Relationscapes attempts to develop a theory of the incipiency of movement. Initially, my main concern was to continue a line of questioning developed in my previous book, Politics of Touch, which already aimed to explore the amodality of sensation and how sensation is always linked to movement.

The focus of Politics of Touch was on the sensing body in movement’s relation to the political; emphasis being on how the sensing body in movement is distinct from the ubiquitous concept of the body-politic. Upon finishing Politics of Touch, I wanted to delve deeper into the microperceptual fissures opened up by my work on touch/sensation. This allowed me to engage more thoroughly within dance and movement studies (which have tended to focus on semiotic inquiry or movement in its phase of displacement) as well as on artistic and protopolitical practices that focus on movement.

A key concept in Relationscapes is preacceleration. I developed this concept to get to the idea of a movement in its very primary phases of initiation, before it actualizes as such. Preacceleration allows us to begin to develop a modality of thought for the virtual intensity of movement in its incipiency. To explore movement in its incipiency allows for a different stance as regards movement. It enables a focus on potential by exploring in detail the micromovements (including rhythm and duration) that are alive at the phase where a particular shape has not yet taken hold. Once the movement is actualized (once a step is taken, for instance), movement is reduced to very specific conditions and is acted upon by its co-constitutive surroundings (including gravity).

Taking the thought of preacceleration across various fields, Relationscapes aims to develop a transversal vocabulary for how movement functions in areas as different as Leni Riefenstahl’s films, Étienne-Jules Marey’s’s chronophotographs, Dorothy Napangardi’s paintings, Shusaka Arakawa and Madeline Gins’s architectural concepts, and William Forsythe’s choreography. The book crosses these fields (and more) with a continuous concern for the development of a politics of touch—a sustained engagement with the sensing body in movement.

Relationscapes draws to a close with an emphasis on language. Recent work by so-called low-functioning (non-speaking) autists suggests that language plays a large part in the thought of how movement moves. With Amanda Baggs’s extraordinary short video, In My Language, I attempt to open the way for a reading of preacceleration (here called prearticulation) that allows for an engagement with the affective relational milieu a protolanguage (of gesture and sensation) calls forth. Language in Baggs’s work is not conveyed solely through words, but through the creation of a responsive environment that facilitates complex communication beyond the limited notion of language-as-spoken.

Relationscapes seeks to make a philosophical contribution to art practices of various kinds, taking seriously the notion that an art practice—be it painting, dancing, filmmaking—develops concepts in germ and activates them in the language of its technicity. Rather than speaking “about” art, from the outside of its incipient movement, Relationscapes aims to intercept concepts in the making, activating various modes of articulation in tandem with their emergence as artworks in their own right. This is not a book that explains movement or stands outside a practice to articulate it. It is a book that attempts to dance in the writing, looking for a way to articulate what is perhaps most ineffable about art: how it moves us.

“A key concept in Relationscapes is preacceleration. I developed this concept to get to the idea of a movement in its very primary phases of initiation, before it actualizes as such.”

Relationscapes is a very Whiteheadian book. From the outset, it philosophically attempts to lay out a process philosophy and to outline how Alfred North Whitehead’s thought is in conversation with the work of Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, Henri Bergson, Gilbert Simondon, William James, and Brian Massumi, to name a few.

Whitehead’s process philosophy is focused around the idea of the actual occasion. For Whitehead, while process is what constitutes the extended continuum of the world, a certain monadicity is absolutely necessary. The emergence/prehension of actual occasions is synonymous with what we know/experience. There is no actual experience outside of an occasion’s coming into appearance, and “we” are not prior to them. Occasions are co-constituted with their worlding, creating superjects (subjects of the event) in their passing. A radically reconstituted engagement with subject/object relations, Whitehead’s approach offers an opening for a microperceptual analysis such as that undertaken in Relationscapes.

The first arena of emphasis Relationscapes thinks through is dance, specifically relational movement. I conceptualize relational movement (which is a continuation of the movement exploration foregrounded in Politics of Touch, which circled around Argentine tango) as the very modality of movement: movement always moves relationally. This takes into account Bergson’s idea that duration (movement-moving) is extracted (as displacement) when measured as such. Movement is thus not what is added to time but what is subtracted from duration. If all movement is already relational (creates spacetimes of experience even as it composes with them), movement-moving can no longer as easily be sidestepped (as it has often been in dance and in cinema in lieu of a focus on a movement-grammar, a narrative structure, etc.). To engage with movement-moving is also to create a more complex vocabulary around choreography and improvisation (where both can function as subtractions of movement-moving).

Relationscapes then continues its movement exploration within the realm of Encephalitis Lethargica, a medical condition associated with Parkinson’s’ disease where the activation of movement is inhibited. The focus throughout this chapter and in the subsequent three chapters/interlude—on Marey’s chronophotographs, Norman McLaren’s animations, and the contemporary field of dance and technology—is on forms of activation as they relate to incipient animation (be it in terms of Oliver Sacks’s patients, motion detection software, or the editing process in cinema) to highlight how these divergent practices make use of the microperceptible edge of movement-moving.

The book takes a turn toward the political in the last chapters, proposing first that we take a closer look at the movement practices foregrounded in Leni Riefenstahl’s films. Contrary to much work on Riefenstahl’s filmmaking, these are not images of solitary bodies: they are uncanny composites of movement-moving. No matter where you cut them, not only do they continue to move, but they continue to operate serially, both within and across the frame (each image is always more-than the image of a single body). This has implications as regards the so-called fascist aesthetic and the notion of transcendence.

