America’s Army is military history of a different kind: it uses the story of the making of the all-volunteer army as a window into the history of American society over the past forty or so years.

Today’s all-volunteer military was born in crisis. It grew out of turmoil over the Vietnam War, and its first decade is a chronicle of struggle and frustration. In the wake of a war gone badly wrong, an unpopular institution wracked by internal crisis faced the challenge of recruiting large numbers of young men from a racially, culturally, and politically divided society. Despite a dreadful civilian job market and the Army’s attempts to “sell” soldiering, all signs were bad. Many of the convulsive struggles of 1970s America–over race, over the proper roles of women, over the meaning of democracy and citizenship and patriotism–also exploded within the ranks of the Army.

The overall “quality” of recruits was poor; the notion that the all-volunteer force (AVF) would draw “motivated men . . . with the higher level of technical and professional skill” necessary to operate the “complex weapons of modern war” seemed increasingly implausible. Many thought the AVF would fail; a renewed draft seemed more than possible. But in the 1980s and 1990s–a period of more limited deployments and relative peace—the volunteer force created believers both within and outside the military.

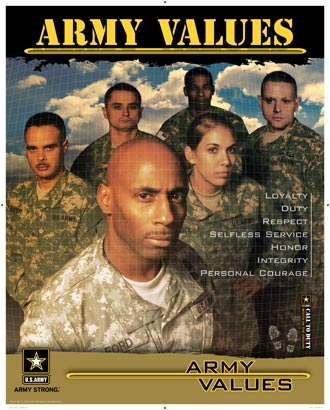

In ending conscription, the United States discarded the understanding that military service is an obligation of (male) citizenship. That move had serious implications, some of them unforeseen. All-volunteer status pushed the army into the marketplace–not only into the labor market, where it had to compete with other “employers,” but into the consumer marketplace as well. Trying to fill its ranks, the Army adopted the most sophisticated tools of consumer capitalism. It turned to market research and high-budget advertising and worked hard to portray military service not as obligation, but as opportunity.

The end of the draft also gave the military less control over who joined. The Army turned increasingly to women, accepted a vastly disproportionate number of African Americans, and worried greatly–for different reasons—about both of these decisions. I argue that the US military, out of necessity and not always happily, was the American institution that most directly confronted the impact and legacies of the nation’s struggles over civil rights and social justice.

“In ending conscription, the United States discarded the understanding that military service is an obligation of (male) citizenship. All-volunteer status pushed the army into the marketplace–not only into the labor market, where it had to compete with other ’employers,’ but into the consumer marketplace as well.”

I meant this book to change some conversations. Military history draws a lot of people who read serious non-fiction, but it occupies a complicated place in the academic discipline of history. Military history has spent a lot of time on the academic “outs,” often ignored by more mainstream US historians who have been most concerned, for decades, about the experiences and struggles of those marginalized and oppressed and quick to dismiss military history as an endorsement of war, violence, conflict, and militarism.

I’m trying to challenge that understanding and that relationship. I would insist that anyone who wants to understand the history of the United States over the past half-century must pay attention to its military. That’s not only because the military is a key instrument of US power, but because it is a critically important institution within US society.

If we want to understand struggles for social justice and questions of equality, we can’t ignore the role that the military has played–and continues to play–in these struggles. If we want to understand the meaning of citizenship, we have to think more about the ways that the rights and obligations of citizenship have been negotiated around questions of military service. If we want to engage current discussions of consumer citizenship, we can’t avoid the implications of military advertising. If we care about the shape of the modern family, the construction of military benefits are crucial. And the very creation of the AVF speaks volumes about American struggles to balance its core values of liberty and equality.

At the same time, I also believe that the army must be taken seriously on its own terms. It is not simply a site for social struggles or a reflection of ideological debates. The army has longstanding history and traditions, practices and beliefs. The significant role it plays within American society does not change the fact that its primary mission is national defense. My goal in this book was to begin to understand and explain the institution in its complexity, to show people with human motivations and powerful loyalties confronting the problems of their age, and to analyze the results of their actions.

This book was quite a change for me; my most recent (non-edited) book was on the sexual revolution (Sex in the Heartland), and I’d bet that my 1988 history of dating, From Front Porch to Back Seat, has been read more than anything else I’ve written. But as a cultural historian I’m interested in the construction of meaning, and I became fascinated, back in the late 1990s, with a series of television commercials that portrayed the army as a form of social good, picturing young men who could be seen as potentially at risk or potentially dangerous, depending on the position of the viewer, and presenting army service as redemption and salvation.

I began with a desire to study the ways the army attempted to shape its public image through commercial advertising—and soon understood that such an approach would yield a very shallow book. So I threw myself into the study of army institutional history and recruiting statistics and policy debates and arguments about doctrine and training, never, despite it all, losing hope that I could transcend the deadeningly bureaucratic language of the documents that eventually stacked thirteen feet high. I had no idea, in the beginning, that this project would require me to learn so very much about the army, but I’m very glad it did.

