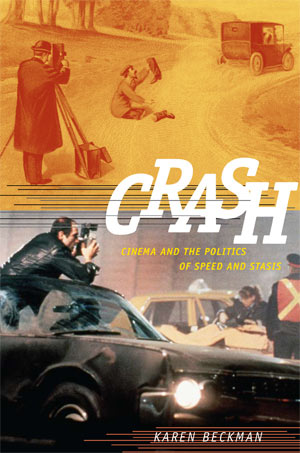

Crash explores the role of the car crash in film history and contemporary art practice.

I begin by recognizing that the histories of cinema and the automobile, born at the same moment, are inextricably intertwined—but resist the assumption that the shared history of cars and films necessarily means that cinema is always resonant with concepts like speed, motion, flight, and progress.

You might think of this as an “anti-road movie” book. While in the Road Movie, as in mainstream action cinema, car crashes and other spectacles of technological disaster generally offer a moment of pause in which the narrative can either regain its momentum or take another direction, in the films I focus on, the moments of breakdown, technological failure, and the rupture of discreet bodies constitute the primary focus. I am interested in guiding attention towards these moments of narrative and visual stasis, and in examining how cinema presents itself when the camera is aligned not with the sweeping horizontal motion of a lone car moving through iconic American landscapes but rather with the modes of vision, relationality and experience that the car crash produces.

The book travels across the twentieth century, noting the persistence of this figure not only for filmmakers, but also for writers and artists trying to define their own practice through an engagement with this disaster-inflected view of what cinema is.

I begin by looking at a number of very short films made at the turn of the century by cinema’s earliest pioneers, including Cecil Hepworth and Walter R. Booth, all of which explore the new medium’s limits and possibilities through the parallel limits and possibilities of emerging automobile technology.

As I continue to pursue this relationship through silent slapstick comedies of Harold Lloyd and Laurel and Hardy, industrial safety films and car crash test films, it becomes clear that the cinematic car crash opens ways of thinking about not only what cinema is or could be, but also about how technology’s breakdowns create tears in the illusory fabric of social progress. These tears can function critically, allowing different ways of both looking at the world and using audiovisual technologies to reflect on those viewing habits.

The last four chapters of the book all explore this intertwining of social critique and aesthetic experimentation through close readings of works by Andy Warhol, Jean-Luc Godard, Ant Farm, J.G. Ballard, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Nancy Davenport.

“I wanted to capture the essential and radical hybridity of both the medium of film and of Cinema Studies. As Cinema Studies becomes more of a ‘discipline’ in its own right, I think we have to be careful not to throw the bastard out with the bathwater.”

This book grew out of a number of different and at times very intense interactions, conversations and collaborative projects. Sometimes the conversations were in person, and in other instances they involved repeated reviewings of films, as well as rereadings and rethinkings of theoretical texts and arguments.

Many years ago, I was fortunate enough to have the chance to teach a course on contemporary literature as an assistant to the poet and scholar Craig Dworkin, from whom I learned an incredible amount. J.G. Ballard’s novel Crash was one of the assigned texts, and that’s really where I began thinking about car crashes specifically. Through conversations with Craig, and through listening to his lectures, I began to think about how one moves between theoretical discourses like feminist and queer theory and formally experimental work that comes out of the avant-garde traditions, work that often takes women as sites rather than agents of experimentation.

I was also reading Susan Suleiman’s work at the time. Both types of work appealed to me, but they often seemed incompatible, and this moment marked a type of “crash” or collision in my own intellectual formation. It was an extremely generative time, and I’m very grateful to Craig for his generosity.

Around the same time, the art historian Branden W. Joseph was co-organizing a conference on Pop art, architecture and literature of the 1960s, and he invited me to present a paper on literary pop. The book’s chapter on Ballard’s Crash grows out of that conference, and it was really because of that particular context that the whole project became one involving the issue of intermediality, and how experiences, experiments or concepts transform as they are translated from one medium into another.

This conference was also formative for the project because it included a screening of Andy Warhol’s film Since (1966), a reenactment of the Kennedy assassination shot in Warhol’s factory and using his couch as a stand in for Kennedy’s Lincoln convertible. The film was introduced by the late Callie Angell, who, from that moment on, gave incredibly helpful advice and suggestions for the book—not just for the Warhol chapter, but also for the larger project of understanding how this trope has functioned in diverse ways throughout the history of film.

By this point, I was teaching at the University of Rochester, and my own methodological approach was developing in part through conversations with Douglas Crimp about queer theory on the one hand, and with Sharon Willis about feminist film theory on the other. Once I moved to the University of Pennsylvania, the book continued to be shaped by my experience of teaching in both the Program of Cinema Studies and the History of Art department. More than anything else I’ve written, this book strikes me as, among other things, a history of intellectual engagements and friendships, and I like that aspect of it.

I am coming to think that most of what I’ve written concerns interstitial spaces, whether between visibility and invisibility, life and death, cinema and photography, stasis and motion, feminist and queer theory, cinema studies and art history. My current research explores the relationship between documentary and animation film, and so also fits this interest in a border space. At the same time, throughout my time working with the MIT journal Grey Room, my co-editors and I have tried to foreground work that demonstrates strong intra-disciplinarity, and I tend to like work that both recognizes and crosses boundaries.

