Newlyweds on Tour is the first historical study to trace the origins and growth of the American honeymoon from 1820 to 1900. Rather than treating the honeymoon as a simple by-product of the privatization of the family, I argue that it was formed at the interstices of and helped articulate a variety of narratives -– patriotic, conjugal, sentimental, and sexual – that were central to modern American national identity.

To track these narratives, I move between primary accounts of newlywed experiences (diaries and letters) and a wide range of textual, visual and architectural representations (maps of matrimonial love, engravings from the popular press, sentimental and sensation novels, wedding night pornography, and palace hotel bridal chambers). This interdisciplinary analysis tracks the specific ways in which newlyweds on tour prompted individual and collective feelings of attachment, whether to the ideals of egalitarian marriage, domesticity, nation or sentiment itself.

Above all, I am interested in how the honeymoon helped to consummate the romance of consumption. It was the ultimate union of sentiment and commerce, a union that continues to thrive in today’s ways of wedding.

“I came to see the bridal tour as a kind of two-way frame: the honeymoon framed narratives for newlywed consumption; and newlyweds on tour, either physically or in the media, become a frame through which others consumed these narratives.”

At the root of this project lay my interest in honeymoon suites. But the more I read about the general origins of honeymooning in North America, the less it made sense. Why begin married life with a trip that’s exhausting and expensive and, usually, very public? Indeed, the honeymoon’s contradictions run deep and, from certain angles, mobile figures like “travelling brides” can seem subversive. They bring to the surface – though never resolve – many of the tensions emerging in America in the nineteenth century, for instance, between commercial and domestic cultures. Newlyweds on tour were often caught between the realities and representations of honeymoon practice.

I’d like to emphasize this last point because it will help to explain the method and sources of Newlyweds on Tour, located somewhere between social and cultural history. I started off treating this project more as a “straight” history of honeymooning. But, like most people writing about Victorian conjugality and sexuality, I soon realized that more obvious sources, like newlyweds’ letters or diaries, were anything but forthcoming about their subjects’ experiences. They were, for instance, virtually silent on the subject of the wedding night. Thus, I cast my net wider, seeking out other evidence that might testify to the honeymoon’s function and meaning.

I did not look long. I found an abundance of newlywed descriptions elsewhere. A small but steady trickle of newlywed mentions in the 1820s and 1830s became a flood by the 1850s as they became a well-established type in the American social panorama, a standard feature not only of the tour but also of its representations in a wide variety of media. The 1870s and 1880s, the golden age of the illustrated weeklies, offered a particularly rich seam of visual representations. (I analyze a number of these in the book.)

As I amassed further visual materials and samples, it became obvious that newlyweds on tour were, if anything, excessively visible in proportion to the number of them doing the tour. The only way to account for this cultural over-representation was to recognize how the tour was formed at the interstices of narratives that were important to modern American national identity – patriotic, memorial, conjugal, technological, romantic, religious, affective, and sexual narratives. And they didn’t come seamlessly together; often they did just the opposite.

I came to see the bridal tour as a kind of two-way frame: the honeymoon framed narratives for newlywed consumption; and newlyweds on tour, either physically or in the media, become a frame through which others consumed these narratives.

But how did individual experiences and these cultural representations knit together? Newlyweds were very conscious of the ideals and stereotypes of honeymooning behavior and knew full well they were on display; brides in particular were caught between the competing demands of privacy and exposure.

William Dean Howells brilliantly plays on this when the newlywed Isabel March in Their Wedding Journey confesses that her “one horror in life is an evident bride.” But very humorously Howells makes it clear that, in a society where newlyweds are widely circulated cultural currency, the stereotypes were impossible to ignore. This is not to say that newlywed behavior was pre-determined, but rather that they were always cross-referencing or negotiating their own experiences against these larger cultural scripts as they moved through the landscape of the tour.

How did these narratives operate? I suggest it was through the process of sentimental identification. The honeymoon provided a time and space in which newlyweds underwent intense bonding (itself a sentimental process) to ensure their marriage started off right. But it was also believed that honeymooning newlyweds stirred up the sentiments of the population at large. The sight of them, standing before a repertoire of iconic sites like Niagara Falls, prompted larger feelings of attachment amongst their audiences by invoking imagined similarities, (supposedly) universal feelings, and communally held values. Such feelings – the awareness of shared bonds – had real resonance in nineteenth-century America which was still in the process of imagining itself as a unified entity.

My final point, however, is that newlyweds also became symbols of the dangers of sympathy and the possibilities for it to be improperly directed or uncontrolled. Unsurprisingly, reformers and conservative commentators of all stripes disliked the promiscuous mingling of gazes and identities which sympathetic identification encouraged and worried about its projection onto material goods and things. (Nothing confirmed their fear more than the invented traditions surrounding marriage and the way in which physical objects, like the wedding ring, came to embody emotional bonds.)

They constantly attempted to shape and re-shape honeymooning practice from the 1850s on, to make it more self-consciously private. But in their assumption that the principle function of the tour was to promote emotional bonds, it remained, at heart, a sentimental practice, even if a more inwardly and domestically oriented one. And the honeymoon remains today the most sentimental of all journeys.

The fourth chapter, “Consuming: The Palace Bridal Chamber” perhaps best illustrates the larger arguments and tensions at this book’s heart.

