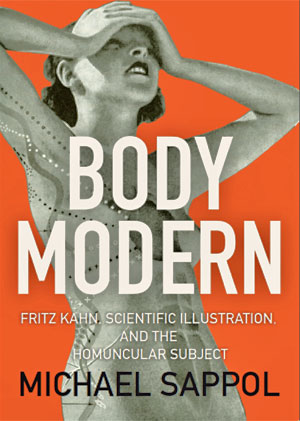

Body Modern focuses on the history of a peculiar kind of imagery of the human body: the conceptual scientific illustration. Primarily found in America and Germany between 1915 and 1960, images of the body modern also traveled to the Soviet Union, China, Latin America, and many other countries, as well as across time; the book follows them to the twenty-first century, where they regularly appear in videos, training manuals, websites, textbooks and magazines—our media environment and experience.

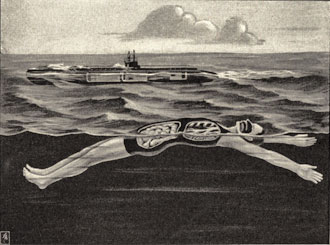

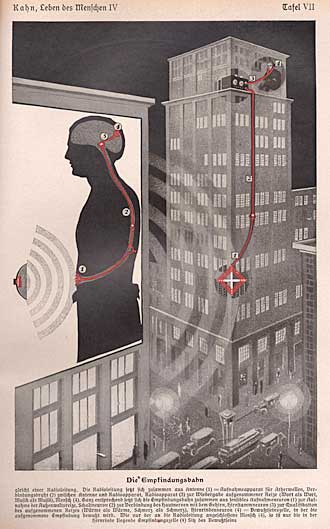

To clarify: Body Modern is not about pictures that teach lessons about the anatomical structures of the body, but about pictures that attempt to entertain and instruct readers with visual explanations of the workings of the human body, using metaphors, sequences, analogies, diagrammatic elements, cross-sections, allusions, playful situations, and juxtapositions. To us, such images seem familiar, something that has always been around, but the genre was novel and remarkable when it was invented in Chicago in the first decades of the 20th century.

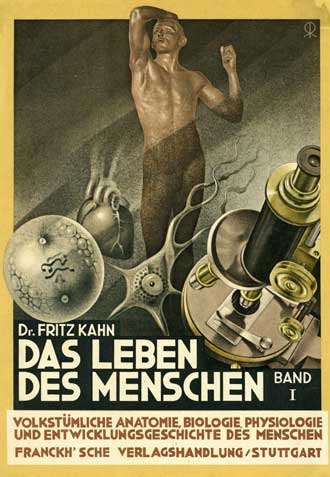

Its first great exponent was Fritz Kahn (1888-1968), a German-Jewish physician and popular science writer. In collaboration with a cadre of commercial artists, Kahn brilliantly deployed and redeployed––he was a great recycler and repurposer of his own pictures as well as those of his predecessors and contemporaries––thousands of illustrations, in books, articles and posters that reached a mass audience in Weimar Germany and around the world.

Body Modern bombards the reader with images from the works of Kahn because Kahn’s pictures were one very remarkable, but now mostly forgotten, part of a pictorial/media regime change, a cultural revolution that aimed to remake the relationship between text, image, and body, and remake, perhaps re-engineer, human subjectivity.

Scholars have long debated modernity, its origins, and its defining characteristics. Body Modern sidesteps those questions. Modernity, it argues, did not descend upon the world like a deus ex machina that re-ordered human consciousness and changed everyone and everything. Instead, Body Modern treats modernity as a historical artifact, the core concept of a 20th-century identity formation.

What makes that tricky is that modernity was a capacious signifier, full of paradoxes. It could absorb anything that seemed to oppose primitive humanity or longstanding tradition, but also anything that opposed the recent past, especially passé versions of the modern. Even the primitive could serve as a signifier of the modern, if it was reframed as a critique of the no-longer-fashionable present, and served up as the latest thing. The modern had to be new.

In the middle decades of the 20th century, a critical mass of people took themselves to be moderns, living in modern times, and felt impelled to live and perform the modern. They sought to cast off local identities and revise traditional ways, to differentiate themselves from what came before. They did that by talking on the telephone, driving cars, wearing modern fashions, reading modern illustrated magazines, listening to new kinds of music on the radio and phonograph, doing new kinds of dances, receiving modern medicines and treatments, going to the movies, taking up new political ideologies, and doing a million other things that signified modern-ness. There was a nearly inexhaustible demand for modernizing devices, objects, methods, presentations and experiences. The public thirsted for the modern.

In this environment, Fritz Kahn pioneered a new kind of image: illustrations that were scientific, metaphorical, and self-consciously modern. In a hyper-illustrated age––where the very abundance of printed half-tone images was itself a signifier of modernity––Kahn’s books on the science of the human featured thousands of illustrations in a variety of modern styles and techniques: surrealism, Art Deco, photomontagery, Bauhaus functionalism, abstraction, Neue Sachlichkeit, sequential art, everyday commercial illustration, etc.

It was a novel and iconophilic approach to popular science, inspired by the media, styles, and genres of the time, especially the illustrated newspaper and magazine. Materials that could help people acquire and perform a “modern” social identity were in demand. Kahn presented himself as an impresario of the modern, a provisioner of images to get modern with. His images were a visual rhetoric of modernity, full of representations of science and technology. More than that, the images themselves worked as a kind of a technology of the self, a modern rhetoric of visuality, which naturalized modernity by situating it within the human body.

