Students do a lot of non-learning in school. They cheat, cut corners, cram, forget everything as fast as they can, and are often miserable in the process. This is a waste, a crying shame. But they are often excellent at learning outside school, because humans are terrific learners. I have concluded that the more school resembles the ways we learn outside school the more successful and engaging it will be.

I noticed that students were really good at learning what they wanted to learn and were really not invested in a lot of what I asked them to learn. So, I wanted to understand better. For about 15 years I’ve been using anthropological approaches to see how people learn in general and how that contrasts with how they learn in school. I have come to realize that the ways people learn in school don’t match the ways we learn in life in general.

I argue that if we are going to keep everyone going to school and if we really want them to learn, we need to change the motivation structure, the assessments, the activities, the goals. It can’t be that we lecture to passive students who regurgitate the information in a test and promptly forget it. This is not learning. It is a simulacrum of learning. To be learned, material has to be used.

This critique of school has roots in John Dewey, and progressive education, in the sense that we should be preparing students to engage in learning for life, but also in ideas of Paolo Freire and his notion of education for empowerment. The critique of industrial education, training docile workers for factory jobs, is old. But schools for the most part haven’t changed. And the lecture system from medieval times when book ownership was limited so the lecturer spoke the contents of the book he—it was always a he—possessed is still the paradigmatic model of school. We obviously don’t need that any more.

What do we need? There are lots of experiments in every corner of the education world, from flipped classrooms to problem-based learning to badges to internships to clickers to theses. Sometimes faculty are afraid to use them, though, because they’ll get dinged on evaluations.

Good students are doing what they’ve been trained to do. From early childhood, they have been trained to focus on grades, on pleasing teachers, on following instructions, on getting points in what I call the game of school. Achievement is the measure.

But it has all kinds of negative side effects and this must be attended to. Attention must be finally paid, to quote that great philosopher queen, Linda Loman, Willy’s widow in Death of a Salesman, to “such a person”: every single human being who comes our way.

The topic of this book is connected to everything! (Okay, maybe not directly to geology or health insurance. But to a gazillion other things that matter.) It’s connected to the nature of humans as social and learning animals with long childhoods; to the political and economic structures that intersect with schooling and credentials; to families and the roles of youth; to ideas of cultural transmission; to the question of wellbeing and how school contributes to or undermines it; to feelings of worth; to the human mind in its fully capable essence; to work, obviously; to joy; to international competition and perceptions of international competition; to democracy.

My book is fully anthropological in the sense that anthropologists have studied learning around the world. Until schools spread in the second half of the twentieth century, learning in life rarely resembled what has become familiar to us: divorced from real life, with age segregation finely sliced, with every foray into learning measured and evaluated, all mistakes punished and averaged together, and the material imposed because it is related in some theoretical way to some uniform sense of what students are likely to need at some point in the future, probably in the next round of schooling.

Since just about everybody now goes to school, if not to higher education, this affects everybody. But not everybody is like me. I have always LOVED school. I thrive when I learn abstractly.

Most people don’t. And that’s okay. There’s not just one way to be a person, and there’s not just one way to learn. My cultural relativistic ideas from my anthropological background did not necessarily lead me to think this, until I had a kind of crisis in my teaching, where I really dreaded going to class. In the end, I changed from blaming the students to blaming the structure—including the structure I imposed in my class.

I had written about plagiarism, building on work I’d done on truth and deception in China and elsewhere. It connects with my training in China studies, and with my focus on linguistic anthropology. But this latest book—the second in a trilogy—really takes on the nature of schooling, which was only one of the components of students’ willingness to resort to cheating and plagiarizing. If the whole goal is the grade, then any means is as good as another. If the goal is learning, then things like writing matter. But students are shaped by the conversations that surround them, and most people talk only about the “bottom line”: GPA, degree, time to completion, statistics about school attendance, etc. The assumption is that all this matters because somewhere in between signing up for a lifetime of debt and finding a job, there is some energy left for learning. But in fact, there isn’t that much.

