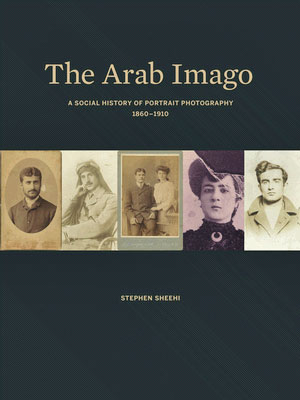

Arab Imago has a dual personality. It explores the undiscovered history of indigenista, or indigenous, photography of the Arab world. I am particularly interested in the earliest decades of photography, specifically, nineteenth and twentieth century studio portraiture in Arab, or, at least pre-1914, Ottoman photography.

Dedicated exclusively to native photography, the book offers new information about lesser known photographers from Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt, such as Jurji Saboungi, the Kova Brothers, Garabed Krikorian, Khalil Raad, Muhammad Sadiq Bey, and Ibrahim Rif’at Pasha. The book also revisits and offers an original reading of well-known Ottoman photographers, who operated both in Istanbul and Cairo, such as Abdullah Frères and Pascal and Jean Sébah.

The book’s alternate personality is theoretical. It develops a theory of reading photography and shows how integral “non-Western” photography really is to the history of photography as a whole. A theory of reading portraiture, then, may be able to cross borders and boundaries and take into account the specificities of social, political, and visual histories of particular photographic practices.

Considering the mass of uncharted material, I chose to focus on photographic portraiture, mostly produced in the studies of Beirut, Cairo, Alexandria, Jerusalem, and Istanbul. But the theoretical arc bridges a number of different genres of photography. While the book is dualistic, it is also integrated, and I would hope that readers see how the material and social history of photography in the Arab world can be read simultaneously as empirical and theoretical.

When we talk about the history of photography, we largely mean the history of European and American photography. Then, we attach the “other” photographies: Indian, South American, African, Arab, etc. I hope this book will help change that habit. I hope it will help to provincialize European photography by showing the robust and often similar ways photography is used, distributed, and displayed in the Arab Ottoman world.

It is tough because in the attempt to shine light on the histories that live in the shadow of European photography, there is also the threat of exoticizing the practices of the “non-West.” How to get around this? How to remediate the glaring absences of the history of photography without reintroducing the idea that Arabs just mimicked European forms of photography? How to introduce a history without reinscribing the difference of nineteenth century Arab photographs? How to explore unknown and known nineteenth century Ottoman photographers without tripping on standard Eurocentric questions of the field such as “how did the Arabs use photography differently,” or “how does Arab portraiture look different from European portraiture?”

Indeed, I thought through these questions at length, not by avoiding the formalism of the carte de visite and cabinet cards, for example, but by thinking about form, repetition, and standardization of the portrait in ways that function similarly across borders, but also might have different effects in specific social and historical contexts.

Coupling a theoretical framework—one that analyzes issues of identity politics, economic transformations, and social hierarchy in the context of larger systems of power and social formation—with rigorous empirical research on photography, based in archives and written texts, is essential to a holistic study of such a new and emerging field.

The book is divided into two parts. “History and Practice” introduces historical contexts, key figures, and concepts that enframe Arab Ottoman photography. “Case Studies and Theory” animates these theories and demonstrates how they unfold within specific contexts, for example, Ottoman Palestine or Khedival Egypt and Hajj photography.

We need to practice due diligence in understanding the social history and context of photographic production. We need to come up with methodologies and theories to answer questions like “how did photography circulate in the Ottoman Arab provinces?” We need to explore the written archive, the ways in which Arabs talked about photography, how they engaged it, and what photographic practice, both professional and amateur, really looked like. But at the same time, we have to be agile enough to think about what happens when these practices seem to corroborate many of the master narratives of the history of (European) photography.

In response to such challenges, the book shows how to read photography as a material object and as a historical, social, political, and aesthetic document, while also understanding it as a site of photographic representation. This is what I have called its “manifest” form and content. I hope to show how the photograph, in turn, circulated, how it was discussed, and how it was used within Arab Ottoman society. Yet the manifest surface itself and the material object are not the end point. They are predicated on the fact that the image is understood and meaningful.

I also hope to show that photography is always about legibility. What started me on this journey is my own fascination with the fact that the photographic portrait seems to arrive in the nineteenth century already legible. When photography appeared in the mid-nineteenth century Arab world it was certainly accompanied by some degree of discussion. But this discussion was largely about the science behind the practice. Rarely, do we find testimonies of wonder or bewilderment. This made me ask questions like: how was photography immediately understandable? How did it immediately make sense? What was the ideology of the image that seemed to be natural? And, conversely, what are the ideologies, practices, and social realities that were denigrated and demonized, that were locked out of this photographic legibility?

This is what I call the “latent” content. That is, if the manifest content is the surface of the image and what the image clearly means, whereas the latent content is that which operates outside the photographic frame, forcing us to really reach beyond the material object to understand not only its history, but also the history and social context that made it legible.

In this respect, the Arab Imago presents the nineteenth century Arab portrait not as a document of reality or mere artifice. Instead, it presents it as a composite of the manifest and latent, the apparent and the suppressed, which make the photograph an active site of contestation, not a simple window on the reality of its day.

The introduction is a fruitful place to meander and to get a sense of the book. It covers a lot of ground. It also provides a short, traditional overview of the master narrative of the history of photography of the Middle East. It introduces some enframing issues of photographic portraitures and some teasers to the content of the book. It opens with an unknown vignette about the first photograph of the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, taken by Muhammad Sadiq, a Khedival topographer and pioneer photographer of the Hajj.

The introduction is also the place where I recognize my shortcomings, where I could not go, and the spaces left that we need to explore. Namely, I recognize that most of the photographers I studied are male and that there is a larger unwritten, indeed invisible, history of women’s participation in early photographic ateliers. I recognize the central role of Armenians, which I cannot fully access because of language limitations. I also recognize that there are a number of other photographic genres (group portraits, candid photography, scientific photography, amateur photography, etc.) that emerged between 1860 and 1910 that I could not explore.

I believe the implications of Arab Imago are potentially far-reaching, but depend on the field in which it is read. Within Middle East Studies, the book explores the uncharted history of indigenous “Arab” photography, solidly engaging particular photographers as representative of certain practices and certain formalistic features and expressive of important social conditions, realities, and transformations. It locates photography as a social and commercial practice, with political, economic, and cultural effects within the late Ottoman Empire.

Within the larger field of photography studies and visual culture, I do believe that reading the “manifest” and “latent” content of indigenista photography reaches across a number of geographies, traditions, and temporalities. I would like to think that the Arab Imago interrogates the Eurocentric nature of the history of photography, projecting all forms of “non-Western” photography as derivative tributaries to the main source in France and England. Without discounting the power and violence of Orientalist and colonial photography, I hope to show that local photographic practices in the Middle East operated within their own particular contexts even though these contexts are always caught in imperialism’s gravitational pull.

My hope for the Arab Imago is that it will inspire explorations into indigenista photography of the Arab world, and that it will encourage a conversation not only with European and American scholars of photography, but also with scholars of Asian, African, and South American photography. It is only through this truly collective discussion that we can really understand the true nature, hues, and complexities of the history of photography.

Stephen Sheehi is Sultan Qaboos bin Said Chair of Middle East Studies, Director of the Asian and Middle East Studies Program, and Professor of Arabic Studies in the Department of Modern Languages and Literature at the College of William and Mary.