What happened in Cuba was basically the collapse of a dream. That’s obvious, but nonetheless painful.

Specifically in the arts, the 1980s was a time of incredibly energetic and critical creativity, the product of a generation of young artists committed to the prospect of true—meaning truly independent—expression.

It was a cohort of artists who were committed to the utopian project of revolution, and who considered it a natural part of their role as artists and citizens to participate critically in that process. After 1989 that all fell apart, along with the country’s fundamental sense of purpose. Yet artists continued to produce.

I began work on the book convinced that the production of the 1990s was a cynical betrayal of the enthusiastic commitments of the 80s, but soon came to realize that the chastening experiences of the 90s were actually the most important part of the story.

Writing this book was, for me—as a child of the sixties—a way to come to terms with the failure of utopian ideas about culture and social change. And more than that, it gave me a way to think through the process of living, without illusions, the experience of disillusionment.

“What happened in Cuba gives us an acute sense of what it can mean, both for individuals and for societies, when we engage in that most contemporary of dilemmas—heading both to and from utopia.”

My own engagement with Cuban art began in 1985, the result of a happy accident. I was immediately fascinated by the work that my peers in Havana were making: it was incredibly rich and diverse in aesthetic terms, and there was a social energy around it that I had never experienced in other artworks.

This was a time when “political art” in the US was largely sloganeering and directed against government policies (e.g., the wars in Central America), and what was happening in Cuba felt much more oxygenated and much less narrowly construed—political in its engagement with real and shared political space, rather than with the ideological surfaces of institutional power.

The “utopia” of the title points in a couple of directions: the dream of a just and equitable society, and that of an artistic practice that has full partnership in that project, without conceding its unique expressive, intellectual and idiosyncratic foundations.

To and from Utopia in the New Cuban Art deals with a pretty broad range of questions in contemporary art, especially ones having to do with the edges at which art intersects with the social and political fabric.

The book is about an artistic movement that, in the space of a couple of decades, developed extraordinary momentum as an occasion and catalyst for public debate in Cuban society, and which—with equal rapidity, not to mention paradox—became a poster child for political commitment in the global art market.

The book traces these developments, looking closely at the works and the circumstances under which they were produced. I also zoom out into the broader context, looking at the ways that Cuban state policies impacted cultural production on the island and its circulation internationally: this includes sections on how this “new Cuban art” was neutralized into a mere formal innovation by the national museum, alongside the parallel martyrological narrative that plays out in the Museum of the Revolution.

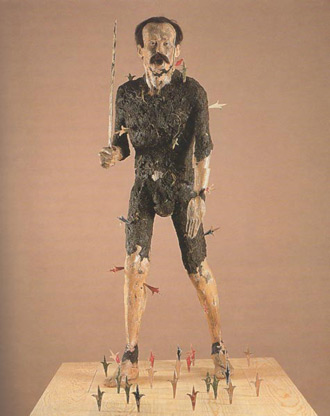

Juan Francisco Elso’s “Por América” is one of the many remarkable works that I write about. An effigy of José Martí, it is an exquisitely painful portrait, depicting the Cuban national hero as a barefoot figure clad in mud and wielding a machete.

Elso’s Martí achieves, through formal means best recognizable in the folk carvings of popular heroes, some amplifications to and reopenings of the meaning of Martí whose essence, as that of all the heroes, had become fixed and frozen a long time before. It escaped monumental history’s discouragement (we can never measure up), antiquarianism’s first principle of remove, and acknowledged that in fact it was living with a very tenacious, unrequited past.

Elso’s Martí made plain the doubled relation that he and others had to their own social space: with the ambivalence of both insider and outsider positions they were part of it, identified with it, plugged into its energy source, but unsatisfied by it and profoundly critical of it. In its act of historical memory, the work had rescued remembering from rote distraction in the name of reconstituting a sense of personal, everyday ethics. It collapsed the vertical gap of deity and reclaimed the revolutionary promise of everyday heroism. Its doubling made the hero, and the “terrible desire to believe” uncanny, potent, unnerving and poignantly awry.

