The narcissistic present forever seeks itself in the past. Though the living try to winnow meaning from the chaos of history, they often discover only themselves among the dead generations. But in a world where extinction, not survival, is the rule, the history of failed possibilities and forsaken paths dwarfs the stingy determinism of the linear past. My book is about lost and forgotten things.

Among the casualties of history is an extinct species of professional bureaucrat called the “cameralist.” There’s nothing sexy about eighteenth-century German bureaucrats, but in their day these self-appointed scientists of the state imagined that they were in the vanguard of history. The Disordered Police State is about them.

Most people today, even in Germany, have never heard of cameralists, but they were a big deal once, members of a budding professional class, like doctors and lawyers. Universities, catering to these new administrative professionals, hired professors, who in turn developed elaborate curriculums to train them. The textbooks, lectures and treatises that these professors wrote have come to be known as the “cameral sciences.” The books published by cameralists—and there are thousands of them—rest largely forgotten on the shelves of German libraries. That does not mean, however, that these sciences of state have been without effect. On the contrary, they have served to sustain some of our most robust narratives about science, state building, and modernity. Scientific administrators, rationalizing and bureaucratizing the backward lands of central Europe, appear in our histories as the shock troops of modernity.

The Disordered Police State cuts against the grain of these histories. In it I argue that we cannot take the sciences of state at face value, because they often served as fiscal propaganda for treasuries and governments. Cameralists, on the hunt for salaries and positions, served as public relations men for the territories in which they lived and worked. Their writings painted rosy pictures of princes dedicated to the common good; but behind closed doors, in the secret spaces of princely chambers, they dedicated themselves to fleecing the people.

In the guts of the book I demonstrate how it all worked, tracking my protagonists through the fields, forests, mines and universities of early modern Germany. I examine what they published, and I compare it to what they did. In case after case, scientific administrators wrote one thing and did another. They wrote about the general welfare while defrauding the state; they published on scientific agriculture while mismanaging farms; and they painted beautiful pictures of well-ordered police states even as they benefited from a disordered world. We have mostly taken their writings at face value, as if their “descriptive” and “practical” sciences reflected actually existing things. By questioning the status of these sources, my book suggests that many of our histories about state and science in the Enlightenment have been built on rotten foundations.

“Though the living try to winnow meaning from the chaos of history, they often discover only themselves among the dead generations.”

I was trained in the history of science, a field much concerned with the relationship between discourse and practice. This influenced the course of my research, which was driven by one simple question: what did these scientific administrators actually do, and how did it relate to what they published?

It is common knowledge that some of the most prominent cameralists had careers as state officials. Historians, political scientists and sociologists have thus mostly assumed that the sciences of state reflected administrative practice. But hardly anybody has bothered to check on that. So I spent years traipsing through Germany and pawing through local archives.

What I discovered was surprising: the secret discourse of the treasury contradicted the public discourse of state administration. In other words, scientific administrators said vastly different things in secret than they did in public. Many of their published writings were meant not to rationalize the state, but to make the prince and his government look good.

So who cares if a group of largely forgotten author-administrators misled the public once? I care because our larger narratives about science, economic development, and the Enlightenment rest on the foundation of stories like this one. It may be, for example, that a certain scientific culture, incubated in the European Enlightenment, helped spark the Industrial Revolution. But I don’t believe it, because the sources are suspect.

Admittedly, it can be daunting to revisit the sources: there are a lot of them, and they can be very dull. Faced by walls of obscure history books at the library, or forced to listen to some interminable lecture about agricultural improvements in early modern Bavaria, it is tempting to leave all of this to the “experts,” those with the time, patience and knowledge to sift through the material. This assumes however that history books, neutral and objective, simply regurgitate the distilled contents of the past. We should not conflate monotony with neutrality.

William James once joked that modern experimental psychology could only have arisen in Germany, a place whose inhabitants were incapable of being bored. You could say the same thing about the history of state administration: perhaps only Germans could have produced the intimidating, detailed, colossal administrative histories that helped make Prussia, with its well-disciplined soldiers and anal-retentive bureaucrats, into the ideal type of a modernizing state. More recent variations, like Foucault’s celebrated riff on the disciplined bodies of Prussian infantrymen, have only served to cement that reputation.