If someone began thumbing randomly through this book, I’d hope that it would fall open to page 168–not because that’s where I make a particularly powerful point or lay out my argument, but because it was so much fun to write. It comes near the end of a chapter titled “If you like Ms., You’ll Love Pvt.” (taken from a late 1970s recruiting ad). In this chapter, I argue that the labor-market model essentially created a structural imperative to increase the number of women in the Army, most particularly in “nontraditional” military occupational specialties (MOSs).

But commanders and policy makers, in their attempts to attract women volunteers, relied heavily on lessons learned during World War II, when women servicemembers were frequently portrayed as sexually promiscuous floozies or Amazons with “unnatural” interests. Well into the 1970s, recruiting attempts stressed old-fashioned notions of respectability, femininity, and excellent prospects for marriage. This presented a bit of a problem: If you want to attract women who want to fix trucks, emphasizing femininity is probably not the best strategy. Pushed by personnel needs, those with authority to do so made a serious attempt to recast the portrayal of women in the army, turning to a language of women’s liberation in all its 1970s inconsistencies and complexities.

Through most of the 1970s, women’s expanding roles were supported by Congress. The Senate passed the Equal Rights Amendment with a vote of 84 to 8 in 1972, in 1975 Congress voted to open all military academies to women, and by the end of the decade—with the first women scheduled to graduate from the nation’s military academies in 1980—the House Armed Services Committee was holding hearings on the use of women in combat.

By the late 1970s, members of Congress were feeling pressure—or finding support—from a growing conservative movement that opposed government-mandated equality and argued that Americans should hold to timeless truths and traditional values that defined the differences between men and women. These hearings reflect that change. I describe the testimony of Mrs. Tottie Ellis of the Eagle Forum, who argued that women were not suited for combat because combat is “violent and dehumanizing. . . in fact, men I have known who were in combat do not even enjoy war movies.” Jeremiah Denton, co-founder of the Coalition for Decency, linked women in the military to “godless Sodom and Gomorrah poison” and psychiatrist Harold Voth testified that women’s “search for an identity and role which permits them to live out a pseudo-male identity” which had led to “social pathology” and national decline.

And if the book happened to fall open one more time, I’d root for page 236. It’s a description of the Army of One recruiting campaign and reactions to it. While criticism of the new campaign came hard and fast (“Has anyone considered,” asked one noted military sociologist, “that ‘An Army of One’ isn’t likely to scare potential enemies?”) and the slogan proved short-lived, no one seems to have understood the logic behind it. The images of Corporal Lovett running through the desert in the commercial that premiered in January 2001, along with the entire “An Army of One” campaign, were parts of an attempt at rebranding. This army wasn’t about benefits and opportunity, not about money for college or the chance to learn computer skills. This was an army of warriors in training. The army’s current emphasis on the “warrior ethos” began well before the attacks of 9/11, and it had very different origins.

“The images of Corporal Lovett running through the desert in the commercial that premiered in January 2001, along with the entire ‘An Army of One’ campaign, were parts of an attempt at rebranding. This army wasn’t about benefits and opportunity, not about money for college or the chance to learn computer skills. This was an army of warriors in training. The army’s current emphasis on the ‘warrior ethos’ began well before the attacks of 9/11, and it had very different origins.”

In the mid-1950s the majority of adult men in the United States were veterans. Today that percentage (male and female) is less than thirteen. That is in large part for a positive reason: no ground war has been fought by mass armies in recent decades. But because the all-volunteer force has long been drawn from a small and relatively self-contained portion of the American population, a huge number of Americans—including many of those most likely to buy works of serious non-fiction—have no significant contact with anyone in military and know little to nothing about it.

Some of the most important and most difficult questions we face as a nation seem to require a basic understanding of America’s military. I hope this book will give those readers a clearer understanding of the contemporary military and its recent history, knowledge that they can use to make their own arguments about the nation’s future.

I also hope, in the wake of the war in Iraq and the current escalation in Afghanistan, that this book contributes to a national discussion about what it means to fight an extended war in which a small number of men and women bear the burden of military service while most of the nation is asked no sacrifice.

In most ways, such a discussion is moot. Short of massive, total war, the United States is not likely to reinstate the draft. There is little public desire; there is no political will. The military has become a powerful advocate for the volunteer force, and in practical terms most analysts agree that a volunteer force provides best for the defense of the nation. Perhaps the reinstitution of the draft (a lottery system with very limited exemptions?) would constrain American military adventurism–but that was precisely the argument the opponents of the Vietnam War made for moving to a volunteer force in the first place.

None of the answers are easy, but the moral complexities need to be acknowledged and debated. In the end, I argue, an institution that once seemed mired in crisis has achieved remarkable successes, both as purveyor of military force and as provider of social good. Nevertheless, in a democratic nation, there is something lost when individual liberty is valued over all and the rights and benefits of citizenship become less closely linked to its duties and obligations.

Beth Bailey, professor of history at Temple University, is a social/cultural historian of the 20th century United States. Besides America’s Army, featured in her Rorotoko book interview, Bailey is the author of From Front Porch to Back Seat: Courtship in 20th Century America, The First Strange Place: Race and Sex in World War II Hawaii (with David Farber), and Sex in the Heartland, and also co-author of the American history survey text, A People and a Nation. Her research has been supported by fellowships from the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Studies, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the American Council of Learned Societies.