The following chapters look at the politics and aesthetics of contemporary Aboriginal painting in Australia. This section perhaps most forcefully draws together how a focus on movement is also an invitation to rethink ethics/politics. Examining in detail the ways in which Aboriginal people in the Australian central desert build their politics out of a durational notion of movement, and then paint this movement in a recasting of the interplay between the abstract and the representational, these chapters suggest new ways of thinking art in relation to a moving landscape and a spiritual realm that moves-with life in the making.

This is pursued in the final interlude, which explores the work of Arakawa and Gins. The last chapter turns its attention to language, exploring the politics of representation in theories of language and literacy that effectively shut down the potential of language with respect to affect and the sensing body in movement. Focusing on the autistic activist Amanda Baggs’s film In My Language, I suggest that we have a lot to learn through modalities of thought and communication proposed by Baggs. Imbricating spacetimes of experience with communication (foregrounding the complex sensory dimension of the world conceived as relational environment), Amanda Baggs complicates the notion that language functions only denotatively and proposes instead a challenging and important interweaving of the sensing body in movement and language in the making.

As a dancer, an artist and a philosopher, these concerns are very close to home for me. I strongly believe that different practices hone different vocabularies and articulate themselves according to the technicities the practices foreground.

When language opens itself up to more-than semantic articulation, a wide array of potential is unleashed that provokes a more complex aesthetic and political field of engagement. Working transversally across practices allows for this complexity to begin to come to light, repositioning the role of the academic/philosopher in relation to art. To delve into the experiential microperceptual realm allows for a dancing-with, a painting-with that promises no pre-constituted ethics but allows, perhaps, for a different kind of conversation to begin. The politics of this conversing seem to me to allow for a more sustained engagement with difference at the very incipient level from which movement moves us. It is here that the creative germ is most powerful, and with it, the potential to activate the incipient links between creative practice and micropolitics.

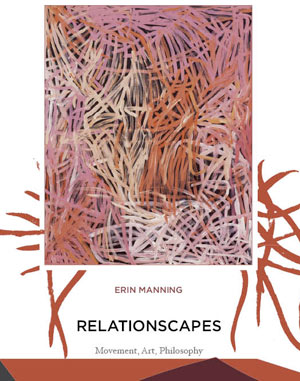

A reader encountering Relationscapes in a bookstore might find themselves attracted to the front cover, which is a reproduction of a painting by Australian Aboriginal artist Emily Kngwarreye. This might lead her to open the book to the chapter on mapping as it functions in Aboriginal culture. In this chapter, I take a close look at the work of both Clifford Possum and Emily Kngwarreye, two contemporary Aboriginal artists.

To paint the landscape with acrylics is a relatively new form of art for the Aborigines of Australia. Until the early 1970s, stories of land and spirit were evoked mostly through other media—sand, bark, wood. The paintings produced since then are all associated with Dreamings—Jukurrpa—which are an integral aspect of life in Central Desert society. Stories told for more than 50,000 years of continuous history, Dreamings not only speak about the landscape and its vicissitudes, they create spacetimes of experience.

For Aborigines, life is Dreaming in the sense that the coordinates of spacetime out of which everyday lives emerge are significantly in line with creation and recreation of the land and its laws (which is one of the translations of Dreaming). The land is not an extension of the Aborigines—it is them. To be the land is to become in relation to it, in relation not to space itself, but to the living coordinates of a topological relationscape that embodies as much the law as it does the grains of sand that prolong it in real-time.

Clifford Possum is significant both in the history of contemporary Aboriginal art and in terms of what Relationscapes attempts to convey. One of the foci of this chapter is Possum’s so-called “map series.” In this series, Possum paints the Dreamings for which he is custodian (Dreamings are managed through complex kinship ties), completing a number of paintings that “map” the large areas and stories the Dreamings conjure. In terms of movement-moving, it is perhaps most noteworthy in these paintings that Clifford Possum does not adhere to a Euclidean set of coordinates for his map. He paints them while moving around the canvas lying on the ground. This results in a continuously shifting perspective that might astound those of us who organize landscapes into grids. In Aboriginal culture, the landscape—and the Dreamings that activate it—are always experiential. The landscape is never observed from outside its eventness, nor is it painted as though it had stopped moving.

“Imbricating spacetimes of experience with communication (foregrounding the complex sensory dimension of the world conceived as relational environment), Amanda Baggs complicates the notion that language functions only denotatively and proposes instead a challenging and important interweaving of the sensing body in movement and language in the making.”

In my work, Relationscapes has opened the way for the continued exploration of the relationship between microperception and micropolitics. It has also introduced me to a growing group of philosophers, artists, dancers, activists whose concerns—both aesthetic and political—are in tune with the propositions Relationscapes calls forth.

This has fed my work as director of the SenseLab, which, with a large array of international and local collaborators, organized an event in 2009 called Society for Molecules, and is planning a next event for July 2011, Generating the Impossible. At SenseLab, I seek to allow for a wide regrouping of collectives and individuals who similarly are impatient to create modalities of existence and thought that propose more creative ways of working academically and in the art world.

Erin Manning holds a University Research Chair in Relational Art and Philosophy in the Faculty of Fine Arts at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. She is also the director of SenseLab, a laboratory that explores the intersections between art practice and philosophy through the matrix of the sensing body in movement. In her art practice she works between painting, fabric and sculpture. Besides Relationscapes, featured in her Rorotoko book interview, Manning is the author of Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty (University of Minnesota Press, 2007) and Ephemeral Territories: Representing Nation, Home and Identity in Canada (University of Minnesota Press, 2003).