This chapter initially grew out of my interest in honeymoon suites—I grew up in Niagara Falls. Honeymoon hotels seemed normal, if naughty, to me growing up in the 1970s. But when I moved to England to study architectural history, they became increasingly surreal. And with good reason! Honeymoon hotels are incredibly peculiar – both in the sense of being particular (dedicated honeymoon hotels in Europe are almost non-existent) and unusual in an American context (if we buy into the idea that Americans have historically been puritanical or, at least, modest in sexual matters.) So how do we account for the growth of entire resorts devoted to newlywed sex?

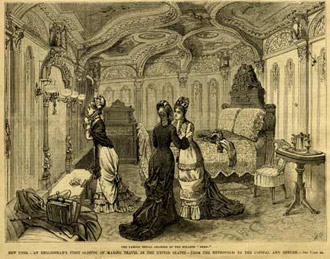

Honeymoon suites first appeared in the 1840s on Hudson River palace steamboats. From there, they were quickly adopted by palace hotels in big urban centres, particularly those constructed in New York in advance of the 1853 Crystal Palace exhibition. Honeymoon suites, then known as bridal chambers, were amazing productions: prominently positioned, lavishly decorated, and subject to endless public scrutiny. Thousands of visitors toured them physically, thanks to captain’s tours and hotel opening days, and virtually, in media articles that microscopically noted every feature from carpets to bedspreads.

While I had read my Foucault and did not subscribe to the myth of Victorian sexual repression, I was still unprepared for the sheer publicness and exuberance of these rooms. They flew in the face of the idea that the act of sexual consummation should be discrete and hidden. Rather, along with other emerging sentimental rituals like Christmas, they made it seem right and proper that significant life events be celebrated with extravagant acts of consumerism and promoted an idealized image of conjugal love in which sex and goods intermingled. The feminized appearance of the chamber also underscores that this vision of love and luxury was highly gendered. These were bridal chambers after all: their elaborately layered white interiors resembled nothing so much as a bride’s gown, and served to remind spectators of the act of bridal “unwrapping” that would later take place.

But bridal chambers didn’t simply represent the triumph of consumerism; rather, they mark a turning point in my history. The decadence of bridal chambers, along with their mirror resemblance to the upper-class brothels nearby, forced nineteenth-century social commentators to seriously weigh up the effects of America’s expanding wedding culture and its relentless focus on the bride.

They didn’t like what they saw – but sensation writers identified something even darker. In George Lippard’s The Quaker City (1845) and George Thompson’s The Bridal Chamber and Its Mysteries (1855), bridal chambers emerge as places where sentiment was faked, love deceived, and virtue lost.

For Lippard in particular, the bridal chamber confirmed the corruption of sentimentalism itself, a system which, he believed, kept women in sexual slavery. His is as powerful an indictment of romance as any made by radical feminists in the 1970s – and one suspects that the twentieth-century honeymoon suite, complete with heart-shaped whirlpool baths and Playboy-inspired décor, would not have changed his mind.

“It seems important to me that we hang on to the messiness of nineteenth-century honeymoon practice and that we don’t try to tidy it up too much – that is, impose an ideological coherence onto it that the practice itself never had.”

There is a growing body of scholarly literature on sentimentalism, weddings, matrimony, and the rituals/invented traditions that surround them. While I enjoy and have learned from many of these books, I am sometimes frustrated by their tendency to view practices like honeymoons simply as the repressive tools of patriarchy and capitalism.

Honeymoons certainly do represent society’s dominant values – sentimentalism, consumerism, patriotism, heterosexism etc. But to treat honeymoons as straightforward celebrations of these values is to ignore the contradictions and conflicts that dogged their practice or, more to the point, emerged through their practice. Honeymoons were shaped and re-shaped over the course of the nineteenth century.

It seems important to me that we hang on to the messiness of nineteenth-century honeymoon practice and that we don’t try to tidy it up too much – that is, impose an ideological coherence onto it that the practice itself never had.

Otherwise we would wrongly suggest that the “triumph” of the lavish white wedding was historically inevitable (hence irreversible) and that it always means the same thing to all its participants and its audiences. It also leaves us poorly equipped to explain contemporary Niagara Falls’s newfound popularity as a site for gay weddingmoons. As this example proves, practices like honeymooning can serve as vehicles through which non-dominant groups make claims to social legitimacy and belonging.

Although I still feel ambivalent about many aspects of white weddings (their cost, their wastefulness, their symbolic exchange of women), their very openness to appropriation – their ability to undermine those values they seem to so obviously represent – seems like a valuable and positive takeaway from their history.

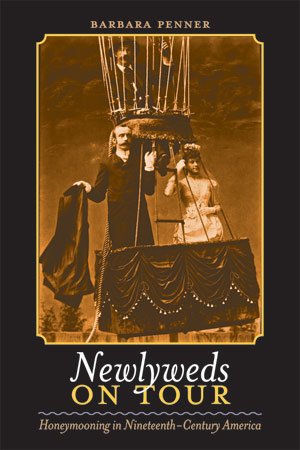

Barbara Penner is Senior Lecturer in Architectural History at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL. Her work consists of interdisciplinary investigations of the intersections between public space, architecture and private lives. She is author of Newlyweds on Tour: Honeymooning in Nineteenth-Century America (UPNE, 2009) and is co-editor of Ladies and Gents: Public Toilets and Gender (Temple University Press, 2009) and Gender Space Architecture (Routledge, 2000). Her essays can be found in the Journal of International Women’s Studies (June 2005), Negotiating Domesticity (Routledge, 2005), Winterthur Portfolio (Spring 2004), and Architecture and Tourism: Perception, Performance and Place (Berg, 2004).