Quarks to Culture involves a new, big picture perspective of the universe. Now, by universe I do not mean the astronomical cosmos that the word usually refers to. I mean our lived universe. This includes living cells. It includes the works of all cultures. We might call this expanded universe the universe of all things.

What kind of new perspective? If we go down in scale into the human body and look at the kinds of systems we know about, it is like going back in time. Our bodily cells as living cells, as members of a type of system, came into existence well before bodies, such as we animals who are made of trillions of cells. Taking this time machine further downward in scale, we find the kind of thing known as molecules in this universe of all things. Molecules as a kind of fundamental thing came into existence, indeed, had to come into existence, before living cells.

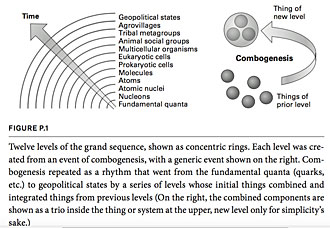

So, in the questions I asked that led to this work, I wanted to find out if I could discover fundamental levels of kinds of things. I wanted to discern these levels with a consistent logic. I return here to the time machine just noted as one goes back downward inward in scale. Might one start with the simplest entities known to science and build up in a logical sequence from small and simple to large and complex? The logic involves a recurring pattern in time, in which prior existing things combined and integrated into larger things. At each level of larger things, the pattern or process repeated: those larger things now became the prior existing smaller things that combined and integrated into the next level of larger things.

When one follows this logic, as I hope to have done, or at least proposed, twelve fundamental levels emerge: Level 1 Fundamental particles; Level 2 Nucleons; Level 3 Atomic nuclei; Level 4 Atoms; Level 5 Molecules; Level 6 Prokaryotic cells; Level 7 Eukaryotic cells; Level 8 Multicellular organisms; Level 9 Animal social groups; Level 10 Cultural webs of “we”; Level 11 Agrovillages; Level 12 Geopolitical states.

There is more. Each level contains things that are fundamentally new, because innovations in the relations of the things at each level were necessary to create the things at the next level, at least in our universe of things. This remarkable and special sequence I call the grand sequence.

I have written the book so that readers are walked through the essential, best currently known science and scholarship of the things at each level, the innovative relations, and how those new things and relations led to each subsequent level. That walk takes place in part two of the book, following the general theory of the logic and the quest put forth in part one. Finally, in part three comes what I see as a very exciting part of the book. In part three I treat the levels as a set of phenomena in an attempt at a universal field of scholarship and ask about commonalities or groupings of families within the levels. I will say a bit more about this below.

All scholarship involves being diligent in seeking and finding of patterns. It doesn’t matter what the field is. We might be considering cultural studies, anthropology, botany, chemistry, linguistics: It doesn’t matter. The kinds of patterns, the kinds of relationships, of course differ greatly. That is why there is loads of work to do in all research departments of all universities.

Slightly more than 20 years ago I wrote a book called Metapatterns Across Space, Time, and Mind. I was enthralled with the perception of system dynamics and functionalities that occurred across scales of systems. These functionalities included borders, binaries or two-part systems, the issue of centralization versus decentralization, nestedness of components within systems, and metapatterns of time, such as cycles, arrows, breaks or relatively sudden changes in the structures and behaviors of things. My current book was conceived as a follow-up to Metapatterns, without knowing what I would write. I just knew there was material there waiting to be plucked.

So, I am doing merely what all good scholarship involves. It’s just that I’m taking the field of study to be this lived universe of all things. It might seem a little crazy. But I’ve been teaching metapatterns and writing a few technical articles about them. I was sure that material involving commonalities—really interesting commonalities—was (and still is) there to be found and thought about.

Many of the scholars that I’ve been aware of who do this kind of open scale research use mathematics. I refer to the highly developed forays of mathematics in complexity theory, network theory, fractals, and more. But I’m taking what I like to call an architectural approach. Much has been seen and described, diagrammed and photographed, and understood through the logic of language. In this way, I believe my ideas directly connect to scholarly fields that are not so mathematical.

I recently gave a book talk at a salon held on the first Sunday of every month at the Cornelia Street Café, in New York. (Great jazz there, by the way.) The salon is called “Entertaining Science,” convened by Nobelist in chemistry and all-round amazing man, Roald Hoffmann. Time was very limited because at these Sundays there is also entertainment. I knew I could not go through all the levels to the detail that they really deserve. After all, these levels, I feel, should be—they are—fundamental friends we should all know, in the cosmic sense.

I decided to experiment by flashing through 12 crucial diagrams in the book at about five seconds each. I warned the audience beforehand. I said it’s okay to even laugh. What is Volk doing?

The message I hoped to get across was the same message that a casual reader paging through my book in a bookstore might notice. “Wow, there are a lot of diagrams that look very much the same.” They differ in words, but if placed on top of each other the essential structures look very much identical. And they are.

These diagrams show for each fundamental level how the things of that particular level were made from the merger of prior existing things from the previous level. This is the recurrent pattern or process I noted above, which I have found can take us on a journey of innovation from the simplest things of particle physics to the complexities of culture. I failed to earlier note something I wish now to say. I needed a word for this recurrent process. I am calling it combogenesis. Combogenesis is the genesis of new things from the combination and integration of prior existing things.

So, if you were browsing the book, despite its obvious traverse across a vast landscape of different kinds of scholarship and discoveries, you would visually see there is an integrating—architectural, to use that word again—theme in the work. I note here for the skeptical that for this work I reached out to disciplinary experts who voluntarily, skillfully, and kindly, reviewed chapters that involved their specialties.

Gosh! I hope to connect people in all walks of life to this extraordinarily lively, creative, full of surprises universe that we find ourselves in and which, frankly, we do not ponder in its fullness often enough. Life has demands. Life has distractions. And it requires stretching of the mind to get into all the levels to at least the degree of detail that I think is useful for expanding our minds and such exercise can lead to exhilaration.

I also would like the say in these concluding moments that some of the families of patterns within the 12 fundamental levels can be useful as templates for thinking about the organization of systems that anyone might want to use.

For example, I noted earlier the part three of the book. In that part, I discover, shall we say, or make a case for, three families of adjacent levels that I am calling the dynamical realms: physical laws, biological evolution, and cultural evolution. I will leave it to readers to get into that part, and in particular to see how I justify using the word evolution to refer to certain dynamics within cultural systems, from the upper Paleolithic to the geopolitical state. But the implications of the logic indicate that a next level would be some sort of merger of nations into a planetary scale.

I have an epilogue exploring what this might mean, which I will not go into here. But let me say I believe that new perspectives on the emerging planetary scale can be gained by studying these templates just referred to. You can think of these templates as ways of combining that have been proven successful more than once in the grand sequence. And therefore the templates might be useful as generalizations for exploring possibilities for the planetary scale. This is crucial to think about right now.

Tyler Volk is Professor of Biology and Environmental Studies at New York University. His research involves the global carbon cycle, world energy, the role of life and evolution in the biosphere, and general systems studies. His newest book is Quarks to Culture: How We Came to Be, featured in his recent Rorotoko interview. Recipient of the NYU All-University Distinguished Teaching Award, Volk lectures and travels widely, communicates his ideas in a variety of media, plays lead guitar for the science-inspired rock band The Amygdaloids, and is an avid outdoorsman. Volk’s previous books include CO2 Rising: The World’s Greatest Environmental Challenge, featured in his earlier Rorotoko interview; Metapatterns Across Space, Time, and Mind; and Gaia’s Body: Toward a Physiology of Earth. As to an overarching theme across all these books, he might say, “systems and their mysterious ways, deeply relevant for human life.”