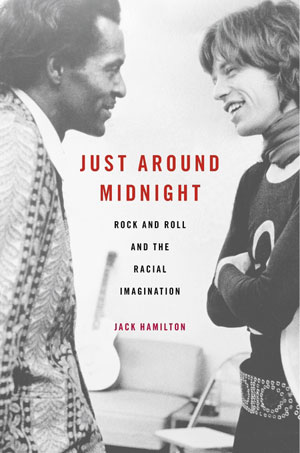

Just around Midnight is about the entanglements of popular music and racial thought during the 1960s, and particularly the question of how rock and roll music “became white.” By the time Jimi Hendrix died in 1970, many of his obituarists found it remarkable that a black man would be playing electric rock and roll guitar, in a way that no one would have thought odd when Chuck Berry was doing it just a decade earlier. My book is about how this happened, and also about how it happened during a decade that’s often thought to be marked by unprecedented amounts of commercial crossover and aesthetic exchange. For instance, you have the extraordinary rise of Motown and Southern soul on one side of the Atlantic, and on the other side of the Atlantic a whole host of bands who “invade” America while having spent their formative years deeply steeped in black American musical traditions, most famously the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. And of course there were individual stars like Sam Cooke, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and Jimi Hendrix himself, all of whom crossed racial boundaries in both their music and their audiences.

All of these artists and entities were described as “rock” or “rock and roll” performers at various points in the 1960s; how, then, did we end up with a notion that rock music is something that only white people do? My book charts this shift, and argues that the real story is one of reception rather than production: in other words, “rock” didn’t become white because of choices musicians made, or because white musicians “stole” the music, or because black musicians chose to leave it behind. Rather, it happened due to the way audiences and writers and, subsequently, marketers and radio programmers and the music industry generally decided that different kinds of people made different kinds of music. The book is an academic book but I’ve tried to write it in a lively and readable style, so that it can reach as many readers as possible. This is music that a lot of people really love—I myself really love it—and at best I’d like to think my book offers us a chance to hear it differently than we often do, and also to correct some of the more tired and ill-founded myths about Sixties musical culture.

There’s been a lot of discussion of “cultural appropriation” in our culture recently—this is obviously a perennial topic but it seems to be a particularly charged subject in the current moment. It’s obviously an incredibly complex and difficult subject, one that resists any sort of easy answers. I’d like to think that my book offers a different way into that conversation by exploring the ways that the identities of people who consume art often come to structure our understanding of that art as much as the identities of the people who make it, which are often more varied and diffuse than we’d expect. I also think we often tend to use artists and cultural works as conduits through which to have debates and conversations that can quickly far exceed the specifics of those artists and works themselves. This can obviously be useful but it also has its limits, and can become obfuscating if it starts to drown out the art itself. This book is about a period when that tendency, which is as old as America itself, became particularly pronounced. So I think the book will definitely hold interest for people who are drawn to broader questions about how race and racial thought interact with culture, and I also think it’ll be of interest to people who enjoy reading about 1960s music, which I’d like to hope is quite a lot of people!

In terms of my professional path, I actually spent a few years as a full-time musician in my late teens and early twenties, which was an incredibly formative time for me, both the experience of playing music for a living and being surrounded by others who’d chosen to do so, many of whom were older than me and came from a wide array of circumstances and backgrounds. Among many other things, that experience left me deeply fascinated by the ways musicians think about what they do, and how musicians approach music-making. After returning to college I worked for a while as a music critic and journalist, which was also a great experience, and left me interested in the ways that music writers think about what they do, and how the venues that publish them frame that work as well. And of course, throughout all of it I was interested in the way the “music industry”—in 2016 that term is so vague and toothless that it’s hard not to scare-quote it, but that hasn’t always been the case—exerts pressures on both these parties, the people who make their living making music and people who make their living commenting upon it.

There are a lot of parts of this book I’m pretty proud of. The last chapter, on the Rolling Stones in the late 1960s, is the one that I’ve been working on and living with the longest, so it has a special place in my heart. The third chapter has an extended section on the influence of Motown session bass player James Jamerson on the Beatles’ Paul McCartney, which is also a personal favorite. McCartney is obviously one of the most famous musicians of the 20th Century, whereas Jamerson might be the most criminally under-recognized genius in all of American popular music. So it meant a lot to give him a moment in the sun—I’m admittedly biased due to my own background, but I always feel like sidemen and studio musicians don’t get written about nearly enough. And in my first chapter I write about Sam Cooke, who’s my favorite singer of all time and another performer who hasn’t received nearly the amount of critical and scholarly attention that he should, in my opinion (although he’s certainly received more than Jamerson). That part of the book is quite special to me as well.

This is probably a boring or obvious answer, but first and foremost I’d really just like people to read the book and enjoy it. Apart from that, I’d like to think it’ll challenge and hopefully change some of the ways we discuss both Sixties music and rock music in general. I really do love all of the music that’s discussed in this book and have no desire to be contrarian or overly critical towards any of it. In many senses I think trying to get to the bottom of some of the ways artists have been misheard is actually a way of shining a light on just how extraordinary their work is, even when it’s people we already know are really great. For instance, writing this book gave me an even deeper appreciation for the music of artists like Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and the Beatles, all of whom are already pretty widely praised! So maybe it’s just the educator in me, but I think my main goal for the book’s consequences would be that people read it and learn from it, and have a good time while doing so.

Jack Hamilton is Assistant Professor of American Studies and Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Just around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination, featured in his Rorotoko interview, is his first book. He holds a B.A. in English from New York University, and a Ph.D. in American Studies from Harvard. He is the pop critic for Slate magazine, and his writing has appeared in The Atlantic, NPR, Transition, ESPN, L.A. Review of Books, Rolling Stone, and many other publications.