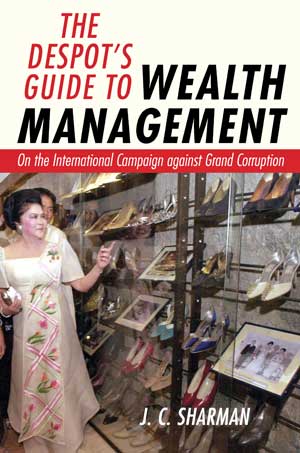

Most studies of corruption are about how money is taken; this book is about where it ends up. The kind of corruption I am interested in is kleptocracy. Literally, in a ‘rule by thieves,’ leaders and their families take huge sums of money from the countries they rule, often further impoverishing some of the poorest populations in the world. Usually, most of this money does not stay at home. Instead, corrupt rulers either spend or stash their ill-gotten gains in places like London, New York, or Switzerland. The new rules aim to break this cycle of looting, laundering, and under-development by following the money trail, seizing illicit wealth, and trying to return it to the victims.

In The Despot’s Guide to Wealth Management, I argue that the new rules to counter kleptocracy potentially represent a huge change. Many, perhaps most, state leaders are corrupt, so the world effort to hold them accountable is a sea-change in the conduct of diplomacy and international politics. But the gnawing doubt is that the rules aren’t really working. Leaders are continuing to steal, and their tainted funds are still ending up in the four host countries that I studied in detail: the United States, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Australia.

A basic point of both curiosity and frustration that motivated me to write the book is the difference between rules in the rule-book and what happens in practice. In theory, considering the detailed and exacting international and domestic laws and regulations designed to keep kleptocrats from laundering the proceeds of their corruption abroad, the problem should have been solved.

Yet, year after year, scandal after scandal, the dirty money somehow seems to slip through the net, and corrupt leaders escape accountability. In 2011, the Arab Spring revolutions revealed not just how spectacular the corruption of the former rulers of Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia was, but also how much of this wealth they were able to move into major Western financial centres. Current leaders of highly corrupt African and Central Asian countries continue to live well beyond their means, and both they and their suspiciously bountiful assets travel freely. How can the big gap between what ought to be happening (or ought not to be happening) and the reality be explained, and how can the gap be closed or at least narrowed?

As a student of policy and politics, I wanted to know why the promise of a system that looked so good on paper seemed to be so hard to translate into practice. This followed earlier research I had done on tax havens and tax evasion, and anti-money laundering more generally. All these problems epitomize challenges of globalization, whereby states and other actors struggle to impose control on an increasingly borderless financial system.

In terms of answering the big questions, I see the new rules against grand corruption as a product of the end of the Cold War and the failure of development policy. The collapse of the Soviet Union undermined the rationale for the US and other Western countries to prop up thoroughly corrupt but staunchly anti-Communist client regimes. At about the same time, the World Bank and other development institutions had to explain why their policy prescriptions had failed to make poor countries richer. Their response was that corruption had prevented development, and thus that to achieve the latter it was necessary to fight the former.

Although there have been some important successes in the fight against grand corruption, overall the results have been disappointing, for a number of reasons. First, international law enforcement and judicial co-operation across borders is just an inherently difficult process, especially when it comes to complex financial crimes. Second, the bureaucratic incentives faced by prosecutors and police favour simple, quick cases with a high probability of success, whereas major cross-border corruption cases are complex, expensive, and drag on for years or even decades. Finally, many key monitoring and enforcement functions have been delegated to banks and other private intermediaries whose interests are often best served by turning a blind eye to clients with suspicious wealth.

Of the four host countries I studied—the US, Britain, Switzerland, and Australia—the last one seems like the odd one out. Aside from the fact that I am from there, Australia was important as the dog that didn’t bark, i.e. where the government wasn’t even trying to investigate whether there were foreign corruption proceeds in the country. The Australian government’s position was that there is simply nothing to investigate, because there is no foreign dirty money down under. (In contrast, though they are facing many obstacles, the governments of the other three countries are at least making genuine efforts to find and return foreign corruption proceeds.)

In order to sustain my hunch that the Australian government’s claim was wrong, I hired a private investigator experienced in financial crime to look for suspicious money, especially in the Australian real estate sector. Thanks to detailed property records that are searchable online, it was possible to match a list we compiled of senior foreign officials who were accused of serious corruption crimes in their home countries, with their real estate investments bought with tainted funds in Australia. These individuals’ social media profiles were often crucial in connecting the dots.

Thus, contrary to the complacent public position of the Australian government, we found that dozens of foreign officials accused of serious corruption crimes had recently bought property and invested suspicious funds in Australia. Rather than representing any inherent Antipodean virtue, or the absence of tainted funds from abroad, the lack of investigations is a cynical political judgement to let sleeping dogs lie.

In addition to explaining where the new system of rules designed to combat foreign kleptocrats’ laundering came from, and the problems with the way it works, I make some suggestions as to how the system could work better. Some of these recommendations are directed to governments, but in general I argue that non-state actors can make the biggest improvements to effectiveness.

Recent progress in the fight against international tax evasion has important complementarities with the campaign against international corruption, but too often these efforts are isolated from each other. As noted, governments have largely delegated financial surveillance and due diligence to the private sector, especially banks, but then have generally failed to supervise and sanction these financial intermediaries, especially outside the United States.

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of countering corruption is that the only parties that know about the crime profit from it. Anti-corruption policies often boil down to efforts to counter-acting the profit motive, either by creating punitive disincentives (going to jail for taking a bribe), or through appeals to principle (serving the public good rather than selfish private interests). But I argue that we need to turn the profit motive from an enemy into an ally in the fight against corruption. How might this be done?

Whistle-blowers are one of the main sources by which corruption scandals come to light. These individuals often taken huge risks in telling what they know; they should be rewarded for doing so with a share of the penalties levied. One of the particularly disappointing aspects of the efforts to recover assets stolen by leaders overthrown in the Arab Spring was that governments from states like Egypt not only failed to get their money back, but they also racked up huge legal bills in doing so. Yet it should be possible to hire law firms to do the job on a contingency basis: if they recover stolen assets for the victim government the firm gets to keep a share, but if the effort fails, the law firm bears the entire cost.

Though it is natural to think that only law enforcement can undertake investigations, most of the advanced accounting and legal skills that are needed to follow the money trail are in the private sector. These highly-skilled individuals and the firms they work for are motivated by profit, so the question is how to align incentives so that these capabilities can be fully engaged in the hunt for stolen assets. Those squeamish about the idea of anti-corruption for profit should think harder about the costs of corruption, and our modest record of success so far in addressing this problem. In this struggle, we need all the help we can get.

J.C. Sharman is the Sir Patrick Sheehy Professor of International Relations at the University of Cambridge and a fellow of King’s College. Earlier, he worked at Griffith University, the University of Sydney, and American University in Bulgaria. Sharman’s research is focused on the regulation of global finance, especially in relation to money laundering, tax, corruption and offshore financial centres, and the international relations of the early modern world. His latest books are The Despot’s Guide to Wealth Management (Cornell University Press, 2017), which is featured in his Rorotoko interview, and International Order in Diversity: War, Trade and Rule in the Indian Ocean (Cambridge University Press, 2015).