But it is time to rethink the evidence upon which these claims rest. It seems obvious now that a powerful mix of science, technology, discipline, and bureaucracy created our particular cocktail of modernity. In fact, it seems so obvious that we routinely project this narrative back onto the past, displacing it onto histories where it does not belong. This is how imagined pasts become justifications for the present. It is the vicious circle of anachronism.

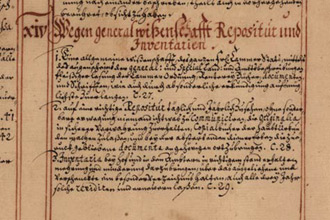

Schloss Friedenstein, the seventeenth-century palace that Ernst the Pious of Gotha built, is a good place to do research: on one side, in the east wing, the old research library; on the other side, in the west wing, the secret archive of Ernst the Pious. It is an impressive physical space. Day by day, as I ate my lunch under Pious Ernst’s statue and walked up the steep hill from town with his palace looming over me, the presence of the place—its vaults, fortifications, chambers, and halls—had an impact. I started wondering about spaces and rooms, and about the treasury; not the abstracted treasury of administrative history, or the idealized treasury of the cameral sciences, but the specific room where the duke met in council with his officials.

In the conclusion I describe a large tabular chart that I found in the Schloss Friedenstein. This “table of duties” dictated every aspect of behavior for the duke’s officials; it was hanging in Pious Ernst’s fiscal chamber when a famous cameralist named Seckendorff worked there. Initially, the chart struck me as a perfect example of early modern social discipline, a case study in Foucauldian mechanisms of control and surveillance. By subdividing space and time to provide transparency and visibility, it was a cog in the machinery of control that characterized early modern Europe.

I eventually decided that this was wrong. The table of duties was really an example of wishful thinking, because the people it aimed to discipline and control did not exist. Seckendorff’s imagined bureau had no meetings, no votes, and no timetables. He was pretty much by himself. The elaborate table of duties corresponded only to the fantasies of its author.

I focus on this episode here because it serves as a microcosm of my larger argument. Historians have been conditioned to look for certain things in archives and libraries, so that research becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. We find what we expect to find. There is no simple way out of this trap, unless you believe in the myth of the objective historian.

“It seems obvious now that a powerful mix of science, technology, discipline, and bureaucracy created our particular cocktail of modernity. In fact, it seems so obvious that we routinely project this narrative back onto the past, displacing it onto histories where it does not belong. This is how imagined pasts become justifications for the present.”

In the eighteenth century, German political economists repeatedly promised that they could harness science to improve the common good. These claims later reappeared as evidence for the connection between science and economic development during the Enlightenment. Some contemporary social scientists have even suggested that the cameralists present a “third way” for economic development, an alternative model to both Marxist and neo-liberal approaches.

The sources that historians have used to link Enlightenment science with material progress are not transparent. Professors and state officials, desperate for employment and keen for promotions, created the fiction of well-ordered police states through their regulations, books and treatises. They argued that science, properly cultivated, created prosperity for princes and their people. When these author-administrators tried to put their ideas into practice, however, the results were usually disastrous.

History is only as good as its sources, and the cameral sciences, which pretended to speak publicly about the most secret affairs of state, were deeply dishonest. We cannot trust them, and we cannot trust narratives built on them. I hope that my book adds a note of skepticism to current debates about science and economic development. We don’t know as much as we think we know.

If the history of state building and state finance is about progressive models of development, about the relentless march to us, then it makes little sense to study the petty principalities of early modern Germany, those Galapagos Islands of state building. But if we suspend our judgment about the inevitable destiny of the world’s political and economic dodos, replacing categories of hierarchy with difference, perhaps we can begin to understand what these forgotten states actually produced instead of how they failed. Release the past and you release the future.

Andre Wakefield is Associate Professor of History at Pitzer College in Claremont, California. He is the editor and translator, with Claudine Cohen, of G. W. Leibniz’s Protogaea (Chicago, 2008) and is currently working on a book about Leibniz’s misadventures in the mines of the Harz Mountains. He enjoys teaching and writing about the history of science, deep time, environmental history, political economy and world soccer. Wakefield earned his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. He lives in Claremont with his wife, Rebecca Kornbluh, his sons, Zachary and Eli, and a large black dog named Bernie.