Performing South Africa’s Truth Commission is about the messy, uncertain process of transition from authoritarian to democratic rule, and the quasi-judicial ritual that South Africa used to help accomplish such a transition. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was an attempt to draw a line in the sand, to say, “that was then, this is now.” The TRC tried to separate the massive atrocities and gross violations of human rights so routinely perpetrated during forty years of apartheid from the country’s new dispensation post 1994—a multi-racial democracy with one of the most progressive constitutions in the world.

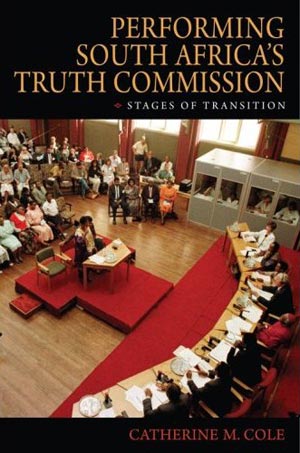

This is the first book to examine a unique and defining feature of South Africa’s TRC: its public iteration in front of audiences. Prior to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which began in 1996, there had been sixteen other truth commissions in the world, in places ranging from Uganda to Argentina. Yet South Africa’s truth commission had the distinction of being the first to transpire overtly in the public eye. Hearings happened on raised platforms and stages throughout the country, with spectators attending in person, and radio and television broadcasts transforming the commission into a media event in which thousands participated.

How did the TRC’s performative conventions, modes of address, and expressive embodiment shape the experience for both participants and spectators? By what means did people experience the hearings? Through what levels of mediation, of telling and retelling? How did medium shape the message? How did the public storytelling—which was conveyed by witnesses, governed by commission protocols, mediated by simultaneous language interpreters, journalists, and television—influence public perceptions?

I argue that the TRC’s public enactment before an audience had a unique potency—one that its written record does not capture. When seeing the TRC as a live, affective, kinetic, sonic, and visual event that relied upon interpretation by linguists, the media, and audiences in order to reach a larger South African public, one understands the power of performance—to express both the magnitude of the TRC’s ambitions as well as the inevitability of its failure to achieve closure.

Yet a failure to achieve closure does not mean the TRC itself was a failure. A careful and nuanced analysis of the public enactment of the TRC shows that state transition can be validly and meaningfully experienced as an ongoing process with many stages.

“A failure to achieve closure does not mean the TRC itself was a failure. A careful and nuanced analysis of the public enactment of the TRC shows that state transition can be validly and meaningfully experienced as an ongoing process with many stages.”

Once at a dinner party, when I described my book as being about the performative dimensions of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, an attorney who was there quipped, “Well, that must mean you take a very dim view of the truth commission.” I responded by saying that, rather, his comment suggested he took a very dim view of performance.

Words like “theatre,” “performance,” “spectacle” and “show” are often used pejoratively when applied to politics and the law. It was precisely the conflation of theatricality and justice that made Hannah Arendt so uncomfortable with Adolph Eichmann’s trial. Justice “demands seclusion,” she said. In a similar vein, South Africa’s Inkatha Freedom Party leader Mangaqa Mncwango dismissed the TRC and its Chairperson, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, by saying, “The TRC has become a sensationalist circus of horrors presided over by a weeping clown craving for the front stage spotlight.”

In looking at the TRC through the lens of performance I neither see the commission negatively nor do I valorize it with romantic notions about the miraculous, cathartic, healing potential of performance. I simply assert that the commission was a performance—and that we need to understand how its performative dimensions operated.

The book’s point of entry is somewhat unusual. I examine several major political trials from the late 1950s and early 1960s, all of which included Nelson Mandela among the accused. While the field of transitional justice out of which the TRC arises usually focuses on state transition from authoritarian rule to democracy, I argue that we must also look at how the law is used as a performative space by a regime that is becoming totalitarian.

The apartheid state used trials to make a show—both to the people of South Africa and the world. Anti-apartheid activists also manipulated these trials, both inside and outside the courtroom, to create a counter spectacle. These early political trials were as much a part of the performative genealogy of the TRC as were both the Nuremburg and Eichmann trials and the sixteen truth commissions that preceded the TRC.

The book then examines several layers of mediation that were inherently part of the commission’s telling and performing of apartheid’s stories. To give testimony meant, inherently, to interpret and to be interpreted. This is evident in the rest of the book: I examine the language of interpreters who translated all the hearings from within a phalanx of grey booths that always lined the hearing halls, a weekly television documentary program that covered the TRC, and retrospective views of the TRC in the media and art that were produced ten years later, in 2006. I see all of these iterations as valuable and meaningful reverberations emanating from actions of atrocity that were narrated, not performed, before the TRC.

I believe that, aside from being the first book to analyze a unique and defining feature of the TRC—its public enactment—Performing South Africa’s Truth Commission is notable in a number of other regards. The book is based upon rich empirical research, including interviews I conducted with journalists, commissioners, and language interpreters; close analysis of public testimony; and a comprehensive review of TRC Special Report, an important television news program on the commission that aired weekly for two years. I assert that the “completeness” of the vision of the apartheid past, which was mandated in the commission’s authorizing act, can be discerned as vividly through in-depth analysis of performed testimony as through macro-narratives that calculate in quantitative terms apartheid’s national dimensions, which the commission’s own final report attempted to do.