Before Body Modern, I had mostly focused on the earlier history and cultural politics of anatomy. In A Traffic of Dead Bodies (2002) I argued that, in the 19th century, under the influence of mass-produced illustrated anatomical publications and popular exhibitions, the American and European public began to develop an anatomical consciousness and identity. People began to think of themselves as anatomical beings, endowed with a geography of parts and boundaries and systems, which were archived as illustrations in books and charts, and as specimens in museums. This anatomical image came to stand as an “effigy of self,” a figural shadow identity, an icon of the real “me,” even if most people had nothing more than a hazy knowledge of the details. For anything more than that they deferred to doctors and surgeons and scientists, who increasingly assumed a position of cultural, moral, and even legal authority over the human body and embodied life.

All that was very modern in the 19th century. But modernity is a moving target: what’s modern in one generation, is old-fashioned in the next. When I came upon the mid-20th-century works of Fritz Kahn, that complicated my story. Kahn argued that the older style of anatomical illustration, which showed detailed images of body parts and systems, was no longer scientifically or stylistically adequate for modern readers. A new type of image was wanted: one that conveyed the latest findings of “modern biology” and could show the dynamic forces at work in and upon the human body: a dynamic image that sparked the enthusiasm of the modern reader.

Kahn’s best-known work, the life-size 1926 color poster, “Der Mensch als Industriepalast” (“Man as Industrial Palace”), did exactly that. It visually explained the workings of the human body by representing it as a shiny factory complex, full of electrical, mechanical, and chemical processes operated by a force of little workers and managers.

Body Modern argues that the homuncular image––in philosophy, a tiny person inside the body or the mind is termed a homunculus––is a hall of mirrors, creates mirror effects. In some incalculably cognitive fashion, we recognize ourselves, and internalize the idea that political economies and arrays of technological devices are inside of us, just as we are inside of the technological and social arrays of the larger industrial world. The printed image becomes for us a homunculus, an effigy of self.

We are shaped and influenced by an environment that is full of representations of the human, and full of other humans who are shaped and influenced by representations of the human, and who carry those representations along with them, into all of their interactions. And at the same time, we ourselves provide the same service for others: we are simultaneously homuncular objects and subjects. The human is in the image, the image is in the human.

Body Modern is a labor of love, a long-time obsession. Fritz Kahn’s prime directives are now our everyday common sense, the prime directives of our civilization: You can’t just say it, you have to show it… And when you show it, you have to put on a show… Body Modern is my show.

I began research on it, under the working title “how to get modern with scientific illustration,” way back in 2005. Over the years, the writing was much delayed due to professional and family obligations, a crazy international romance, and then a long period of liver disease and declining health. In 2011, when I was diagnosed with liver cancer, it looked like that would be the end of me and the end of my project. But in 2012, I received a liver transplant. And in 2013, I was able to resume work.

As the book neared completion, my editor worried the book would be mistakenly shelved in the “how to” section. That pushed me to switch the title to Body Modern, which better conveys the spell that Kahn’s charming new images cast over readers who thought of themselves as moderns, and who aspired to get even more modern. (I could have just as aptly titled it Picture Modern, because those same readers were drunk on the proliferating images that called out to them from illustrated books, newspapers, magazines, posters, and movies. But that wouldn’t have been nearly as sexy.)

“Man as Industrial Palace” uses a doll-house cross-section profile, with a sequence of multiple images within the image, to model the self in industrial modernity. It was a commercial and critical success, and became Kahn’s signature work. But Kahn well knew that the public appetite for images, and for novelty, was voracious, insatiable. He and his artists (“studio of Kahn”) went far beyond, were inspired to develop many other genres and tropes of visual explanation: the body flow-chart, the fantastic voyage inside the body, the dramatized body statistic, the architectural body, the modular body, the global body, the mixed media body, the radiant body, the visual synopsis, and so on—all richly and often humorously imagined in a variety of modern styles.

Those images today come to us as an obscure and complex corpus of modernist image production, a relic of a larger vernacular modernism that scholars of modernism have mostly overlooked. But in their day, the images spoke to a mass audience. Readers got to see modern machines and cities and buildings and science and aesthetics—and themselves—all in the frame of a single image, and in many images, and in many sets of images. An impossible variety of figures, all under the sign of the modern.

Body Modern makes a variety show out of that only partly coherent corpus, and provides 21st-century readers with close readings of selected images and their genres and contexts. And then uses those images to think aloud about the cultural work that prolific representations in bulk did to 20th-century readers and, in a different way, do to us. Because, if we are inhabited and explained by figures and forces and devices, and if we inhabit them back, then the territorial singularity of the individual self—a hallmark of modernity in its “classic” high industrial phase—falls to pieces, becomes utterly undone. The sharp boundary between embodied life and technology and industry and representation and collective groupings of humanity is impossible to maintain.

And so, “Man as Industrial Palace,” an icon of Weimar technological optimism, now graces the cover of the most recent English translation of Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus, an iconic ur-text of postmodern critical discourse. And, along with many other pictures from the studio of Kahn, serves as an object lesson in a brand new essayistic work of history, Body Modern.

Michael Sappol lives in Stockholm, Sweden. For many years, he was a historian, curator, and scholar-in-residence at the U.S. National Library of Medicine. His work focuses on the history of anatomy, death, and the visual culture and performance of medicine. He is the author of A Traffic of Dead Bodies (2002) and Dream Anatomy (2006) and co-editor of A Cultural History of the Human Body in the Age of Empire (2010). His latest book, Body Modern: Fritz Kahn, Scientific Illustration and the Homuncular Subject, is featured in his Rorotoko interview. Two new projects, “Anatomy’s photography: Objectivity, showmanship and the reinvention of the anatomical image” and “Queer anatomies: Perverse desire, medical illustration, and the epistemology of the anatomical closet” are in the works.