Italy in Early American Cinema traces the formal and ideological history of an aesthetic tradition, the Picturesque, from its original association with Italian landscapes to its deployment in early American cinema’s representation of the country’s distinct geographic and racial diversity. Thus the book touches upon formal conventions about national and racial difference that preceded the inception of moving pictures and even of photography, conventions which both producers and spectators, no matter their social or national background, knew and appreciated.

This work began from the consideration that all too many studies of race in early American cinema tend to focus rather exclusively on individual groups. Reacting to this parcelization, I call attention to a sustained, transatlantic connection between how early American cinema as a whole represented racial difference and national identity and how, on both sides of the Atlantic, literature and image-making media had for centuries popularized romantic and entertaining representations of distant landscapes and populations.

This pervasive aesthetic tradition, known as Picturesque, referred to both actual and painterly landscapes whose accidental or studied appearance turned their irregularity and roughness into appealing aesthetic effects. The Picturesque had emerged in conjunction with how European travelers, including writers and artists, romanticized Southern Italy’s ruin-dotted city views, pristine forests, erupting volcanoes, and quaint populations. Over time, the Picturesque’s reconciling arrangements came to imbue not only burgeoning tourist and image-making industries promoting the pleasing representation of distant places and populations, but also modern nations’ idealized representations of their own striking natural views and marginal dwellers.

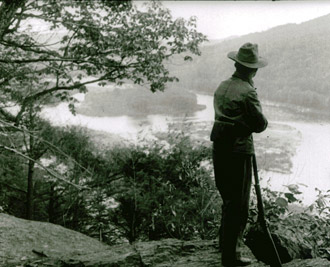

After showing the international popularity of Italian picturesque representations, I discuss how the Picturesque became the first American aesthetic. In the United States, the Picturesque popularized charming depictions of natural and urban sceneries, from the Hudson River Valley and the Wild West to the nation’s largest metropolis, New York City. Through pleasant arrangements of landscapes and man-made presences, the Picturesque offered something that American tourist and railway boosters as well as artists, writers, and filmmakers deeply needed: a familiar design to sort through, exoticize, and thus domesticate the wilderness of American natural and social landscapes—from the Niagara Falls and the immense Western forests to the Lower East Side.

Early American cinema was keenly sensitive to the Picturesque. Western, gangster, and melodramatic films, as well as travelogues, deployed the picturesque tradition of “agreeable pictures” to idealize—to Americanize, that is—“agreeable races,” from noble, yet vanishing Native Americans to Italians, the Picturesque’s original subjects. Ultimately, however, the Picturesque identified a pleasing, manageable, and assimilable alterity that was not for everybody: to be picturesque or “colorful” implied not to be “colored.”

“Western, gangster, and melodramatic films deployed the picturesque tradition of ‘agreeable pictures’ to idealize—to Americanize, that is—’agreeable races.’”

If the argument I make is fairly simple—even intuitive: like other media, cinema domesticated the alleged wilderness of remote places and populations into entertaining representations—executing it required familiarity with a transatlantic network of visual practices and critical debates.

Thus the book incorporates illustrations and methods from the history of painting, print-making, photography, landscape architecture, anthropology, tourism, theatre, caricature, and moving pictures. This wide framework of references allowed me to show how the power-laden aesthetics of the Picturesque crossed historical periods and geographic distances, moved from the canvas to the photographic plate and the movie screen, and, consequently, served as a long-lasting resource for both racial allegations and identity formations.

The project grew in such a way because of personal interests and inclinations: my background in philosophy helped me think through larger aesthetic debates. But this broad approach was time consuming. Ultimately, I was able to carry out the project because of fortunate academic opportunities. A three-year postdoc at the University of Michigan’s Society of Fellows enabled me to read extensively and entertain an intense dialogue with junior and senior scholars from other fields, without the customary obligations of regular teaching and service. A few years later I was able to have the same experience during a one-year fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies at Harvard, where I rewrote the manuscript while trying to weave together all the different strands of my research. Under these privileging circumstances, the original project, initially centered on the relationship between early cinema and Italian immigrants in New York, gained in scope and ambition.

The broader implications of the argument put forward in the book are, I think, twofold. On the one hand, if we take seriously the intermedial history of films’ representations, we ought to revisit the widely-held notion of moving pictures’ radical novelty and distinctive modernity. My study seeks to show that, at least from a racial viewpoint, films’ communicative power was actually fraught with debts to powerful, older, yet equally modern, geoaesthetic traditions.

All too often, the argument about cinema’s novel aesthetic property has stressed its unique capacity to reproduce movement, namely the photographic embalming and manipulation of time. In this study I seek to complement this assessment by showing moving pictures’ creative complicity with popular notions of spatial and geographic distance, and related perceptions of social and racial diversity. By relying on, and furthering, this long-lasting aesthetic tradition, familiar to both image-makers and consumers, cinema readily achieved a broad appeal even among the subjects of films’ racially-charged depictions. This is the second implication of my study.

In the past, scholars have argued that immigrants’ exposure to moving pictures offered them a radically new experience, one that could not easily be assimilated with their own cultural universe, and that in the process “Americanized” them. My research on the international pervasiveness of Southern Italian landscapes of erupting volcanoes, charming seashores and colorful banditi suggests otherwise.