My book diverges from much existing literature on the TRC: I use a humanities-based approach that moves beyond the evaluative mode. Rather than celebrating or criticizing the commission, Performing South Africa’s Truth Commission analyzes the rich archive it left behind. Regardless of one’s opinion of the commission’s efficacy, the TRC’s archive demands our analytical attention.

My last book, Ghana’s Concert Party Theatre, narrated how a particular popular theatre in Ghana, the concert party, served as a kind of living newspaper through which a largely non-literate population discussed, represented, engaged, and criticized changes wrought by colonialism and the early years of independence.

Performing South Africa’s Truth Commission represented for me a radical shift of geographic focus from west to southern Africa. The project was also a shift because rather than studying theatre per se, I used theories from performance studies to analyze something that wasn’t framed as theatre or art. What connects these two projects is a consistent focus on how performance has served as a potent and complex forum for negotiating rapid cultural, political and social changes on the African continent in the 20th and 21st centuries.

While most of my book is about the TRC as performance rather than artistic performances about the TRC, the final chapter returns to the aesthetic realm by examining Philip Miller’s REwind: A Cantata for Voice, Tape and Testimony. The controversy and production challenges surrounding the REwind cantata are quite revealing of contemporary South African ambivalence about the past, and how the work of the TRC remains both unresolved and ongoing. The composer immersed himself in the raw archival material from the hearings, especially the sound recordings. What emerges is the potency of performance, the nuance of meaning in a hesitation, an inflection, in the grain of the voice.

The cantata provided yet another iteration of those TRC stories that were performed and embodied, and like the hearings themselves, it relied upon the presence of an audience to receive and be part of the process. Ultimately it is this encounter between speaker and audience that most expresses what made the commission so extraordinary: it demanded face-to-face encounters between witness and audience, an apt format for expressing the Zulu notion of ubuntu upon which the TRC is based. “A person is a person through other people” says ubuntu, and it is through performance that such a concept is fully realized.

“Performance has served as a potent and complex forum for negotiating rapid cultural, political and social changes on the African continent in the 20th and 21st centuries.”

By viewing the TRC as performance we can see the potential for such forums as truth commissions to dramatize the complexity of the present’s relationship with the past, especially in places that have experienced massive, state-sponsored violations of human rights. Performance can provide a necessary corrective to the often-narrow epistemologies that often govern such bodies in terms of statement-taking protocols, investigative and corroborative processes, and published findings.

The next set of questions Performing South Africa’s Truth Commission raises is how much we can generalize South Africa’s experience to other forums of transitional justice elsewhere in the world. A performative public truth commission made sense for South Africa, both because of the country’s history of spectacular political trials during the early years of apartheid, and because of the unique constellation of performers who brought South Africa’s TRC into being: the charisma and showmanship of key interlocutors such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and the way South Africa as a multi-lingual state necessitated the prominence of language interpreters who were, essentially, the first actors to re-perform testimony. But how does the TRC’s embrace of public performance translate elsewhere in the world? Does South Africa provide a model that can be replicated elsewhere? If so, how? If not, why not? This is where I hope other scholars will take up and extend my work by applying it to other geographic locations.

When I first started research in 2002, my topic was decidedly politically incorrect in South Africa. One of my hopes is that this book might be part of a fresh reconsideration of the TRC by South Africans, one that moves beyond a narrowly evaluative mode. While outside the country the TRC is generally celebrated as a great success, South Africans are profoundly ambivalent about their experience with transitional justice. The TRC is seen as being emblematic of the morally and politically problematic compromises that brought about a new dispensation as well as of the failures and disappointments of the post-apartheid era.

Whether we think of the TRC was a success or failure, the TRC did put into the public record an extraordinary amount of testimony and information from people who had long been excluded from representation at all. So I think the commission deserves reconsideration as an archive, as a repository that tells us much beyond what the commission’s narrow mandate was meant to achieve.

I also hope this book will lead to a revaluation of the TRC’s rich audio-visual archive. This record is dense, evocative, and voluminous, but also neglected and imperiled. The analogue audio and VHS tapes are now quite old and fragile. They document what may well prove to be one of the richest records of the TRC’s complex cultural work. Ironically it is artists—not scholars—who have recognized this archive’s importance.

Catherine Cole is a Professor in the Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of Ghana’s Concert Party Theatre, co-editor of the book Africa After Gender?, and editor of the journal Theatre Survey. Her dance theater piece Five Foot Feat, created in collaboration with Christopher Pilafian, toured North America from 2002 to 2005. She has published numerous chapters in edited volumes as well as articles in such journals as Africa, Critical Inquiry, Disability Studies Quarterly, Research in African Literatures, Theatre, Theatre Journal, and The Drama Review.