In fact Elso’s portrayal was so far removed from the version that is ubiquitously present across the island—from monuments to patios—that it was denied the prize that an international jury wanted to award it at the Havana Biennial in 1986.

The controversy was about the de-heroization of an icon. Paramythological and parahistorical, icons are symbols intended to be clear in their meaning. Elso took Cuba’s central icon and made it so complex, contradictory, emotional, and ambiguous that it was impossible to nail down. No, it said, it can never be clear. Martí’s death had set the standard for proportions of sacrifice in Cuba, and Elso’s Martí died incomplete and unresolved, his entire project reopened as a wound in the work, an open wound at the heart of the contemporaneous Revolution.

“Paramythological and parahistorical, icons are symbols intended to be clear in their meaning. Elso took Cuba’s central icon and made it so complex, contradictory, emotional, and ambiguous that it was impossible to nail down.”

The “new Cuban art” was notable not only for the nature of its objects, actions, and debates, but also for the energies that it collected around itself.

The linkage of art to revolutionary politics is a key aspect of Latin American modernity. One of the singular accomplishments of the new Cuban art has been its capacity to generate mobility around not only the explicitly political situation, but also the quotidian realities of Cuban society.

On the one hand, this history speaks forcefully to the fundamental question of art and artists’ agency; on the other it provides some tentative answers to the existential challenges of disenchantment. What happened in Cuba gives us an acute sense of what it can mean, both for individuals and for societies, when we engage in that most contemporary of dilemmas—heading both to and from utopia.

The movement was an extraordinary phenomenon, erupting in the midst of a claustrophobic and oppressive cultural climate. The 1970s, a period known as the “grey” years, was the proximate referent for the movement, with its sovietization of culture and consolidation of political power and control.

But the new Cuban art was also, crucially, the dynamic entry of a group of young people, born around the time of the Revolution and formed not only by its encroaching orthodoxies but also by its poetic idealism and dedication to independence.

Hailed in its earliest moments for its “sense of joy and human affirmation” and its “acceleration of imaginative reach,” the new Cuban art almost completely redefined the possibilities for a work of art on the island. Emotionally, as the critic Gerardo Mosquera commented at the time, “the response [was] a sensation of possibility.”

The 1990s brought a near-total collapse of the nation’s viability, both economic and psychic: precipitous drops in food and basic goods, transportation, electricity, hope.

As a result of a complicated combination of factors (ideological challenge of the work and ideological crisis of Cuban and European socialism, economic opportunity afforded by art commerce and economic crisis of the nation, emigration of most of the “problematic” artists, maturation of others amid an effective erasure of the past, intense challenge and struggle at every juncture on the quotidian level, preoccupation with immediate and individual survival, exhaustion, disillusionment, cynicism, opportunism, and anger, to name some of the most important), artists once again voiced the complicated realities of the nation, trading the fiery, utopian energies of the “Generation of the 80s” for the darker question that had become central: How, after building the sky, does a people learn to live with disenchantment?

The artists were all born after the Revolution of 1959, and were authentic products of it. They insisted on an art that was free from ideological coercion, expressive of the complex cultural heritages of the island, and connected to contemporary practice elsewhere in the world. Above all, they insisted on an art that was truly revolutionary, in its ethical foundation and independence of thought.

Their work became a root space of struggle and humor, an aggressive, caustic, bulls-eye art. As it accelerated into a critical movement, the work spilled out of studios, classrooms and galleries into the streets, magnetizing a large and diverse following by raising the taboo subjects of corruption, dogmatism, cult of personality, lack of democracy, and so on.

In the space of just a few years, visual art became the primary interlocutor of Cuban society, surely one of the most vertiginous intervals in the history of art anywhere.

Rachel Weiss has curated exhibitions and written books including “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin 1950s-1980s,” Making Art Global: The Third Havana Biennial 1989 (forthcoming from Afterall Books), and To and from Utopia in the New Cuban Art, featured in her Rorotoko interview. She is currently working on a series of essays about artworks that either do or else try to cross ethical boundaries and put their viewers into questionable situations. Weiss teaches in the Art History and Arts Administration and Policy departments at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.