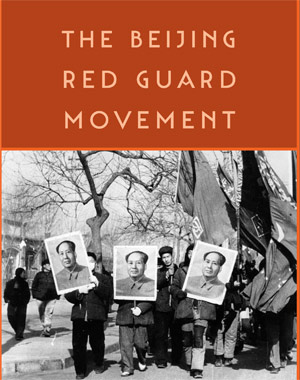

It seems that almost everyone has heard of Chairman Mao and China’s Cultural Revolution and the “red guards” of the late 1960s. The “red guards” were students who rampaged through schools and government offices, terrorizing officials and intellectuals, humiliating them, beating them, and even killing them. These events are seen in China as a national catastrophe, so traumatic that even today publication on the period is almost completely forbidden in China.

Remarkably, there is no book in any language that describes in detail the activities of these students in the Chinese capital. But the Beijing red guards set the trend for the movement nationwide, and many of them became national celebrities. By trying to explain how and why students became involved in all of this, and chronicling what they did, my book is intended to fill a huge gap.

The greatest puzzle about the red guards is that they fought one another almost as violently as they persecuted intellectuals and government officials. The question is, why?

For more than two decades academics have claimed that students divided into two different groups depending on how much they benefited from the status quo. “Conservative” red guards benefited from the system, were close to the leaders, and defended them. They attacked the weak and defenseless—intellectuals, old members of “capitalist” classes. “Radical” students had build-up resentments against the status quo and wanted to change things. They attacked the powerful—communist officials, party members. In other words, according to this view, the students fought one another because some sought to change an oppressive system, while others tried to defend it.

In Fractured Rebellion I explain that this view turns out to be wrong.

I am, in fact, the first person to look closely at the many materials on the red guards that have become available in the past ten years or so. I have looked closely at the backgrounds of student leaders and read their extensive writings at the time of these events. Somewhat as a surprise to me, and I suspect to many others who thought they understood these events, it is now clear that students on both sides of the struggle were from the same background. The leaders on both sides were close to their school’s party organizations, came from politically reliable families and already held student leadership posts in their schools.

So why did they join groups that fought with one another for almost two years? The best short answer is that student leaders were searching for clues about how to respond in a situation where a very coercive political system was breaking down.

But this is a fairly complex story. Students were forced to make choices in confusing and rapidly changing circumstances. They made different choices, and took different stands, and this ended up dividing classmates and friends, even family members, against one another. The Chinese system at the time also punished people severely for making political errors; if you ended up a loser, your future would be ruined, at best, and you might be imprisoned or sent to a labor camp, at worst. Once you took a stand and confronted others, you paid a very heavy price if you lost. So student red guards, in a sense, were trapped into a struggle in which the prospect of losing was unthinkable.

They fought on against one another, with increasing violence, for almost two years. In the end Mao, disgusted with his darling student radicals, sent in the army to suppress them, and sent almost all of them to rural farms for a decade. Fractured Rebellion tells the whole two-year story.

“So why did they join groups that fought with one another for almost two years? The best short answer is that student leaders were searching for clues about how to respond in a situation where a very coercive political system was breaking down.”

I’m challenging a way of thinking about politics common in fields like sociology and political science—the one in which people have interests based on their jobs, their levels of education, their political affiliations, and their future prospects. When political circumstances change, giving them opportunities to advance themselves, raise grievances, or force them to defend what they have, they will band together to advance or defend their interests with others who are similar to them.

This is exactly what past accounts of China’s red guards have claimed. In this view, students chose sides based on who their parents were, whether they were already student leaders or party members, because the Cultural Revolution gave them the opportunity to express these interests for the first time. So in this view the students fought against one another, spinning out of control, because they had fundamentally different social positions and different interests.

I used to believe this, and wrote a good deal about China’s Cultural Revolution in this vein. But when I started to read carefully the many accounts written by students in Beijing at the time these events took place, I realized that the facts just didn’t fit.

Students who led both sides of the struggle came from the same backgrounds. They were divided into antagonistic groups because they became drawn into divisions among China’s leaders, each side thinking that they were doing what Mao Zedong wanted and expected, but not realizing, at first, that they were in fact being drawn into a leadership conflict. In the book, I try to spell out as clearly as I can how this complex process played out.

People’s choices in confusing historical circumstances aren’t as clear as social scientists sometimes think.

The red guards’ violence against their victims was shocking, and this is how they are rightly remembered. It turns out, however, that they were not all mindlessly violent. In fact, a very vocal group of students from China’s best high schools spoke out strongly and repeatedly against the “gangster-ish” behavior of the movement in the summer of 1966. They argued for more restrained and disciplined behavior, and certain Communist leaders who were trying to steer the students onto a less violent path gave them a lot of support.

The problem with this is that Mao himself saw complaints about violence as unnecessarily restricting “the masses.” He wanted things to get more chaotic.

But the students who opposed violence wouldn’t give up, and eventually challenged the radical officials under Mao who were urging the students forward. They ended up being persecuted by their red guard opponents who enthusiastically called for “dictatorship” over these “class enemies”—who were then arrested and imprisoned.

It was only as detailed reports of the mounting death toll in the capital reached Mao—red guards murdered more than a thousand people during the first month—that he told his subordinates to stop making such a fuss.

What is most galling is that those very students who protested violence were then blamed for all the violence of the red guard movement up to that point in time.

This is all described in Chapter 5, which shows how utterly cynical and nasty the politics of the period could be, and how confusing and dangerous it could be for students, especially red guards who were relatively well-meaning.

In working on the Kyoto Protocol negotiations, I often encountered the view that, if the Protocol’s compliance committee cannot impose “binding” sanctions on violators, then this means that the Protocol itself is not legally binding. Such a view is certainly understandable. How can a norm be legally binding if the legal consequences for its violation aren’t binding? Isn’t this like saying that stealing is illegal, but the jail sentences imposed against violators are optional?

To try to make sense of these puzzles, I explore the nature of international norms and their relation to behavior. I then analyze what it means to characterize a norm as “legal” or “binding” and examine other important dimensions along which international environmental norms vary.

“People’s choices in confusing historical circumstances aren’t as clear as social scientists sometimes think.”

The Cultural Revolution was certainly a crucial turning point in China—and a defining event in 20th century history. We really know very little that is well-grounded about this complex period, and much of what we think we know is either a caricature of actual history or just plain wrong.

In fact, as I researched for this book, I realized how poorly I understood China’s Cultural Revolution, even though I have been reading and writing about it for some years.

Research and publication on the Cultural Revolution is suppressed in China; for the time being, most of this work will have to be carried on outside.

So my book will not be the last word on the subject. But I hope it will convince others to look carefully at the materials that are now available.

Andrew Walder is currently the Denise O’Leary and Kent Thiry Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University. He previously taught at Columbia University, Harvard University, and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. He began studying Chinese politics as a student in the early 1970s, and has long specialized in research on Mao-era China, focusing on social transformation and political conflict after Mao. He is now writing a comprehensive social and political history of the Mao period.