There is an undercurrent in Crash, as there is in a book I co-edited with Jean Ma, Still Moving, that is interested in the institutional future of the study of moving images—where it will find a home, what it should involve, and how, in collaboration with our students, we can forge the best possible spaces for critically engaging cinema’s past, present and future.

Originally, in fact almost up to the point of publication, the book was called “Little Bastard”: Car Crashes, Cinema, and the Politics of Speed and Stasis. With this title, which took its inspiration from the Porsche 550 Spyder in which James Dean died, I wanted to capture the essential and radical hybridity of both the medium of film and of Cinema Studies. As Cinema Studies becomes more of a “discipline” in its own right, I think we have to be careful not to throw the bastard out with the bathwater.

I hope you read the introduction first, as this would clarify my own stake in car crash films. I am constantly surprised that I have written a book on cinematic car crashes—but this element of surprise is what I love about the act of writing.

Here the reader will also find my engagement with Vivian Sobchack’s important work on film phenomenology and the corporeal rather than psychic dimension of the film experience. Though there are plenty of comic cinematic car crashes, and I write about those, watching a crash onscreen can be a visceral and even traumatic experience. But it is never the same as being in real crash, or even watching a real crash occur in front of your eyes.

Sobchack wrote a very passionate essay criticizing Jean Baudrillard’s reception of Ballard’s Crash. In it, she lambasted Baudrillard for his neglect of the real, physical body’s pain. Furthermore, she wrote this essay in the wake of having had her leg amputated, a fact that, for me, brought the the ethical issues surrounding the cinematic representation of historical and fictional suffering bodies into sharper focus in a very challenging way.

Chapter Three would also be a good place to start. It looks at how film and photography were used in car safety research as well as how industrial films made by American car companies visually engaged the contradictory fantasies that the automobile seems to provoke. On the one hand, the automobile offers a private interior and safe space akin to a home, except that it allows the driver to be alone in a way that the family home does not. On the other hand, the automobile represents an anonymous, high-speed, and transparent new technology aligned with the psyche’s desire for risk, exhibitionism, transgressive sociality, and speed. Commercially driven, the industrial films of the mid-century emerge at the nexus of this double desire for risky speed and guaranteed safety.

Although Paul Virilio has made important critiques of the way ordinary technologies of transportation and vision participate in the militarization of everyday life, my book argues that his work tends to oversimplify the nature of risk and the capacity of cinema. For me, Virilio’s view of both cinema and the automobile is too singular, too totalizing, and also too ahistorical. My approach involves selecting specific examples that offer alternatives to Virilio’s understanding of the interactions among the car, the accident, and cinema. Although examples of the collusion between visual technology and the military proliferate daily, making Virilio’s critique necessary, I wanted to produce a work that would add another voice to this conversation, one that wasn’t ready to just give up on cinema.

Another distinction between my approach to the accident and Virilio’s is that we have different relationships with the concept of “responsibility.” My own is informed by the work of Leo Bersani, Douglas Crimp, and Tim Dean on sexuality and desire; by Jean Laplanche’s theory of the drives; and by Judith Butler’s Giving An Account of Oneself, in which, influenced by Levinas, she asks what it means to behave ethically when we know that we can never fully know the self, and therefore can never fully control what it does. I am interested in exploring what comes out of this movement between psychoanalysis’s focus on the subject and the unconscious, and a focus on social and political structures. Virilio is constantly frustrated with the blindness, violence, and stupidity of human behavior; I am interested in where we go after that.

“On the one hand, the automobile offers a private interior and safe space akin to a home, except that it allows the driver to be alone in a way that the family home does not. On the other hand, the automobile represents an anonymous, high-speed, and transparent new technology aligned with the psyche’s desire for risk, exhibitionism, transgressive sociality, and speed.”

I think the book resonates strongly with contemporary anxieties about “homeland security” as well as environmental and financial disasters.

In fact, before I began working on Crash, I had planned to write a book on how and when the feminist movement appropriated a language of violence and terrorism. That was before 9/11. I did write a couple of essays after the attack on the twin towers within the frame I had earlier imagined (see here and here). But “terrorism” was no longer the best frame to address the kinds of questions I wanted to think about.

“Terrorism” had become too specifically tied to the contemporary landscape, and this overshadowed the history of the feminism movement’s relationship to violent discourses and forms of action. Crash emerged as the new project, though I can still see traces of the earlier project in the book’s preoccupation with risk, ambivalence, and the question of “movement,” its dangers and its possibilities.

Karen Beckman is the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Professor of Cinema and Modern Media in the department of the History of Art and the Program in Cinema Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. She is also a senior editor of Grey Room. Besides Crash, featured in her Rorotoko interview, Karen Beckman is the author of Vanishing Women: Magic, Film and Feminism (Duke, 2003) and co-editor of Still Moving: Between Cinema and Photography, (with Jean Ma, Duke, 2008), and Picture This! Writing with Photography (with Liliane Weissberg, Minnesota, forthcoming).