I find that deplorable, but now completely understandable.

So, I invite my students to join me on an adventure in learning, with lots of choices and options to connect it to something that matters for them. I’ve developed a thoroughly ecological view, following John Muir’s insight that “ When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” So if a student in a Food and Culture class is interested in something—eating disorders, Instagram photos of food, notions of Ukrainian food, acai and other superfoods—then our themes of identity, gender, power, representation, aesthetics, taste, marketing, and cultural influence will emerge. I am confident that students can lead and then we will find what they need to get to their place.

My understanding of the nature of humans has increased—which is completely part of my training as a cultural, linguistic, and psychological anthropologist, even if the specific questions and domains within which I address them appear completely unrelated to my first academic work. My involvement in a holistic, integrative department of anthropology, where I have conversations with colleagues specializing in biological anthropology, has influenced me profoundly.

I read like a fiend; I’ve pretty much used up my eyesight.

And I have learned most everything from listening to my students and my own daughters.

I have to confess that I like this book. I poured my heart and soul into each page. I lived with the ideas and the sentences and the chunks for years. But some of my children are more beloved than others. (And yes, like all writers, I’ve learned to “ kill my darlings.” There is a lot that has been excised.) But if you want to poke around, here are a few places to amble:

The Introduction, especially pages 1-6, 15-16.

The strangeness of higher education, pages 86-88 and 113.

Chapter 5 on grades, which is something I’ve become entirely obsessed about.

Pages 181-189 on the nature of the human animal.

About riding a bicycle, pages 209-210, because I remember writing this passage in one burst.

Chapter 9 on motivation, especially Table 9.1 on page 222.

The Conclusion, especially pages 270-274.

I tried to tell the story of my journey: I had been one kind of person and teacher, had a crisis of understanding, did research, changed my mind, and became a different kind of person and teacher. If you flip through those pages, you’ll get the gist of the story.

This book—the inception, research, writing, conversations, reception—has completely changed the way I think about my profession. I had become disillusioned and cynical, mostly about students. Now I’m more disillusioned with the entire conventional model of higher education (and other levels as well). But I’m hopeful too; there are great ideas about how to work with the inherent curiosity and need for meaningful engagement that just about everybody has. I’m not focused on merit, or sorting, or intelligence. I focus on, fixate on, obsess about meeting each student where they are. That is my responsibility. Just as in traditional societies everybody has to learn to weave or cook, so in ours everybody has a right to expect to be aided in their learning.

If I could have a wish, it would be that students, parents, the public, administrators, and faculty would focus on how to get students to plunge into meaningful learning when it matters to them, and to work with them to define their goals and then help them realize them.

If you want the full picture of what I envision, read the appendix where I compare education to permaculture, the approach to working with the environment to minimize waste, to produce in accord with natural tendencies, and to create a livable planet with livable lives, where we maximize harmony and efficiency without trying to overcome nature. Humans are by nature learners; surely, we can work with that in our schools if only we try.

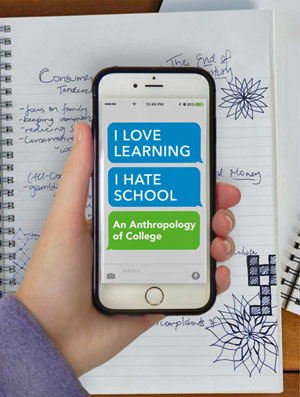

Susan D. Blum is professor of anthropology at the University of Notre Dame. She has written and edited eight books and dozens of articles and book chapters, on topics from Chinese ethnic and linguistic diversity to ideas of truth and deception, from college plagiarism to the so-called language gap, from local food to the nature of learning. She has taught at several universities over the past nearly 30 years, and is embarking on a radical transformation of her own teaching as a result of the research summarized here.