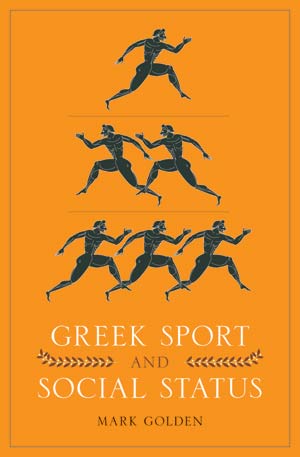

My book examines how Greek sport, the Olympics above all, has been used to attain and affirm social status from ancient times until today. This involves more than simply coveting and claiming the rewards of victory. Elite horsemen and athletes devalued or ignored the help they got from charioteers, jockeys and trainers. Women used chariot successes to rival men or boast of besting other women. Greek gladiators, slaves though they generally were, identified themselves as athletes. And the modern Olympic movement takes every opportunity to stress its connections with the ancient games.

In all this, promoting prestige has been more important than truthfulness or accuracy. As a result, our understanding of Greek sport—and of the modern movements which wish to be linked to it—is often wrong. One instance: we tend to oppose the idealized Greeks to the brutal Romans. Yet gladiatorial combat has as much right to be considered sport as the ancient Olympics.

“Greek sport provided a field for the development and display of divisions among groups as well as among individuals. Sport further ordered these into hierarchies. Because of their involvement in regularly-scheduled and recurrent athletic festivals, Greeks ranked above foreigners (‘barbarians’), men above women, the free above slaves.”

My earliest publications, on childhood in ancient Greece, grew out of my involvement with the movement to force the University of Toronto to provide day-care for the children of its students and the surrounding community. (We took over two buildings, one for nine months; the university eventually saw things our way.)

At the time, most accounts of parent-child relations in ancient Greece and Rome were influenced by a kind of demographic determinism. Ancient families, it was argued, lost so many babies and young children that they simply could not afford to invest much emotion in them. On the contrary: I thought Greek and Roman parents were well aware of the risks their children faced and did everything they could to help them survive nonetheless. When they failed—as they too often did—they were sustained by ritualized mourning practices and by the knowledge that many of their kinfolk, friends, and neighbors had suffered similarly. Our contemporary unwillingness to take responsibility for others’ children—exemplified by the university’s reluctance to provide day-care—made it hard for scholars to understand how individuals’ grief might be shared and so made more bearable.

My more recent work—this is my third book on ancient Greek and Roman sport—came about much more accidentally. I inherited a course on Greek sport, an unfamiliar subject for me, from a real expert, Don Kyle. Mastering the material and trying to find something to say that Don hadn’t pushed me in directions I never knew existed. Greek Sport and Social Status is in many ways a continuation of my earlier book, Sport and Society in Ancient Greece (1998). There, I identified a discourse of difference: Greek sport provided a field for the development and display of divisions among groups as well as among individuals. Sport further ordered these into hierarchies. Because of their involvement in regularly-scheduled and recurrent athletic festivals, Greeks ranked above foreigners (“barbarians”), men above women, the free above slaves.

Naturally, winners were always superior to losers, and the Greeks rarely distinguished second or third place from other also-rans. My new book extends this analysis into other eras—the Hellenistic, Roman and modern periods—and unexplored areas like gladiatorial combat. Alexander’s successors proved to be motivated much like the kings and tyrants of the archaic and classical periods (especially in their exploitation of equestrian success) and the elite of the eastern Roman Empire staged gladiatorial spectacles for the same reasons their ancestors presided over athletic festivals. In both cases, references to the past added value to present-day triumphs. The modern Olympics play up their (often imaginary) echoes of the ancient games for the same purpose.

My ideal reader would begin reading at the end of the book. (Maybe I ought to have written it in Hebrew.) The final chapter explores the ways the modern Olympic movement and its boosters seek to enhance its status by invoking the traditions of the ancient Olympics. In fact, many of the elements of the Olympics often alleged to have Greek roots—the motto, the torch relay, the marathon—were never a part of the Greek festival. More surprisingly: the modern Olympics were revived—successfully—by Greek and English movements long before Baron Pierre de Coubertin’s first Athens Olympics of 1896. Coubertin’s version caught on because he had the support of an international elite who shared his vision of competition among amateurs—those wealthy enough to train and travel without the hope of a material reward. This vision too was based on and justified by Greek practices. But Coubertin and the others got it wrong.

The Greeks had no notion of amateurism. Though Olympic winners took home symbolic prizes only, they were generously rewarded—by law—on their return. And nothing prevented them from entering any of the very numerous Greek festivals which did offer prizes of value, the equivalents of the purses in golf tournaments today. The irony is that today’s Olympics, with their competitions between professionals and their cash bonuses for medalists, are closer to the Greek games than Coubertin’s were.

“Many of the elements of the Olymics often alleged to have Greek roots—the motto, the torch relay, the marathon—were never a part of the Greek festival.”

I hope that my book will persuade people to rethink how they use the past for the present’s purposes. Take the Olympic truce campaign: no one could quarrel with its aims, to put a stop to war during the Olympic games. But the original proposal was based on a misunderstanding about the ancient Olympic truce. This was not a cease-fire, merely a guarantee of safe passage for athletes and spectators on their way to Olympia, and the Greek sponsors and United Nations supporters of the campaign no longer foster this myth. However, the Olympic truce campaign has still had virtually no success. It would be better to model a modern Olympic peace movement on actual ancient practices: for example, those who broke the truce could be—and were—excluded from subsequent Olympic festivals. This tactic has been used effectively in the modern Olympics too: some belligerents—on the losing sides—were kept out of the games after both the First and Second World War.

Or perhaps we should not limit ourselves to what the Greeks did. Some modern problems, war certainly among them, challenge us to express our own creativity and courage. This is a kind of competition the Greeks themselves would admire.

Mark Golden has taught Classics at the University of Winnipeg since 1982. He is the author of Children and Childhood in Classical Athens (1990) as well as of three books on Greek and Roman sport and, with Peter Toohey, the editor of three books on ancient social history.