Since before coming to the United States, Italian immigrants were strikingly familiar with these conventions, which pervaded Sicilian stage plays, Neapolitan melodramas, and local films productions. Not only did they recognize picturesque representation on American screens, but they also contributed to the resilience of picturesque conventions in their own remarkable theatrical and filmmaking enterprises—as archival holdings and the ethnic press reveal.

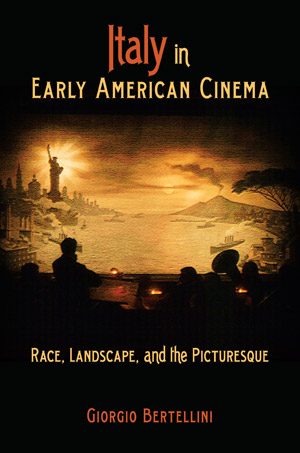

The book cover’s composite landscape view is suggestively meant to capture the multiple layers of the Picturesque’s transatlantic circulation. Featured as a stage backdrop in the 1917 footage of The Godfather: Part II (1974) and, originally, in the logo of the music-publishing firm of Coppola’s grandfather, the image links the picturesque representations of Naples and New York in a single, impossible view. Here, Old and New World are reunited in a common exoticizing gesture that not only reproduces immigrants’ nostalgia and wonder, but also shows how the Picturesque, despite its long and patrician history, was in 1910s America a widely appreciated visual currency exchanged across social and cultural barriers.

If someone were to flip casually through the pages of the book, I would hope that they would appreciate, and be intrigued by, its variety of illustrations.

Of course I do not expect these images to convey per se the trajectory of my argument. Yet, even when starting from the end—that’s how I flip through books, anyway—my hope is that the casual reader would formulate hypotheses about what could possibly link film frames from immigrant melodramas, Griffith’s Civil War film In The Border States (1910), and such travelogues as Picturesque Colorado (1910), with popular prints from Harper’s Weekly (1875) or the bestselling volumes of Picturesque America (1874), old photographs by Riis, Stieglitz, Watkins, Hine, von Gloeden, and Sommer, and even older paintings by Cole, Gilpin, Volaire, Rosa, and Lorrain.

I would hope that the book’s front and back covers, not to mention its rich filmography, could similarly prompt the reader to want to read (or just flip through the pages) more.

“A historiographical consideration of larger geopolitical occurrences reveals films’ expressive, ideological, and commercial debts to a host of other representational practices.”

Italy in Early American Cinema seeks to place the question of race at the center of our discussions on how early American cinema became a national, mass entertainment. One of the goals of this study is to stimulate a treatment of race as visual form, at once aesthetically and commercially effective, and not just as films’ subject matter. More work certainly ought to be done in this direction to verify, articulate, and broaden the validity of my racially based intermedial hypothesis.

For instance, one could examine broader samples of films, photographs, and other visual materials, particularly with regard to racial groups I have not systematically discussed, such as Irish, Slavs, Latinos, and Asians-Americans. One could also pair picturesque characterizations with another major vector of racial identification: physiognomy. If picturesque representations kept figures in the middle ground or background, physiognomy brought them most forcibly to the foreground, into an extreme and most expressive “close-up.”

Linked to the book’s specific argument is also a methodological reframing associated with the question of modernity. I devote the Afterword to this. Motion pictures emerged at a historical juncture that did not just feature technological and industrial innovations and their impact on everyday (urban) life, but also involved transatlantic migrations, nationalist ideologies, and imperialistic formulations of racial difference, as well as their ingrained traditions of visual representation.

When examined through the lens of racialized representations and receptions, studies of early cinema may profitably complicate medium-specific textual analyses, with their penchant for closely defined time frames. A historiographical consideration of larger geopolitical occurrences, from colonialism to imperialism, nationalism to migrations, and their related scientific rationalizations (i.e. anthropology, ethnography, and urban sociology) does not abolish textual analysis. On the contrary, it reveals films’ expressive, ideological, and commercial debts to a host of other representational practices, from paintings, theater, literature, and illustrated prints to caricatures, lantern slides, and photography.

This broader approach ultimately reveals a dynamic, centuries-old network of intermedial representations which constituted the lively, and equally modern, terrain that defined an aesthetic of racial difference and which, at the turn of the twentieth century, cinema furthered, expanded, and popularized in a unique fashion.

The discipline of cinema studies has been very fond of a formulation of modernity neatly positioned at the end of the nineteenth century and fittingly coinciding with the emergence of cinema. When it comes to national and racial discourses, however, a longer dureé of the category of the Modern, one for instance adopted by the discipline of history, may expand even further the interdisciplinary heuristics of early cinema history.

Educated in philosophy in Milan and Cinema Studies in New York, Giorgio Bertellini is Assistant Professor in Screen Arts and Cultures and Romance Languages and Literatures at the University of Michigan. Author of a monograph on Bosnian director Emir Kusturica, he has published numerous essays on ideas of race, nation, and geography in film aesthetics in two dozen anthologies and in several journals. Editor and co-editor of anthologies on silent film and Italian cinema, he is currently editing Silent Italian Cinema: A Reader and working on another book on the 1920s rise to fame of Valentino and Mussolini in the US and Argentina.